Genghis Khan: they don’t make stars like they used to

Manspreading like the ancients: star phylogenies and the rise and fall of hyper-patriarchy

In 2003, a bombshell paper reported that one in 200 men worldwide, and 10% of Central Asian males, were direct paternal descendants of a single man who lived about 1,000 years ago. Using the then cutting-edge methods of genotyping, the researchers found that one particular widely distributed Y-chromosomal haplogroup, a set of genetic markers passed down from father to son, coalesced back to a single male some 40 generations back. The resulting genetic tree, a visualization of the descendent haplotypes, each distinguished by randomly accumulating new diagnostic mutations in the Y chromosome, arrayed itself as a “star cluster.” Instead of gradual point-by-point accumulation of new variants, the scientists found numerous descendant haplotypes separated by only a single genetic difference across their 32 markers, which produces a radiating star-shaped cluster. Visually, you suddenly get an ultra-dense node in the midst of a loosely spaced network, like a metropolis raked with arterial roads plunked down amid sparsely populated farmland. These star cluster phylogenies emerge only when a lineage undergoes massive expansion so rapidly that the customary gradual, organically emerging topology of a gene tree is completely outrun by the lineage’s pace of sudden proliferation. A one-man baby boom.

Given the populations that carry this star cluster, it is no surprise that the paper was titled The Genetic Legacy of the Mongols. In the abstract, the authors are more precise: “The lineage is carried by likely male-line descendants of Genghis Khan, and we therefore propose that it has spread by a novel form of social selection resulting from their behavior.” I might quibble with the time honored drives for world conquest and to impregnate everyone in sight actually being “novel” pursuits and “social selection” might not be the term I would choose to describe their outcomes. But I think we can all agree some uniquely successful behaviors at scale explain both Khan’s enduring fame and his astonishingly common presence among our genes a millennium later.

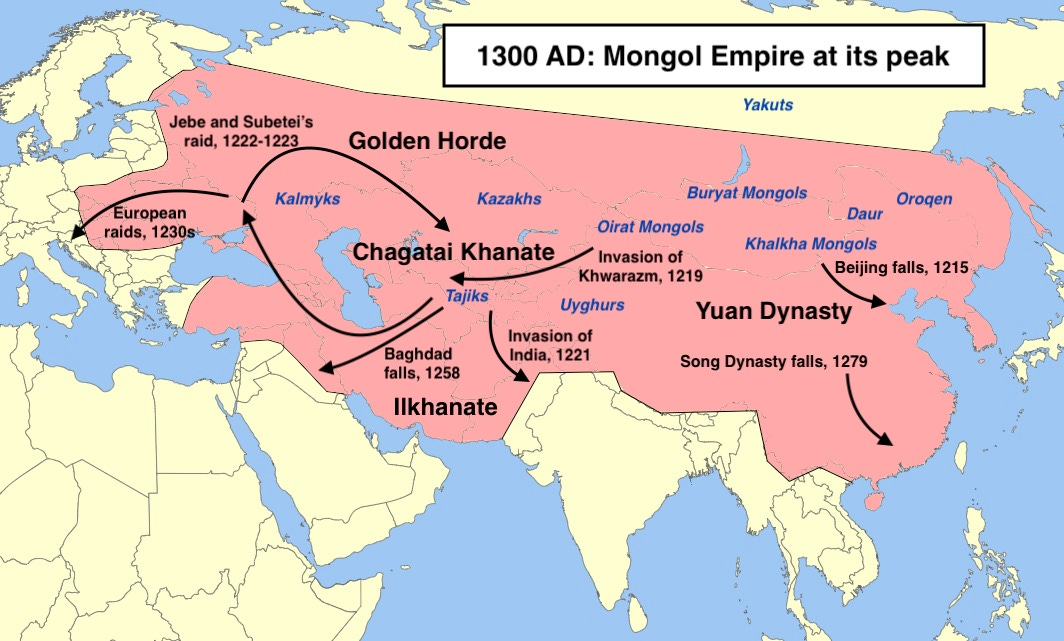

Khan had four sons by his primary wife, Jochi, Chagatai, Ögedei and Tolui. By his secondary wives and concubines, he fathered countless more. Jochi, Chagatai, Ögedei and Tolui in their turn each spawned enormous lineages. Jochi was the ancestor of the Golden Horde that would loom large in Russian history and Tolui was the father of Kublai Khan, future Emperor of China, who in turn had his own vast harem. But the fecundity of this particular lineage was not restricted to the man born Temujin, who would become Genghis Khan and to his progeny. His brothers Khasar, Khajiun, Temüge and Belgutei all fathered large broods, and Khasar’s house would repeatedly intermarry with that of the Royal Manchus who went on to conquer China in the 17th century and found the Qing Dynasty. Even more importantly, Genghis Khan was not even the first prominent ruler of his Borgijin clan; his great-grandfather Khabul Khan had ruled much of Mongolia. The clan had been founded three centuries before the time of the Mongol Empire, around 900 AD by a highly successful warlord named Bodonchar Munkhag. The 14th-century conqueror Timurlane was not a paternal descendent of Genghis Khan, which would have lent him more prestige. But his Barlas clan actually also descended from Bodonchar Munkhag, meaning he would have carried the same Y chromosome and in his turn contributed to its enduring impact.

The 2003 discovery made headlines even beyond the confines of science media, with write-ups in The New York Times and National Geographic. Since then, other star clusters that point to the existence of “super-male lineages” have been detected. A branch of haplogroup R1b has been adduced to derive from the Ui Neill, descendants of the 4th-century Irish high king Niall of the Nine Hostages. East of Mongolia, and about four centuries after Genghis Khan, the Manchu people also underwent a massive expansion with their conquest of China in the 1600’s, and there scientists observe another associated Y-chromosomal star cluster.

These particular historical instances illustrate a broader phenomenon: the periodic exponential increase of a particular Y-chromosomal lineage and its sweep across a population. The most plausible explanation is what the 2003 paper's authors posit: social selection, which likely played out via conquest, the extermination of local male elites and the rape and amassing of women in harems. Their choice of term can sound bewilderingly bloodless, but that’s kind of the point; the authors were only interested in the patterns of inheritance and what drives them. So we can think of the misleadingly anodyne “social selection” as in contrast to “genetic selection.” Human behavior alone, not functional genetic fitness swept this lineage to overnight dominance. We can see this elsewhere historically in phenomena like the Iberian expansion into the New World. The frequencies of haplogroup Q crashed overnight, replaced by haplogroup R1b. This reflects the enslavement and extermination of indigenous men across much of Central and South America, and their replacement with lineages rooted in Europe. But star clusters are perhaps at their most intriguing before recorded history. A 2015 paper reported the emergence of several star clusters around 4,000 years ago, likely associated with polygynous social structures. We may never know who these people were because these expansions occurred beyond the purview of literate civilization, but it seems clear that Genghis Khan had many prehistoric forerunners. He may in fact have been among the last of his kind, not a singular exception.

On the trail of Temujin’s Y chromosome

Since 2003, The Genetic Legacy of Mongols has been cited 694 times (median citation number is 4), and still receives coverage in popular media, like IFLScience in 2022. But science is not static, and the original paper’s exact conclusions have benefited from updates and refinements. When The Genetic Legacy of Mongols was published, the first human genome draft sequence was still just three years old. Whole-genome analyses of the Y chromosome were not feasible, and neither were dense genotype arrays like 23andMe, which samples hundreds of thousands of positions. In 2003, to type some 1,000 men across Eurasia, the authors had to content themselves with 16 highly variable microsatellite markers, and a mere 16 SNPs or single nucleotide polymorphisms (contrast this to a standard 650,000 SNPs on today’s 23andMe test). The utility of microsatellite arrays is in selectively focusing on genomic regions with lots of mutations, sequences of repeating base pairs ranging between some 10 and 100 DNA positions in length. But, the limitation of microsatellites is that they have very high and uncertain mutation rates, meaning that though they’re excellent for differentiating individuals (the very reason for their traditional role in forensic identification), they are not optimal for calibrating branch lengths on a phylogenetic tree.

More recent work from 2018 using whole genomes and ancient DNA sheds a different light on the “Genghis Khan lineage,” haplogroup C2*ST. A notable feature of the original work is the wide geographical range found for C2*ST, and the fact that it is coterminous with the known geographic range of the Mongols’ expansion in the 1200's. The Hazara people of modern Afghanistan, Shia Muslims who speak Persian, have an oral history of being descendants of Mongols who fled political turmoil in Iran. Not only do they have a high frequency of C2*ST, genomics has confirmed their broader Turco-Mongol ancestry (visible in their facial features as compared to other Afghans). But C2*ST is also prominent in populations like Kazakhs, and a branch is found among the Daur, an isolated Mongolic population of 130,000 inhabiting the upper Amur River Valley, distantly related to the Mongols proper. Additionally, genotyping actually turns up nearly half a dozen haplogroups carried by different men claiming to be Khan’s direct descendants. This is not shocking, there was some doubt as to the paternity of Khan’s oldest son, Jochi, because Khan’s wife Bortei had been kidnapped by the Merkid tribe at the time of Jochi’s conception. Even in high-status lineages there is about a 1% probability per generation of a “non-paternity” event that might break the biological chain between father and son. This means that 1,000 years down the line from a presumed common ancestor, there’s a 35% chance that a man’s Y-chromosome haplogroup won’t match his putative forefather's.