Happy second anniversary, Unsupervised Learning!

You can’t touch this: a quiz for the diehards

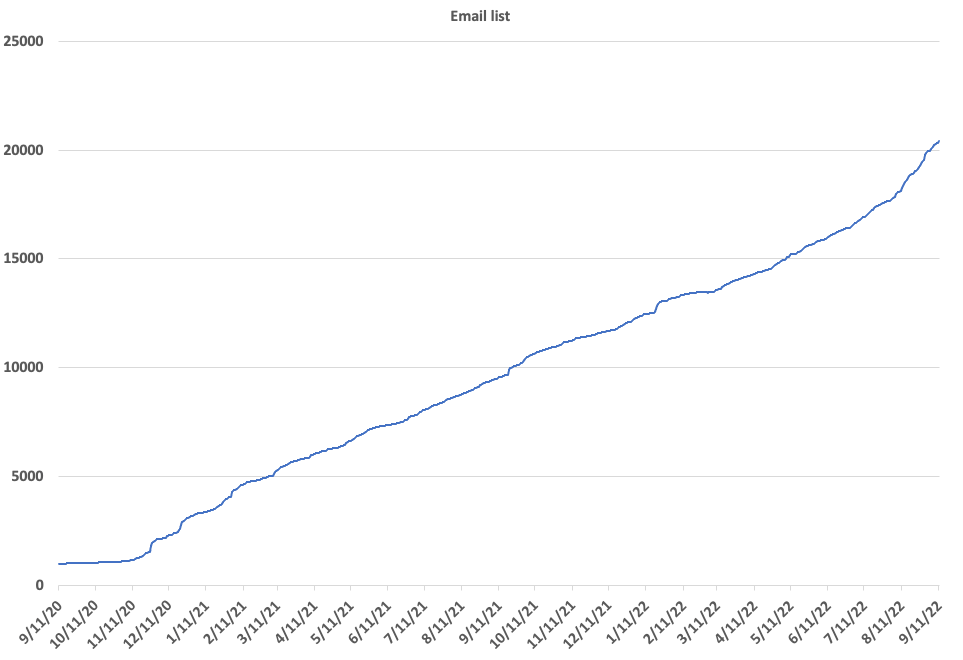

Today is the second anniversary of the Unsupervised Learning Substack. I did not choose 9/11/2020 by design. I just happened to import my little email list of 1,000 long-time followers from Mailchimp that day. I had created the list in late 2016 at the urging of a former coworker, who said “newsletters are going to be big.” I was skeptical, but six years later I have to give him credit. My email list is beyond 20,000 and grows by the day.

My interest in the Substack model was piqued by Andrew Sullivan’s resurrection of The Weekly Dish on the site in the summer of 2020. I’d admired Andrew since he was an editor at The New Republic in the early 1990’s, and came to know him a bit as a fellow blogger during the 2000’s. If Substack was good enough to lure Andrew back, I assumed it was good enough for me. Basically, by 2020 I saw “social proof” in the Substack model. Even though I created the account on 9/11/2020, I didn’t do much with it for a couple of months. It was after Matt Yglesias unleashed the content-generation tsunami that is Slow Boring that I paid attention and started thinking about what I might want this iteration of my decades of online writing to look like. Yglesias and I both have origins in the early 2000’s blogosphere. If he was going independent again, I wanted back in on whatever this reboot of blogging would look like.

More quality less quantity

Yglesias admits his “superpower” is the volume of content generation. I’m not a total slouch in this sector. As of the fall of 2020, I’d spent eighteen years writing and had published north of 15,000 posts and 20 million words on my blogs. And though I would often do the quickest reread before hitting publish, editing and reshaping the prose were never priorities. I was all about substance, immediacy and information density. Life was short; I left readability to people who were in less of a rush to inhale the entire library.

But Substack was a pivot. Starting in the last months of 2020, for the first time I chilled out on volume and suppressed my inborn compulsion to match my output to my lifelong hyperactive volume of inputs. It went against my every impatient instinct, but I began to reduce quantity with the intent of honing quality (through collaboration with a long-suffering editor).

This newfound discipline brought me a fresh audience in addition to my indulgent, long-time readers. Though the majority of my content was gated, in short order my new Substack was generating as much traffic as my blogs had in the early 2000’s. In an era of endless pieces bemoaning the advent of vapid clickbait and the collapse of in-depth journalism, I never ceased to be amazed at how hungrily thousands of readers flocked to deep, data-dense reads.

Over the past twenty years, population genetics and ancient DNA have transformed our understanding of our species’ history, rewriting everything from the deep prehistoric past to tales just a few centuries old. But all those new insights are deep in the pages of scientific journals, little accessed by the general public. Readers are often unaware that various long-standing evolutionary or historical “mysteries” have recently been definitively solved in the course of a paper or two in Science or Nature. The historically-informed updates to the tale of our species became the core of my new quality-over-quantity approach to writing.

It's always Substack, Substack, Substack

You have probably come across mainstream journalists accusing Substack of being a haven for thought-crime. The least charitable read is that this is sour grapes as they watch bolder people with more marketable talent chart their own course, while they remain tethered to a dying industry and exploitative institutions. I suppose posterity will render a more measured verdict soon enough. In the meantime, friends who know how bullish I am on this platform often privately ask whether I am confident Substack will continue to defend free speech. I am happy to say I have complete confidence that as long as the current leadership team is intact, Substack will stay true to the classical liberal vision of openness and debate. I have interacted enough with the leadership team personally and heard enough encouraging things from old friends I trust in Silicon Valley to be highly confident in this prediction.

As a technical platform, Substack is not perfect, but the team consistently invests resources and energy into improving it. And in the long run, “content is king.” Having self-hosted websites for a couple of decades now, it’s not news to me that technical glitches always require attention in ways you don’t anticipate. Over my two years using it, Substack has been progressively reducing the friction of writing on the internet. They prioritize allowing writers to write.

Given the combination of the platform and the company’s corporate values, I have consistently recommended Substack as a worthy place to write to friends whose output I value.

On day jobs and second rounds

I sat down with some of Substack's founders and core team when they were in Austin recently. One of my biggest questions was how in a climate like 2022 America even an ultra-principled team of founders can safeguard their strong free-speech commitment long-term. My core anxiety was the risk of erosion from the bottom of the company's structure upward when their runaway success entails constant growth and hiring.

As we chatted, my genomics startup came up and one founder was startled that I also work full-time. He expressed surprise that I do Substack around the edges of my day job and insisted boosterishly that "we've got to get you on Substack full-time!"

The funny thing though is that his startup had already given me exactly what I wanted: just the dose of Substack I needed and a second chance at something almost-perfect I had thought was gone forever.

My golden age

In 2005, I was in my late 20's. I worked days as a programmer at a little startup. Most evenings I had time to read and blog and I would head straight from the office to a coffee shop/wine bar and my off-hours intellectual life. It was a golden age online. My blog was a few years old and as I churned through my compulsive diet of books on history, genetics, psychology, economics and politics, the blog was where I publicly digested my prodigious recreational intake. I enjoyed brilliant fellow bloggers and a vibrant, raucous comment section that kept me honest. I interacted daily with other early figures of the science and politics blogospheres, almost all of whom today are either writing prominently, running startups or publishing prodigiously from their academic labs.

I made a pittance programming, and my blogging netted me even less (if anything), but I was genuinely fulfilled. I didn't take my work home. I read prodigiously as I always had and it didn't matter where I lived; I could read compulsively and write my reactions and syntheses in bursts of hyperfocus. And then I got to interact and argue with the most interesting people in the world about the ideas that interested me.

In later years, around my dining table, we would look back at what we had lost in the intervening decade and a half since that hopeful era when it felt like I lived the internet's promise daily. In my memory, the halcyon days were those first half dozen years of blogging, the earliest years of Twitter, when it was populated only by early adopters, those last years of the internet before smartphones. And then we would review the steady disappearance of output that required any subtlety or sustained attention span from its audience, as the long-form highlights of the early blogosphere gave way to products for ever more attenuated attention spans. The likes of Vine, Instagram, Imgur, Twitter, Facebook, Tiktok, etc. swept away the social internet I had loved. It was a depressing trend. I didn't enjoy reflecting on what we had taken for granted and then lost.

I continued blogging every year for two decades (March 2022 marked 20 years since my first post), but there were clearly years where the joy had gone out of the format for me. So honestly, two Septembers ago, when I ported over my mailing list and dumped it into this new-to-me platform, in the back of my mind, I wondered if I would end up doing much on this particular publishing platform. It frankly did feel a bit like rearranging deck chairs.

A renaissance you don’t take for granted

Fast forward less than two years, and I was getting drinks with the platform's founders. The golden-age internet of my late 20's was gone, but in its place they were busily charting a small renaissance in independent publishing and I'd been enjoying a front-row seat to the improbable second round. The thing about a renaissance versus that shiny golden age it resurrects is you take nothing for granted. This time you know how lucky you are.

Here's how lucky I am, two years into this project. I am again in the mode where I grab every moment of my free time to process the most interesting ancient-DNA papers out of the world's foremost labs, where I am hungry to digest their insights and marry those details with the outlines of human history I've been mainlining since the late 1980's. But now, in addition to publicly processing these syntheses from my two favorite fields of human inquiry purely for the love, I have an audience who enjoys these first-draft updates to human history enough to pay me to write them.

My annualized revenue on Substack has been steadily growing for two years and is many times what I was happy to make as a 20-something programmer who couldn’t wait to go read and blog for hours after work. The difference is that whereas in the golden age of blogging, I worked a 9-5 to be free to blog in my free hours, now I write a Substack in my downtime, both to support my family and to free me to work full time getting a genomics startup off the ground.

My editor often points out what a dream job I have. I have no boss. I have never had to pander to my audience. I have no corporate underwriters to tiptoe around. I don't even have any competitors. The histories I'm trying to illuminate are indisputably worth knowing and they aren't really otherwise appearing much outside my peer-reviewed primary sources.

Given the choice, I might go back to that golden age, just to savor that fleeting impression that the internet's arc bends towards depth and quality. That and my 20-something stores of energy. But in terms of personal satisfaction, it is nothing but a gift to note how out of date those gloomy dining-table conversations we were having at my house a few years ago are. Improbably, some of the golden-age blogosphere did roar back to life. And people had missed it enough to pay generously to keep it around this time.

Recently a new subscriber showed up in the comments to a paid post and enthused, Where has this Substack been all my life?

Well, a few places. In very rough draft, it has been a blog since March 2002. And in its current form, its constituent ingredients have been:

in my brain ever since I got my first public library card in 1984,

in every ancient-DNA paper coming out of the world's best labs for the past two decades, and

crucially, in this renaissance format, it has and only could have been born again on this singular platform, where it has now been growing for exactly two years.

Cheers, Substack! Thanks for a couple years of enjoyment and quality output I didn't see coming. Here's to many more for this particular Substack and every other one that ups its writer's or its readers' quality of life!

Looking ahead and looking back

The next few years will likely continue to advance our understanding of human origins, and I expect to write more on that. I go where the most interesting data and my historical interests lead me, but I think it’s safe to predict that my bread and butter on this Substack will remain genetically-informed histories of particular nations and regions, genetics explainers, plus posts delving deep into paleoanthropology.

Finally, one comment I cannot say I’ve received from my astute readers over the years is “this isn’t data-dense enough.” To be sure, I get (and welcome!) occasional complaints that an hour and a half podcast was too short and they’d have preferred my guest and I continue our abstruse meanderings for hours. But in terms of content, I’ve always had the privilege of attracting brilliant readers who realize how little we/they know. For their entertainment, I looked through thesecouple years of data-dense posts and thrown together a quiz. Give it a whirl. There’s no downside; either you retained a ton of detail or you have so much more good re/reading ahead of you!

If you take it and want to submit your email at the end or tweet your quiz results and tag me @razibkhan, I’ll do a random draw at the end of Wednesday, September 14 and pass along a free yearly subscription to the winner.

some of you have noted it's amazing what i can produce on this substack despite using time on the margins for me (eg before i go to sleep usually). two things

- the editor does a lot of work, so a lot of the writing is the editors even though the ideas/facts originate from me

- i usually do almost zero original research for the posts. all about stuff i have been reading since i was a kid. 'i write what i know' so to speak. that makes a huge difference time wise

Happy anniversary and thank you for all the work you do Razib. I did better on the quiz than I expected, most of my wrong answers came from choosing between two options rather than pure guessing. Now I know I need to review the Yamnaya/Sintasha content as well as wrap my brain around the haplotype stuff.