I wanna be like you

What we talk about when we compare chimps to humans genetically

Humans are both fascinated and horrified by chimpanzees. Although I can’t personally vouch for chimps, I suspect that when we look each other in the eye, humans aren’t the only ones with an eerie sense of seeing both a reflection of ourselves and an alien distortion of our species’ familiar features. Our ape relatives offer an irresistible invitation to contemplate our kinship to the animal world. Their physical resemblance is why chimpanzee cannibalism seems to disturb us more than this sort of brutality in its many other manifestations throughout the animal world.

Because of this apparent evolutionary proximity to humans, the utilitarian philosopher Peter Singer has been making the case for extending human rights to chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans for over three decades. Singer outlined his argument in 1993’s The Great Ape Project: Equality Beyond Humanity. The reaction was generally positive, with Carl Sagan pointing out that we “share over 99% of our active genes with chimpanzees and gorillas…It challenges us to reassess many of our ethical assumptions.”

You’ve probably come across Sagan’s statistic before, usually stated in a form like: humans share 98 to 99 percent of our genes with chimpanzees. But where does this oft-repeated number come from? And how could Sagan confidently assert it when writing his review seven years before the first draft of the human genome was even completed in 2000? Is it even accurate?

First, yes, it’s close enough to correct to account for its persistence in public discourse. Second, it originated in the 1970’s using very primitive molecular biological techniques. Third, geneticists didn’t even know how many genes either chimpanzees or humans had at that time. The first results were partially simply lucky to get so close with so little data.

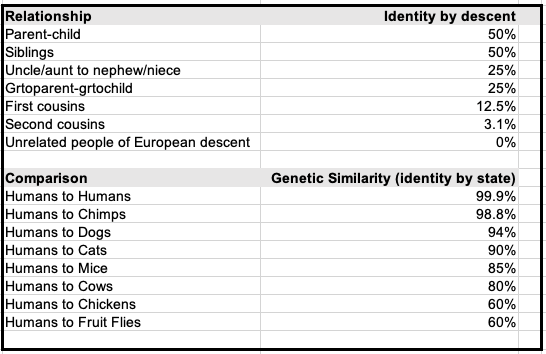

Perhaps one of the most mystifying questions though, is how does it make sense to simultaneously say you are 99% identical to a chimpanzee and that you are exactly 50% related to your parents or roughly 50% related to your siblings? It’s a good question. And I have an honest answer. But we’ll get to that. All in good time.

Better estimation through chemistry

In genetics’ “Dark Ages,” by which I mean before 1950, researchers tracked patterns of inheritance in populations via breeding experiments or observations in nature. They saw traits and assigned presumptive genes to them, laboriously noting the correlations in inheritance patterns of characteristics to infer how far apart they were on the “genetic map.” Then, DNA’s discovery triggered a revolution in our ability to track genetic inheritance. Researchers began to use properties and patterns of biomolecules to assay the underlying genetic variation which had previously only been inferred through external characteristics.

A significant catalyst for the methodological revolution was Francis Crick’s “Central Dogma of Molecular Biology,” first articulated in 1958: DNA transcribes to RNA which translates to proteins. Proteins are the building blocks of organisms, so the characteristics that geneticists were tracking earlier were often the product of protein variation. By the 1960’s geneticists were directly assessing protein variation to investigate all sorts of interesting evolutionary questions with more precision and rigor.

Though they didn’t hesitate to apply their new tools to their beloved model organism Drosophila, “fruit flies,” geneticists also immediately began to tackle human ancestry. Anthropological genetics began to train the new techniques on previously intractable questions of how closely related we were to our presumed nearest kin, the great apes, and how they were related to each other. A 1975 paper by Mary-Claire King and Allan Wilson estimated chimpanzee-human differences using two methods. They looked directly at the protein sequences of the two species, and they creatively applied existing immunological methods to assess how “reactive” extracted serums were to each other via measurements of antibody concentrations. When comparing human and chimpanzee protein sequences, King and Wilson had 44 genes available as their data set. More than four decades later we know that human and chimpanzee genomes both have nearly 20,000 genes and that only about 1% of the genome even codes for proteins. Despite their more primitive techniques, the sequencing and immunological methods King and Wilson used converged on a chimpanzee-human similarity estimate of over 99% identical.

Shortly prior, a 1972 paper had applied a creative method that mixed DNA between species to hybridize the strands and then measured the temperature at which they dissociated. The more different the two species’ strands, the less energy is required to induce them to separate. Based on these differential rates, they estimated 1.76% divergence between chimpanzees and humans. None of this went beyond indirect inference, but as it all consistently yielded values in that interval between 0.5% and 2% difference, 98.5-99% seemed like a consensus estimate.

By the end of the 1970’s, it was clear that chimpanzees and humans were near kin, closer to each other than to gorillas, and we could put some rough numbers to it. While others were exploring the primate phylogeny with molecular methods, Wilson and collaborator Vincent Sarich also combined genetic-distance estimates with molecular-clock assumptions and estimated that the human-chimpanzee divergence probably occurred 4-6 million years ago, far more recently than paleontologists at the time believed based on the interpretation of fossil evidence. Wilson and Sarich turned out to be correct, consensus tipping in their favor as paleontologists updated estimates upon discovering new fossils like Lucy.

But what about that percentage we’re focused on? How did it turn out to be roughly correct? To understand that, we need to look at what genomics has since told us about humans and chimpanzees in terms of their DNA variation and structure.

46 vs 48

Some of us are old enough to remember that for several decades, to their shame, geneticists miscounted the number of human chromosomes, with 24 pairs for a total of 48. In fact, we have just 23 pairs for a total of 46. One pair are sex chromosomes, XX in females, XY in males. The remaining 22 are autosomal chromosomes subject to conventional Mendelian inheritance patterns. Our chimp relatives do have 48 chromosomes, though. As seen in the figure above, the simple divergence occurs at our chromosome 2, a human fusion of what is preserved as two ancestral chromosomes in chimpanzees and gorillas.

Information about chromosome number and structure can be inferred from traditional genetic techniques of staining and visualization. But over the last twenty years, powerful new methods have allowed the detailed mapping of human and chimpanzee genomes at scale. Instead of comparing 44 genes, we can compare every human gene against every chimpanzee one. But this isn’t an apples-to-apples comparison. Perhaps more a matter of apples-to-quince? Chimpanzees and humans only diverged recently, but 4-6 million years is enough time for evolution to change the structure of the chimpanzee and human genomes so that you can’t always compare the sequences straightforwardly; clearly, the orders of genes and chromosomes have shifted.

Despite the biological hurdles imposed by evolutionary change, the truth is we can compare most of the genome across the two species, totaling orders of magnitude times more than the 44 precious genes King and Wilson had access to in 1975. And about 1.23% of DNA bases in the consensus human genome differ from the consensus chimp genome. About 86% of these differences are fixed differences between chimpanzees and humans. By fixed, imagine a genetic position where all chimpanzees have two copies of base A, and all humans have two copies of base T (so AA vs. TT). The other 14% of the bases with differences show variation within humans but are fixed in chimpanzees. An instance of this might look like all chimpanzees having two copies of base A (so 100% AA) but only 25% of humans carry two copies of A (so 25% AA, 50% AT and 25% TT among humans). So far so good. But this is not all the variation in the genome. Aside from mutations at specific points across three billion base pairs (A, C, G and T), there are a whole host of differences in structural variations; copy number, gene inversions, deletions and insertions. In the 1970’s, these biophysical phenomena were still poorly understood, but today we know they comprise a substantial fraction of genetic variation. About 3% of such variants differ between humans and chimpanzees.

Now, let’s return to proteins, which only 1% of the human genome codes for. When molecular evolution began as a field, the focus was on proteins because they were easier to assay than DNA, but we now know that proteins are not always the best gauge of evolutionary distance and history. This is because most proteins are strongly constrained by negative selection and evolve far slower than neutral DNA does generally (breaking a protein can prove dire, so protein-coding regions of the genome are extremely resistant to change). Human and chimpanzee protein-coding regions of the genome are about 99.1% identical, implying less than 1% of the 1% driving the physical differences. Adding structural variation, from gene duplications to deletions, to base-level mutations would yield a value closer to 95% than 98-99%. But I think the reason the 98-99% value is still in circulation is that it gets the primary qualitative result right. Humans and chimpanzees are incredibly close genetically.

So how does the chimpanzee-human difference stack up against the human-human difference? If you compare DNA-based differences between chimps and humans, that’s about 37 million positions between the two species. If you picked someone off the street and compared their genome to yours, about three million positions would be different. That’s 0.1% of the genome if you’re counting. Since siblings are genetically much closer, they differ on maybe about two million positions.

But wait, how can siblings be 50% identical but be up to 99.93% genomically identical? Genetics offers two different ways to think about the genome, identity by descent (IBD) and identity by state (IBS). Here, I’ve simply moved between the two. The latter is easy to understand because in 2022 it’s just looking at whole genome sequences and comparing the bases and other variants. Count up the similarities and differences. But identity by descent is a trickier concept.

Segments not SNPs

The above screenshot is from 23andMe, which focuses on health, traits, genealogy and ancestry. Ignoring the exact estimate of DNA shared (since they’re leaving out the sex chromosomes); you can see that I share about “half my DNA” in this method with my son. This is as you’d expect. But notice that we apparently share 22 “segments.”. What does that mean?

When 23andMe returns segment matches between two individuals, these are whole long sequences of the genome that read precisely identical. For example, my son’s chromosome 1 has one copy from me, and those 250,000,000 bases match mine almost perfectly (at the most he might have a few new mutations). If I were comparing my chromosome 1 with a random person’s, I’d expect about 250,000 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) differences breaking up the homogeneity of segment matches.

Though this is all the fruit of new technology, ultimately it’s pointing to a well-established theoretical concept called identity by descent, which means that you are tracking genetic ancestry within shallow genealogies or pedigrees. This contrasts with identity by state, which looks at the specific genetic variation irrespective of relatedness. Today identity by state means base pairs and structural variants. I am AA on rs1426654, just like 95% of Europeans. That is not because I share recent ancestry with 95% of Europeans; I don’t (assuming you don’t count 4,500 years ago as recent). It just happens that rs1426654 has been subject to natural selection across the world, and the A allele has increased in frequency. This has less to do with genealogy and more to do with adaptation. Mutation and drift are other ways you can wind up with the same genetic state at variable SNPs as someone you are unrelated to. And since we’re a young species and closely related amongst ourselves on an evolutionary time scale, most of our genomes are the same (I’m 99.9% genetically identical to my wife across my genome even though our relatedness is zero).

For identity by descent, imagine that within your recent genealogy you have tracer dye that highlights DNA segments from different ancestral individuals within the last ten generations or so. It’s a way to keep track of pieces of your genome you inherited from this or that person and also infer Mendelian processes like recombination across the generations.

Since you don’t share recent ancestors with chimpanzees, when you see a number like 98-99% identical you aren’t talking about identity by descent. You are talking about identity by state.

But what does 98 or 99% mean to us?

When geneticists initially concluded that chimpanzees and humans were 98 to 99 identical, the public was shocked because our two species look so different. Or at least that’s what we like to tell ourselves. The humans who find this statistic shocking presumably react as they do because Homo sapiens and Pan troglodytes (chimpanzees) are physically different. There are two problems with this puzzle of how a small genetic change could lead to such large differences. First, who is to say that chimpanzees and humans look that different? We know humans are evolutionarily young, but a diminutive brown-skinned Mbuti tribesman looks very different from Dirk Nowitzki, a pale, gangly, German former NBA player. And yet they share ancestry within the last 100,000 years. The time since our last common ancestor with chimpanzees is about 100 times longer than between the Mbuti tribesman and Dirk Nowitzki, so why should we be surprised that the various great apes exhibit a lot of diversity in appearance?

Second, we didn’t have many good intuitions about genetic divergence in the 1970’s. A 1983 article in The New York Times, Keeping up with the genetic revolution, stated that “Of the estimated 100,000 genes found tucked up inside a human cell, some 800 have now been tracked to their chromosomal locations, with new genes being mapped at a rate of 200 per year.” We now know there are just 19,000 genes, though at a steady rate of 200 per year it still would have taken until 2074 to map the whole genome.

Understanding that we’re about 1% different from chimpanzees was good enough to quantify the complex evolutionary relationships between ourselves and the great apes. It turns out that we are great apes too, it’s not us vs. them. Jared Diamond’s The Third Chimpanzee, written in 1987, alluded to this fact in the title, as by then it was clear humans were in the same evolutionary family as chimpanzees and bonobos, with gorillas looking in from the outside. We three are the hominins.

So what?

At the end of the day, the questions of how genetically related humans are to chimps, how long ago our lineages must have diverged, and which chromosomes have merged or otherwise become scrambled... are perhaps the very definition of trivia. Who cares? Does it matter?

Well yes, and no. And for my money, vastly more yes than no. On the “no” side, it doesn't matter whether we're 99.5% or 95% related to chimps, whether we're talking about identity by descent or identity by state. Chimps don't care. Most humans don't either. We all see our eerie resemblance whether scientists quantify it or not, whether they used a tiny complement of 44 genes decades ago to estimate it or have meticulously calculated it SNP by SNP by SNP today. We're one another's closest remaining kin and science just filled in the fine details.

On the yes side, it matters in the sense that every further detail in our evolutionary history we claw back from the obscurity of prehistory brings us that much closer to fully grasping "who we are and how we got here," in the words of one of the humans working most tirelessly on that infinite quest. But there are other ways in which it matters to me. There's little risk of overstating what a golden age of discovery in human population genetics and ancient DNA ours is. Indeed, as someone working as fast as I can here to update every worthy story of human populations and deep history as newly illuminated by genomics... I'm in far more danger of running out of lifespan than of stories of humanity rendered more fascinating by our novel insights.

So for me, it's a resounding yes, precisely how related we are to chimpanzees matters. Another sense in which It matters is that every update to the story of our species' past can follow one of only a few plotlines. You have the "no one saw that coming" discoveries, sliding in from out of nowhere and engendering whole rafts of new questions, like Denisovans. You have the dark horses almost no one bet on just a generation or two ago, like every living human being on the planet today save for Sub-Saharan African hunter-gatherers being a living repository of a few percent Neanderthal ancestry. You have the much-needed prequels with the power to recolor everything we thought we knew about our recent prehistory like the Steppe's paternal star-phylogenies. There are intriguing subplots like descendants of Finnish immigrants to America and Native Americans finding their myriad cultural affinities actually echoed in genetics thanks to their shared deep Siberian ancestry. And there are very often confirmations and refinements of our long-standing instincts and intuitions, vindications of the creative approaches pioneered by earlier generations of scientists who were haunted by the same eternal questions but denied our staggering wealth of resources. The index of chimp-human relatedness is like dense intricate plotline and back story injected into a story whose rough outline we were right to feel we already knew pretty well.

And the act of finalizing those refinements, closing each pending case by dotting every “i” and crossing every “t” brings me to perhaps the simplest reason I think it matters that science seize every possible opportunity to refine or update our consensus understanding of our species' history: because we can. Our brilliant forerunners applied such prodigious creativity and ingenuity to chipping away at these timeless questions of how we became who we are. What wouldn't they have given to have even a fraction of the investigative powers we casually summon today? It is within our grasp now to settle countless age-old questions about our deep history and to decisively illuminate some of humanity's most intriguing legends. And for my money, there's scarcely a more sacred charge. We owe it to those who came before us to tell their stories to the best of our ability. And perhaps we owe it most of all to those relentlessly curious members of our species born just a bit too early to see their greatest questions answered. We're the ones lucky enough to live in a time when all these cases can be satisfyingly closed. It's the least we can do to meticulously settle each long-standing question once and for all. Here's to you Charles, Carl, Allan, et al. I wish you could behold what we now have the power to see.

Reference: Suntsova, Maria V., and Anton A. Buzdin. "Differences between human and chimpanzee genomes and their implications in gene expression, protein functions and biochemical properties of the two species." BMC genomics 21.7 (2020): 1-12.

From the title through the posthumous shoutouts, a great piece of writing. Thanks for illuminating these percentage differences. I've hankered to understand that for a while; your explanation cleared it right up for me.

Inspiring