Fury out of the North: from pagan slavers to Christian kings

Heathen sea nomads, scourges of civilization

Related: After the Ice: how foragers and farmers conquered Scandinavia, Chariots of Ice, Coursers of the Sun and The 100-year-winter and the coming of Ragnarök.

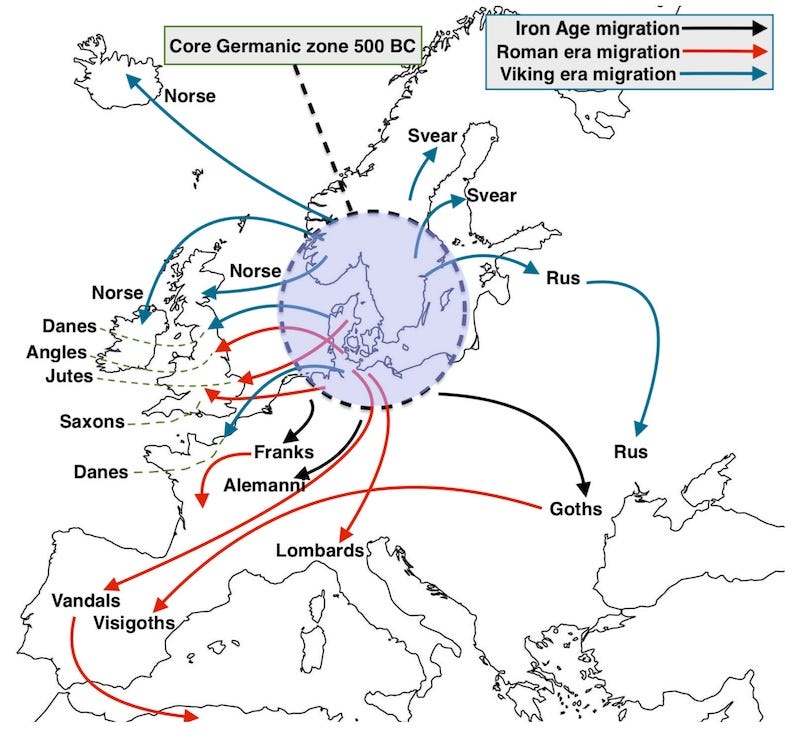

To hear most English sources tell it, the Viking Age suddenly began in 793 AD when Scandinavian raiders wantonly slaughtered defenseless monks at Lindisfarne on Britain’s northeastern coast. But this was really just the moment Latin Christendom was finally forced to acknowledge the ferocity of Scandinavia’s heathen marauders. Groups of young Viking men had been pulling off less decisive, small-scale raids across northern Britain over much of the 8th century, but these flew beneath the notice of English chroniclers. Lindisfarne’s other name was Holy Island; it was a major node within early Anglo-Saxon Christianity that served as the burial ground of saints. What happened at Lindisfarne was the first detonation of an explosive phenomenon that had been building pressure for generations across Western Europe. After 793, Vikings would challenge the princes of Ireland in their hillside forts, Charlemagne’s heirs at the walls of Paris, and rulers of the English kingdoms from Hadrian’s Wall to the gates of London. But before 793, the evidence for Scandinavian raiding is much more striking and unequivocal in Eastern Europe, along the frigid shores of the Baltic, from the lands of the Finns in the north to the Slavs’ forests in the south. Once you get beyond the limitations of text and call in the tools of archaeology, the evidence for significantly earlier Viking incursions in the east, long before massed Viking attacks in the West, is undeniable.

A century before the sack of Lindisfarne, around 700 AD, more than 40 men were buried with two ships on the island of Saaremaa, just off the coast of Estonia. Isotope analysis of the bones tells us that these men grew up in the Mälaren Valley of Sweden, more than 200 miles to the west. Discovered in 2008, this site is evidence of a massive raid probably emblematic of a whole era of intense activity that our reliance on textual sources left hidden from our view. The buried men ranged in age from their teens to their 40’s, and were inhumed along with dogs and hawks killed to accompany them into the afterlife. Many were tall, suggesting good nutrition. The extensive weaponry befitting elite Viking warriors indicates that they had been killed in battle. In pagan Scandinavia, high-status dead were buried with rich grave goods, but those intentionally inhumed on a ship, which was then bizarrely, and obviously at great inconvenience to the survivors, buried on land, were particularly elite. Their possession of forty-odd expensive, finely crafted swords is further evidence that theirs was not an ad hoc voyage. Four of the individuals were brothers, and also buried with them was an apparent uncle. The presence of multiple near-relatives argues this sortie was pre-planned and undertaken by groups of men known to each other rather than assorted adventurers thrown together by need and opportunity.

Clearly, these Scandinavian warriors had planned to conquer and plunder lands across the Baltic Sea decades before the Vikings would make their presence known to Western European chroniclers. But Scandinavia and the East Baltic, as well as what would become Russia further inland, were pagan and illiterate in the 7th century. These were the stomping grounds of unlettered warriors who left future generations no written memorials to their victories and defeats. The rich burial of numerous well-armed men so far from their birthplace points to a substantial expedition gone wrong. If more than 40 men died and two ships were dragged ashore and buried, likely many hundreds more lived to be able to honor their dead comrades before departing Estonia for their homeland in their remaining ships, presumably to fight another day. The surfeit of expensive weaponry also marks all these men as members of Scandinavia’s ruling warrior caste. Later chroniclers’ descriptions of these sorts of expeditions led by northern elites gives us a good idea of the massive scale of this lost eastern army becoming known to us only through their material remains.

For all practical purposes, traditional Western sources are blind to this vast world that centuries later gave rise to Kievan Rus. But by 700 AD this region was already deeply integrated with Scandinavia through both trade and war. A default tendency to apportion the east of the Viking Age to Sweden and the west to Norway and Denmark has tended to elide the important reality that the Scandinavian world was a smooth continuum, from Iceland to Greenland, all the way east to Rus settlements along the Volga. These were all people who spoke the same language, worshiped the same gods, and practiced the same rites. This border-free reality is illustrated in the life of Geirmund the Hel-skinned, born in western Norway at the end of the 9th century. Fathered by a petty sea-king, Geirmund’s mother was a Samoyed from north-central Siberia whom his father presumably encountered on his travels east. Geirmund’s nickname came from his dark skin inherited from her. He migrated westward, initially to Ireland, but his ultimate fate was to become one of Iceland’s early settlers, on the far western edge of the Viking world. Which is how the first Icelandic noble came to have a Siberian mother.

The literary chronicles we have always relied upon illuminated only a small fraction of the journeys that must have occurred out of Scandinavia during this period of dynamism. Even then, the written record and oral sagas still testify to the audacity of Vikings across much of Western Eurasia in the two centuries before 1000 AD. An army of Scandinavians laid siege to Paris in 845 AD, and within a few decades, the Dane Rollo and his followers had taken the northern coast of France, what became Normandy. But France was only to be a launching pad for forays further south. In the middle of the 800’s, Vikings began regular raids on Muslim Spain, and in 860, a group led by Björn Ironside sailed into the Mediterranean and after raiding North Africa, attacked Liguria in northwest Italy. Though the explicit written record fades out after the Italian raids, there are allusions to a voyage by Ironside’s ships to Constantinople that would have enabled these Vikings to return to their homeland via the waterways controlled by their Rus cousins.

It was at this time that the Rus, led by a chieftain named Rurik, took command of the northern Russian city of Novgorod, and immediately moved south to lay siege to Constantinople. Rurik’s sons eventually relocated their capital to Kiev in 880, and so laid the foundations of the later Russian state. Offshoots of the Rus became corsairs of the Caspian Sea, with some taking cities in what is today Azerbaijan. By the early 12th century, rulers of Scandinavian origin held parts of France (Normans), all of England (Normans), southern Italy (Normans) and Russia (Rurikids). Finally, not all the adventures of the Scandinavians involved conquest. Scandinavians from Norway arrived in Iceland in 870, then pushed on to Greenland and North America in the 980s, becoming the first Europeans to reach the New World.

The Vikings retain a legendary status today, and were objects of fear more than 1,000 years ago, because they were the last of the pagans of a northern world that had repeatedly terrorized Rome and given birth to the barbarian kingdoms of antiquity. By 800 AD Scandinavia was an anachronism, a throwback to the ominous murky forests beyond the frontiers of Roman civilization, the abode of tattooed tribes practicing blood sacrifice under the gaze of wooden idols of Odin. The Vikings were aliens in the new Europe, obstinate holdouts in an age now dominated by fealty to a God who promised the meek salvation and peace, rather than a raucous mead hall to warriors felled in glory. The flip side of Viking brutality and audacity was their aversion to hierarchy and their full-throated embrace of their freedoms. They rejected Christianity’s rarefied themes that had been refining European society to their south.

The northern pagans’ campaigns were the last eruptions of old Europe’s ancient instincts, brutal relics of a prehistoric world out of step with the societies that would go on to birth our contemporary age. Viking isolation from civilized currents after Rome extended beyond their cultural difference; Scandinavian genetics shows evidence of biological isolation in the Viking Age, and subsequent integration into the European world. Twelve hundred years ago, after a somnolence of several centuries, the north kindled back to life. The last pagans swarmed forth a final time, fearsome agents of Europe’s deep Bronze-Age past running roughshod over Christian neighbors poised on the threshold of building a modern Europe.