I chose America.

I came at five, preliterate, marching self-importantly from one Heathrow connecting gate to another, my mother trailing serenely behind me, carrying the baby and everything else. Letting me believe I was leading us to our destination.

We came to keep my dad company while he finished his PhD. He had done his Masters outside Bangladesh, too, and returned after. For the first couple of years, I knew my idyll was a temporary one. It didn’t keep me from getting attached.

Once my dad had a PhD and sponsorship, I began to hope. I became America’s most ardent booster. My parents would waffle. They never got very good at being Americans. On a good day, it was the land of opportunity and everything was better than Bangladesh. On a bad day, everything was worse. I had very little use for my parents’ conversations, save for the stay-or-go ones. Then, I hung on their every emotional hue. It is the only question on which I ever remember advocating for myself. According to my mother, I also once threatened to throw myself out an upstairs window if they didn’t buy me a bike like everyone else had. She has no concept of how much more heavily the question of whether I could have America forever hung on me at that age. It felt like life and death.

It’s hard to express how lucky it feels to be an American to someone who’s never lived in fear of it ending.

My children will never know how it feels to choose America. Half of their friends have an immigrant parent. They think everyone comes to stay. Old people asked me where I was “really from” or marveled at my perfect English. But my kids barely meet anyone who doesn’t understand that their blur of skinny tan legs pounding down the pavement, fruit of first-generation and fourth-generation immigrants who chose this country, is as American a creation as it gets. One of those uncomprehending souls accosted our little family of four in a supermarket when our son was a few days old. Oh! she said, poking her face in the newborn’s, So little! What nationality IS he?

My sleep-deprived wife was mostly annoyed that our nation is so obnoxiously bad at talking about race. But think of it, not only was he one of the planet’s newest Americans, he was something else that could probably then only happen in America. This was our only baby we managed to get even low-coverage whole-genome sequenced before birth. If she really wanted to get into his ancestry and “nationality” as she put it, I alone among parents of newborns in the world on that day, could have already told her things like that this few-days-old human had randomly come up with fully three times the Norwegian ancestry of his squishy-cheeked toddler sister standing there holding my hand.

I don’t have any illusions that other parents are as fascinated by access to this futuristic trivia as we were, but if you want to push the boundaries of knowledge, if you want to try something audacious, if you crave to know things for the sake of knowing, if you want to live in your full weirdness, you come to America. Or if you’re little like I was, you do everything in your power to stay.

Questions of human populations and ancestry have fascinated me since before I could even adequately articulate them. I first tried asking my dad’s grad-student friends at parties, but their answers were patently idiotic. They were physicists and engineers. They thought it was funny how much I wanted to know about humans. At 17, I found the work of human population-genetics giant Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza (another immigrant who chose America as backdrop for his massive contributions to human knowledge) and a whole world opened up.

Before I was 30, Linda Avey had co-founded 23andMe. I now lived in the future of my dreams. Screw Craig Venter’s three-billion-dollar genome; I immediately started fantasizing about whole-genome sequences anyone could afford. I’d survey people: Would you pay a million dollars for your WGS? Would you pay $100,000? How about $10,000? What if someday it’s like... under $1000? I’d ask melodramatically like I was asking if they’d live forever if it became possible in their lifetimes. As it turned out, I got my WGS in a flash sale for $299. Just a decade earlier I’d pinched myself that I could pay 23andMe $399 on “DNA Day” to get my million little markers read.

Now every day was DNA Day. I lived and breathed direct-to-consumer genomics. People’s results weren’t telling them enough of what they wanted to know. They’d reach out to me to tell them more. I got to help multiple friends tease family tales buried generations deep out of their surprising results. Asian adoptees and African Americans were particularly hungry for details about their roots. I started the African Ancestry Project and hundreds of strangers came to me, results in hand so I could try to tell them more about where they came from. Millions of people shared my old drive to know more about our species.

I went on to help shape ancestry products for half a dozen companies. I reviewed results before they went live for Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s Finding Your Roots series. I worked for and became friends with Linda Avey. I lived my dream.

Everywhere I went in America, people had believed me when I showed them who I was. On my first day in a new school, I was different-looking, so the boys would jump me. I’d pull off my glasses, fight back like a deranged maniac and no one would touch me again. The brown kid of Muslim parents, I showed up at the atheist club and they let me be vice president. I’ve always asked everyone I met impertinent questions, from maintenance workers to MacArthur Geniuses. Often the minute we meet. Once they get used to it, interesting people are usually down to talk about absolutely anything. I truly don’t judge. I enjoy hearing about absolutely everything. I don’t quite understand taboos. I never have. For nearly two decades, I’ve blogged whatever I felt like exploring.

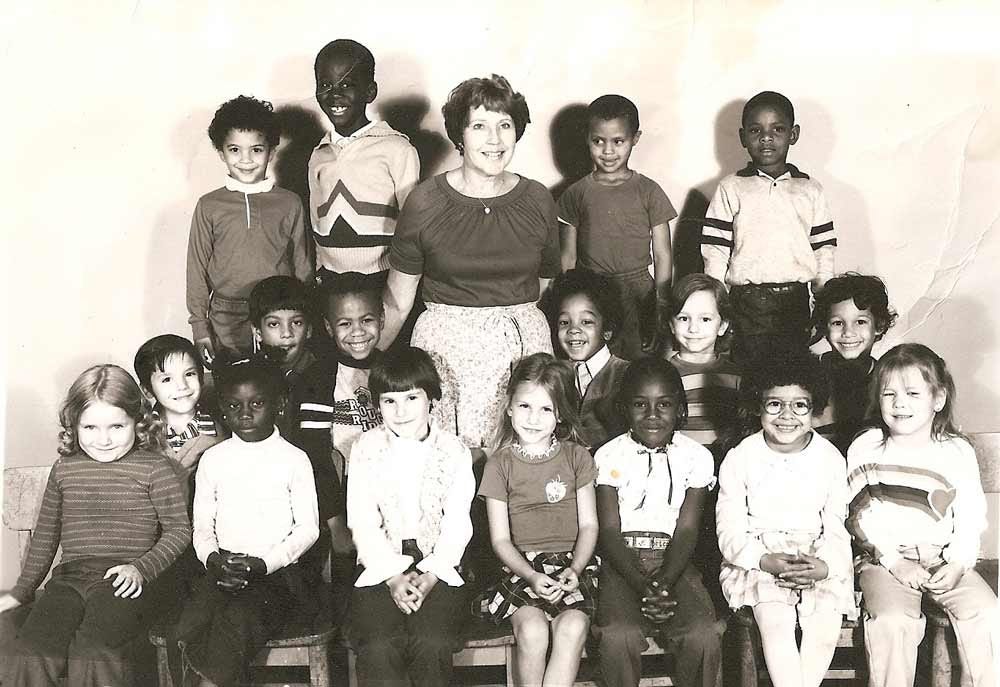

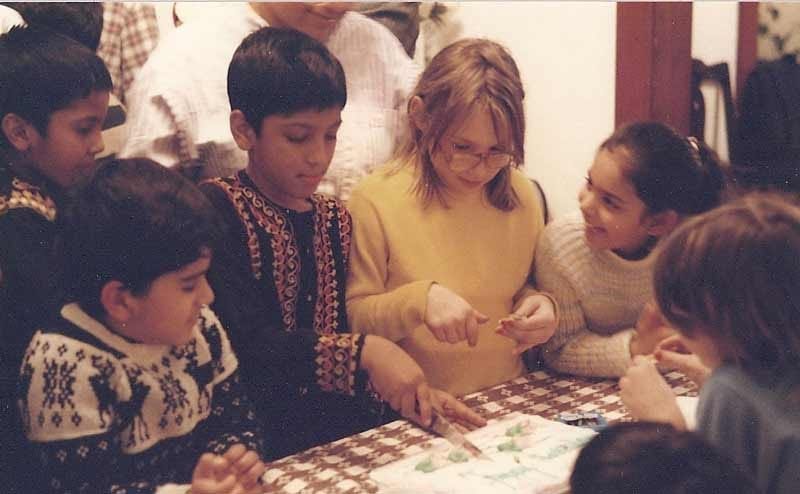

When I was going through school, as American as I was becoming, my teachers could see my parents didn’t have a clue. They’d tell them what to do. With mixed results. One told them Rajib wasn’t a good spelling. So I got a much more googleable first name. And so did my little brother, so we could still match. Another could see that I was bored and not challenged. She lobbied my harried dad until he got fed up and agreed to move me to a magnet elementary with an accelerated track. In 7th grade, my teacher trekked through the snow to try to coax me off my sickbed long enough to come qualify for the National Geographic Geo Bee. She knew my geography and demography obsessions made me a shoo-in. My mother didn’t care. I needed to recover from my Nth bout of pneumonia (It wasn’t until adulthood that I understood scratchy wool sweaters weren’t meant to be worn against the skin. God, I hated sweaters. My family never adapted to lake-effect snow.).

My lack of interest in self-censorship or taboos suited me. I grew up in a golden age for the restlessly curious. Masses of data became freely available, whether DNA data sets or General Social Survey and World Values Survey. Anything I’ve wanted to know, I could chip away at, data point by data point. Almost anyone fascinating I’ve wished to talk to, I could email. Often I’ve met them. Brilliant, curious people would join me in blogging about interesting questions, often pseudonymously, before slipping back into their high-profile career tracks. I never tried to be anonymous. I didn’t crave any renown or responsibility beyond that of always knowing more. And I was fine having my name on that. I’ve never been ashamed to be curious.

It was truly bewildering when in the middle of my PhD The New York Times asked me to join a big batch of occasional editorial contributors. I think they were trying to show they could still handle viewpoint diversity. There were some cool people, like Zeynep. But even alongside people I admire, I knew I didn’t belong on any New York Times list. The couple of op-eds I’d already written for them had been most-read pieces that week, but that’s different than an actual official affiliation. I dig into data and write things people find interesting, but I don’t toe a “party line” well.

So it seemed like an odd fit. But I went along with it. They wanted a bio. They wanted a headshot. I didn’t have time for this, but I remember googling local photographers. In the end, we decided f*** it, I put on a clean shirt, we parked the baby at the foot of a chair, and took a bunch of pictures against a wall of peeling siding before sunset. I still use one of those for my headshot some places. But not at The New York Times.

When my editor called that night to apologize for the about-face (the original line, earlier in the day was NBD, sorry about all this man, it will blow over), he said Christ, man, how did you have time to write that much? They’d thought they had vetted me. They had no idea how much an uncensored human can write and think when all he cares about is knowing more. I was 38 years old.

I have no idea what the optimal age to get canceled is. There weren’t so many of us in 2015 when it happened to me. The N is getting big enough at this point that we can probably do that survey soon. I can tell you that getting canceled for being exactly who you are, saying exactly what you think and see, and talking/writing with absolutely anyone is kind of a non-event. It’s a funny commentary on our times that one of the people they say was most rabid behind the scenes about protecting the readership of The New York Times from a dangerous mind like mine, has since joined The New York Times. Does America feel safe now, buddy?

A guy I couldn’t even place asked me to meet him for drinks recently. He was very sincere and he wanted to apologize to me for piling on on Twitter when I was canceled. I’m not going to pretend I can even begin to remember this guy. He wanted to know how to reach David Shor to apologize to him, too. Lol. You know where this is going, right? Now that he had been canceled for earnestly observing something he thought would be useful to know based on data, he realized what he had previously participated in.

Can I tell you his offense? His polling found that Democrats are alienating many voters with the relentless focus on race and social justice. With putting symbolism over substantive changes. He basically found that the party could benefit African Americans more if they chilled out on purity and virtue-signaling and drove away fewer moderates so they could actually win. Sounds like useful intel, doesn’t it? He was fired, blackballed, and had “friends” who shunned him. He’s a smart guy and he landed on his feet, but the dude had a harrowed look.

My experience couldn’t be more different. Six years on, I cannot think of a single person I value or a single place I’ve wanted to be that I no longer have access to because the New York Times deemed me beyond the pale. There are a boatload of fascinating, principled people in America and beyond who don’t care who the 21st-century New York Times thinks is pure enough. I’ve recorded podcasts with dozens of them. Thousands more give me their emails and pay me good money to tell them data-backed stories about the history of the human race on Substack.

When I was a gawky preteen, I had a promotional t-shirt that said “Get Lucky” Ask me how... from Bruegger’s Bagel Bakery. My parents, as I mentioned, have always been kind of oblivious. They had no idea my shirt was inappropriate, so I wore it everywhere. I had realized I was an atheist when I was 8. They’re on-again, off-again devout Muslims, so they took locking myself in my room to read when I was stuck at home as evidence that I was a devout, studious and shy child. Actually, I was an extremely big-mouthed blasphemer, the minute I got out of earshot of the house.

In the 2010’s, a small group of men from my parents’ homeland, which is officially secular but has a 90% Muslim population, took the bold step of blogging under their own names about themes including science, evolution, secularism and atheism. Between 2013 and 2016, responding to a call by Islamic seminary teachers, young religious fundamentalist students systematically hunted down 11 of them from a list of 80 blasphemers and hacked them to death, usually with machetes. The most prominent one, a US citizen, engineer Avijit Roy was visiting Dhaka from America with his wife when two assailants pulled them from a bicycle rickshaw. In the middle of the street, they hacked at them until Roy bled to death and his wife was badly injured. She escaped with her life, losing her husband and a finger. Roy was a few years older than me.

Other times, assailants pretended to be repairmen to gain entry to the bloggers’ apartments before hacking them to death in front of their families. I think I remember one who was fearlessly discussing atheism in a setting like a dorm. Word got out, a mob broke into the campus area, poured into the room and beat him to death while the people he’d been chatting with stood by. In another instance, the Islamic seminary teachers called a street protest against the bloggers, which escalated into a riot, killing 50 people.

Shortly before his death, Roy said this on Facebook: “I have profound interest in freethinking, skepticism, philosophy, scientific thoughts and human rights of people. I write in the internet blogs . . . and occasionally in some newspapers.”

Diction aside, me too, brother, me too. Six years later, one of us is dead and one has the privilege of watching his babies grow up taking America for granted.

I’m pretty sure I’m one of the luckiest human beings who’s ever lived. I get to look inside modern and archaic human genomes from anywhere on the planet whenever I want, something beyond my wildest futurist dreams (or his!) when I first picked up a Cavalli-Sforza book. I get to teach people about genetics, human populations and history. I can read any book or paper I choose. I think, say and write whatever I want and people even pay me to do it. I chat with some of the most interesting people alive and call many of them friends.

Ours is not the first society to plunge into a completely moronic frenzy of witch hunts and moral purity tests in an effort to vanquish some non-existent foe or avenge some imagined victim. Some frenzies of idiocy come and go fast. Some wrack a nation for a decade, kill millions, ruin the lives of millions more and require decades of recovery. Much as I love the whole grand, brutal sweep of human history, I don’t have a crystal ball any more than anyone else. Three things I will tell you with absolute certainty:

Just as in every mass idiocy of the past, the vast majority of humans keeping quiet don’t deeply believe in the “truths” we’re all supposed to pledge blind allegiance to. They’ll turn on a dime as soon as it feels safe to. Cold comfort when you’re in it, but in the long run, you can bank on this.

There’s never been a better place on earth than this one to be a “thought criminal” or get “canceled” for saying something true. To me, that’s a testament to the work of the imperfect Americans who came before us. They weren’t all fools.

I don’t know when it will end, but I’m at peace with how I’ve used my glorious gift of freedom. Are you?

Happy birthday, America. I love you. You’re the luckiest thing that ever happened to me.

Razib, this was profound.

I am not of "immigrant stock" myself, but my wife is an immigrant, who chose America. She could have easily went to the UK or Canada, but she wanted to be here - I think her mindset was similar to your father's, as she also came here for graduate school and never left.

Being African Americans, and having lived in several nations abroad in Europe and Asia, I always try to express to other black people here, that things can always improve, but life is not so bad. I have seen far worse. I have experienced far worse discrimination abroad, with zero ability to appeal to law or "moral authority" to aid me. I still had an American passport, education credentials and work experience to protect me. The worst situations were not mind, but how poor black and South Asian migrants and laborers were treated. While I was overprice ex-pat bars complaining about how I was not treated exactly like white Western expats, they were languishing in 6 people to a room in apartment made for 1 or 2 people, trying to save as much as possible to send back home, working 12 hours a day, living with no AC, etc. They would have been overjoyed to be treated like me.

Yes, but for the threat of violence, I understood exactly how my grandfather grew up clearly, and that also informed me how much had changed. After living in 5 nations outside the U.S., I can say without hesitation that there is no nation that I have been to, let alone lived in, where the standard of living and potential personal and economic growth is better for someone who looks like me.

Good work Razib. My mother emigrated from Soviet union in 1935. My father in law left Vienna in November 1938. I have always thought that any American who does feel a profound gratitude for being able to live in this country was an ignoramus and a fool.