France: Europe’s crème de la crème

Why the French always seem to regain the upper hand, a geographic and genetic exploration, part 1 of 2

Note: Part 1 of 2

Hugh Capet was crowned King of the Franks in 987 AD, the first in an uninterrupted 861-year string of French rulers to reign over Western Europe’s most populous state right through to the beginning of the Victorian age. Bounded by water on its west, north and southeast, and fringed by mountains to the southwest and east, France's only significant open border is in its northeast, abutting the lower reaches of the Rhine River valley. Even before it existed as a nation-state, these natural constraints circumscribed a coherent social, cultural and political unity; a 2000-year-old map of Roman Gaul remains roughly a map of France today.

On a continent where Northern is routinely juxtaposed to Southern, Eastern to Western, France, above all others, remains the very embodiment of the West, one half facing north and another the gateway to the south. From the beginning, it was the heart of what became the civilization of Latin Christendom. Obviously, Ireland and Iberia lie further west, but concrete as those details of geography are; both domains are only liminal to Western identity. To the south, Petrarch and Michelangelo’s Italy powered the cultural resurrection of a fallen world post-Rome, but the specter of an imperial greatness never remotely regained would always haunt Italians. Britain and Germany have allegiances beyond the Western Atlantic world: Britain, with its medieval Nordic entanglements and Germany, freighted with the baggage of its Baltic Prussian origins. France alone, “eldest daughter of the church,” could furnish Western Europe a fulcrum around which to rebuild its civilization in the wake of Rome’s collapse. Both home to the first medieval cathedral in Sens and the world’s early modern tastemaker in high culture, France’s identity was coterminous with that of the West.

France, despite its position on Europe's furthest Atlantic edge, serves as a cultural and historical bridge between the southern Latin Mediterranean and northern Germanic domains. Although the French speak a daughter tongue of the Romans and take their name from their later German Frankish conquerors, early 20th-century French children’s textbooks began declaring the people to be descended from prehistory’s Gauls, claiming ties of blood and descent that genetics would later confirm. The fixed realities of location mean that France would always be the north’s gateway to southern civilization and the south’s throughline to northern vigor; from Rollo’s Danes in Normandy to Greeks in Marseille and Britons in Brittany, Eurasia’s most climatically fortunate promontory, with well-watered plains and mild temperatures, absorbed all comers, transformed them and was in turn transformed by them.

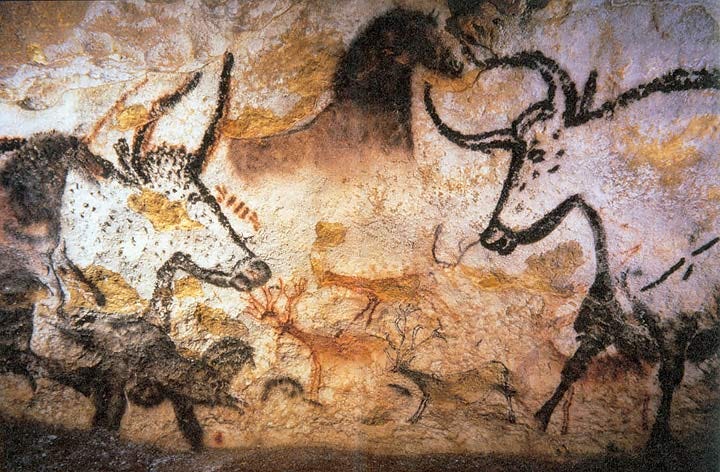

This central role predates history. When modern humans streamed out of Africa into West Asia, and then pushed westward out of Eurasia’s heart, Iberia was the terminus of their journey and where the last bands would finally gaze back from Eurasia’s furthest edge across to a fresh shore of the mother continent. But before Iberia, they reached the Atlantic and the end of the North European plain between the Pyrenees and the North Sea, a land at equipoise between the south’s aridity and blasting heat and the north’s forbidding frigidity, a realm that is today Europe’s agricultural superpower, and during the Ice Age hosted vast numbers of prehistoric humans under conditions that inspired them to populate the walls of their cave complexes with some of the world’s first attested representational art.

France’s centrality to European history is an accident of its location, facing the Atlantic and blessed with good fortune denominated in the abundance of its harvests. The land’s plentitude has made it a perennial human-population magnet, from the first modern bands who arrived more than 50,000 years ago fleeing the Eurasian heartland’s ice and chill, through the Romans, Visigoths and Franks, right down to today’s migrant groups from Francophone Africa. The France that Hugh Capet inherited, a nation that received the mantle of Imperial Rome in Charlemagne’s age, had an ambition and arrogance that would not be curbed until Napoleon’s time. It was just the last iteration of a nation whose peoples have waxed in power, prodigy and audacity: the Gauls of Vercingetorix, whose wealth drew Roman greed and challenged Roman might, the nameless Neolithic megalith builders whose mighty works still stud the Breton headlands and spangle shores all the way north to Scandinavia and south to Malta, and even earlier, during the long Ice-Age epoch when an explosion of Paleolithic creativity bore witness to the rise of the modern mind in addition to modern human lineaments.

The Pleistocene painters

In 1940, Frenchman Marcel Ravidat, an 18-year-old apprentice mechanic out hiking with his friends, happened upon a cave in southwest France whose interior seemed to house an enormous cache of prehistoric art. He and his friends guarded the cave’s entrance throughout World War II, anxious to protect it from vandals, and in 1948 Ravidat’s lifelong association with the cave was sealed when he began guiding visitors on tours. Inside they could behold 6,000 figures depicted on the walls, ranging from extinct animals, like the Irish elk, woolly rhinoceros and cave lion to humans, plus more abstract and inscrutable motifs whose meanings we can only guess at. Mineral pigments granted the artists a palette of various shades, lending their tableaus an even more lifelike profile, with red, yellow and black still clearly visible to us these many millennia later.

Over half the figures on the cave walls are horses. This suggests the artists’ activity was ritualistic rather than a cold accounting of daily lives, because the Magdalenians were famously reindeer hunters. Reindeer bones litter their sites, indicating these were their primary food source. The absence also of mammoths, whio disappeared from Europe 20,000 years ago, allowed for rough dating to the latter part of the Ice Age, well after the Neanderthals had also disappeared. Indeed modern methods confirm that the paintings were created some 17,000 years ago, over five millennia before the dawn of our Holocene age 11,700 years ago. Europe at the end of the Pleistocene was cold and dry, with steppe-tundra dominating much of the northern plains. But conditions had become considerably milder since the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) 20,000 years ago, easing our species’ reoccupation of regions long sealed beneath glaciers. More generally, a human population boom hit across Northern Europe because of the proliferating megafauna herds, as cultures that had retreated to southern refugia in Iberia, Italy and the southern Balkans reclaimed newly abundant points north.

Ravidat’s cave is called Lascaux, and it is one of the major early sites for a prehistoric culture known to archaeologists as the Magdelanian. Associated with a particular toolkit and artistic traditions, the culture draws its name from the society’s first site discovered in 1863 at southwestern France’s Magdalene Shelter. The Magdalenians flourished for about 5,000 years, beginning 17,000 years ago, just as they were first ornamenting the walls of Lascaux. They disappeared only a few centuries before the end of the last Ice Age, recording an uninterrupted duration for their society that knows no analog in our time, the equivalent of a single people enduring from the rise of ancient Egypt all the way to today. Aside from their artistic productivity, the Magdalenians are notable as the last of Europe’s great Ice Age societies, the climax of an arc of cultural evolution dating back to the extinction and replacement of Neanderthals 40,000 years ago. The precedent for the Magdalenian tradition of cave painting goes back to the far earlier Aurignacian culture; these early Europeans began creating art that reflected their life and their legends in caves as early as 35,000 years ago at sites like Chauvet. This means that the artistic tradition the Magdelanians inherited was 18,000 years old by the time they began painting at Lascaux, a longer span than has yet elapsed from the Magdelanians to us today.

Though Magdalenians ranged as far east as Poland, and to Spain’s far south in Gibraltar, the bulk of their sites cluster in France and along Spain’s northern fringe, up against the Pyrenees. Ice-Age Western Europe’s tundra was rich in herbs, grasses and shrubs, a bounty that could sustain herds of mammoth, giant deer and steppe bison. Our modern associations with “tundra” do not apply; the ecological richness more resembled the African savannah than frozen and wind-blasted Siberia or Alaska. A relatively mild Atlantic climate and a flat topography blessed France’s northern and western plains, then as now. Endless grasslands in their turn supported vast herds of megafauna, the economic base for rich forager societies. Today the planet’s rare hunter-gatherers are cultural fossils, surviving only on the marginal lands farmers and pastoralists begrudge them, but during the Pleistocene they occupied choice territories. The vast herds wandering open grasslands across northwestern Europe’s coastal plains, which are today France, explain the density of Paleolithic European sites from the mouth of the Rhine in the northeast, to the Pyrenees in the south.

Our modern lineage: gracile, with high foreheads and prominent chins, evolved first in Africa over 200,000 years ago. But those anatomically modern societies remained changeless culturally, their turnover of artistic traditions proceeding at a snail’s pace compared to that we have seen over the last 40,000 years. It is in late-Pleistocene Western Europe that modern humans finally flexed their cognitive muscles in massive bursts of cultural creativity, a fact clearly reflected in the archaeological record via humanity’s first realistic artistic representation, likely unleashed by the complexity and scale of their societies first generating enough economic surplus to allow for either leisure or the emergence of vocational specialization. What Jared Diamond has termed our species’ cognitive “great leap forward” was likely underwritten by the clement economic conditions of Pleistocene Western Europe.

Until recently, our understanding of these Ice-Age societies tended to unfurl solely through interpretation of their artifacts and analysis of their fossil remains. But over the last twenty years, ancient DNA has brought to life genetic relationships between individuals and peoples at a granularity that was even recently entirely unimaginable. DNA from Magdalenian sites has clarified their relationships to their Pleistocene predecessors and to the modern European inheritors of their ancient territories. Paleogenetics tells us that the artists of Lascaux were not just cultural heirs of earlier Ice-Age Europeans, they were the genetic descendants of the first Aurignacian cave painters.

The earliest anatomically modern human site in France is in the Rhône valley and dates to ~55,000 years ago. But Neanderthals eventually reoccupied the site, and they do not disappear from the European fossil record until about 40,000 years ago, so we now know the handoff between the two lineages of humans was more halting and complex than previously described. But by 40,000 years ago, modern humans were in Western Europe to stay, an age of abortive colonization attempts now behind them, as their Neanderthal competitors disappeared from the fossil record. This period saw the emergence of what became the proto-Aurignacian cultural toolkit: long blades, bone points and antler tools. These were far different from the more traditional flake-based blades and scrapers that the Neanderthals had used for hundreds of thousands of years. The Aurignacians’ ancestors had recent roots in Africa, 60,000 years ago, at the latest, part of the most recent migration out of the mother continent. But they themselves had migrated out of the Near East, and pushed into Eastern Europe along its southeastern Balkan fringe, as early as 45,000 years ago.