Iberia: from Scourge of Islam to Launchpad of Conquest (part 2)

From reconquest to conquest

Note: This is part 2 of a series. You can read part 1 here.

Three storied European peninsulas jut southward into the Mediterranean: the Balkan, the Italian and the Iberian. They share broad similarities, like all being bifurcated between regions subject to a Mediterranean climate and zones with a more continental regime (Iberia meanwhile also has an Atlantic maritime fringe), and historically they have exhibited a recurrent pattern whereby social, cultural and historical forces proceeded from east to west. Greece goes first, Iberia last.

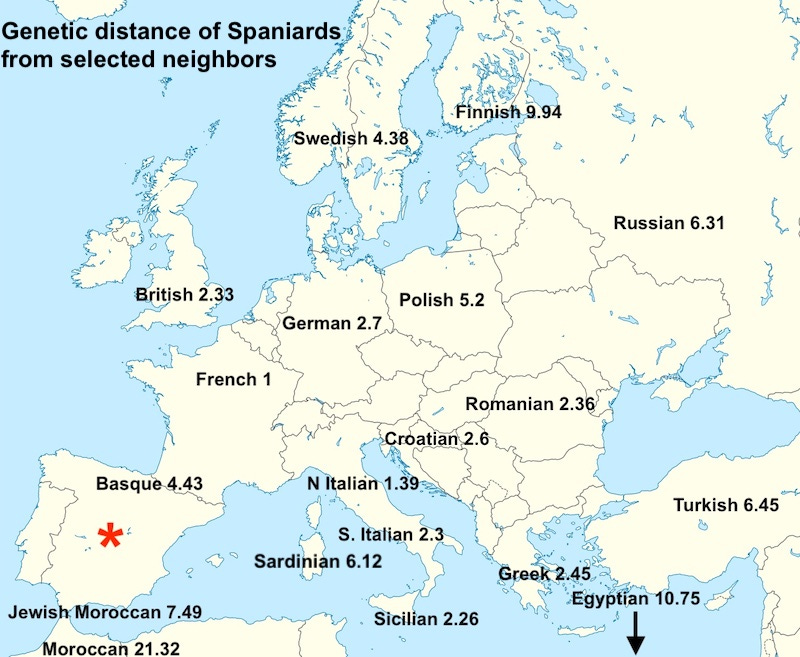

The connections between these peninsulas are also clear in terms of genetics. The map above shows genetic distances between Spaniards and a selection of their neighbors, standardized with the shortest distance set to 1 (these are population pairwise Fst values between 18 populations with 673 total individuals on 181,000 SNPs). When observing the differences between a large representative sample of Spaniards, the proximity to Italians and Greeks stands out. Sardinians and Basques, isolated from cosmopolitan currents, are at a remove. Meanwhile, due to the Muslim-era influx of Sub-Saharan African ancestry into Morocco, across the Strait of Gibraltar, the region has an incredibly steep genetic gradient (the average North African is about 10-20% Sub-Saharan African). But even Moroccan Jews, who are of partial Iberian origin and lack ancestry from south of the Sahara, are quite distinct from Iberians proper (all Moroccan Jews do have a small proportion of Berber ancestry).

Meanwhile, my assumption is that the shortest distance being to the French perhaps reflects the massive Spanish (and Italian) immigration to France since the 19th century, while the close relationship to the British is a function of both Neolithic and Bronze-Age connections along the Atlantic coast. That is Iberia’s great geographic differentiator; whereas Italy and Greece are purely Mediterranean societies, Iberians meaningfully face the ocean where Europe juts westward. But Iberia, as a cul de sac at the end of the continent, still has many connections ethnically with other regions, having repeatedly been the final destination for various tribes on the move from all ends of Europe. And unsurprisingly, within Europe, from the Iberian perspective the genetic distance increases as one moves north and east. The Spaniard and the Finn regard each other from the far corners of a yawning divide.

We know that agriculture is one of the forces that came to both Iberia, and Italy, on a westward trajectory, as Anatolian farmers first colonized Greece (agriculture’s actual vector, migration, is the reason behind the precise genetic pattern above). Thousands of years later, the emergence of complex literate societies exhibited a stepwise east-to-west pattern as well, first Greece, then Italy and finally Iberia. And in this case, stimulus from the east was essential and direct through trade and colonization.

In the 6th century BC, the first inscriptions in Iberian languages begin to appear on coins, lead plaques, stone steles and mosaics, in clear imitation of the Phoenician alphabet. And so the historical period finally dawns on the peninsula. But the light remains dim and the picture murky because the textual corpus of the Iberian languages over five centuries is thin, comprising little beyond public declarations, currency denominations and mercantile accounting. No Iberian Herodotus or Thuycidides set down a narrative history of their people. Iberia’s early recorded history was shaped by the perceptions and concerns of the Greek and the Phoenecian, who saw it as a land on the edge of the known world, with exotic, foreign and alien connotations, and most importantly, mineral wealth. Greek mythology offers allusions, with the Strait of Gibraltar being named the Pillars of Hercules because of the hero’s adventures in the far west retrieving cattle. For the ancient Hebrews too, Iberia was the edge of the known world, and it was to the antipodes of the Mediterranean that the kingdom of Israel and Judah would send their representatives to retrieve luxuries worthy of the power and wealth of their nation.

The Hebrew Bible includes eighteen references to a land named Tarshish, where King Solomon’s traders found a “multitude of all kind of riches; with silver, iron, tin, and lead…” Tarshish was the Bronze-Age southern Iberian city facing the Atlantic that the Greeks knew as Tartessos, where Herodotus tells of a king called Arganthonios, whose name derives from the metal silver. Tarshish was repeatedly associated in the Bible with ships, indicating its remove from the Eastern Mediterranean, and its connection to trade. The reality is that the narrative history of the Iberian peninsula before the second-century-BC Roman conquests is shadowy, the glimmers we gather narrowly fixated upon its mineral wealth. This outsider’s-eye view is provided by Phoenicians and Greeks alike, who established colonies on the southern and eastern coasts beginning around 800 BC. Though the genetic impact of these eastern settlers was minimal at best, they were the ones who pulled back the ethnolinguistic veil shrouding the whole period before 600 BC, recording their observations of the natives and transmitting the concept of the alphabet so that the Iberians could then author their own story.