Everywhere you want to be: Indian immigrants in America (part 2 of 2)

A new America living up to its creed

Note: part 2 of 2 (read part 1)

Anyone who has given statistics on Indian Americans so much as a cursory glance will note immediately that this is a band of outliers. Nearly 80% of Indian immigrants in America over the age of 25 have a bachelor’s degree. This compares to 33% in the general American population. They contribute higher labor force participation than the overall population, 72% vs. 67%. More than 75% of Indian immigrants work in management, business and science (as opposed to 41% of the general population). No surprise either then, that Indian-immigrant median household income is considerably higher than that of Americans overall, ($132,000 vs. $66,000 in 2019). And this has been true for decades. In the year 2000, Indian-American household income was $71,000, vs. $42,000 for the general population.

Indian Americans’ unique socioeconomic profile is a straightforward function of how they arrived in the US. In 2021, 81% of Indians who received immigrant status in the US attained it via employment-based preferences, with only 18% immigrating because they were immediate relatives of US citizens or eligible for family-based sponsorship (in contrast, 61% of all legal immigrants to the US arrived via connections with US citizens or through family-based sponsorship). Extremely highly skilled Indians often aspire to migrate to America; 35% of graduates of the elite Indian Institute of Technology go abroad after graduating, most of them to the US. India’s extensive system of affirmative action also has driven certain professionals like physicians from castes disadvantaged by quotas to emigrate in search of less constrained opportunities. Depending on the statistic you accept, people of Indian origin are 5-9% of the medical doctors in the US, while representing only 1.35% of the population.

Obviously, overall India is a large poor country, with vast swaths of the interior north posting incomes and quality of life indexes similar to Sub-Saharan Africa. But unlike other postcolonial states, India always had an indigenous elite ruling class. Or, more precisely, numerous distinct indigenous ruling classes. Whether the rulers were native princes, Muslim potentates or British viceroys, literate communities across the subcontinent were available to staff the bureaucracies, while the mercantile communities played out their traditional intermediation and arbitrage roles irrespective of religion or origin. It is unsurprising that the first Indian-origin Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Rishi Sunak, is a product of the East African Indian diaspora, which still controls substantial proportions of the economy in Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania. East African Indians in the United Kingdom are the wealthiest and most educated subset of the UK’s nearly two million Indians, hailing disproportionately from various communities in the western coastal state of Gujarat.

Economic historian Gregory Clark finds that the Indian subcontinent exhibits the highest level of intergenerational social status transfer of all societies he surveyed; class is 90% heritable for Indians. The cultural and genetic data hint at many thousands of years of social status stability in India; though Clark’s work shows that this holds true across many societies, it reaches its peak value in India. All signs point to this comparatively high social status still translating faithfully in the US.

Because the US was never a colonial power in Asia (save for the partial exception of the Philippines), Indian Americans arrived after 1965 seeking educational and professional opportunities in a country where they had neither pre-existing personal nor historical connections. In the second half of the 20th century, the US was an industrialized economy with little need for agricultural labor, so the peasant majority of India were never lured to American shores. Their skills were not needed. Instead, America skimmed off a layer of India’s professional elites.

This is clear in the caste-origin representation of Indian Americans. In India itself, 28% of Hindus are “General Category," meaning they do not qualify for any affirmative action, unlike Dalits (“untouchables”), indigenous tribes or adivasis and “Other Backward Classes” (OBCs). A survey of Indian-American Hindus reports that here they are instead 83% General Category, 16% OBCs (vs. 35% of Indian Hindus) and 1% Dalits or of adivasi origin (vs. 35% of Indian Hindus). Private surveys have shown that 25% of Indian Americans are Brahmin, in contrast to 5%, at most, of Indians.

Emma Lazarus’ The New Colossus famously begs, “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…” But that seldom describes Indian immigrants to America. This is not to suggest that they were wealthy or even middle class in the subcontinent, especially on an American scale of material well-being. Simply that compared to the broader Indian public, they were disproportionately near the pinnacle of the socioeconomic distribution, and even if they were not materially well-off, they likely enjoyed at a minimum the human capital of being highly literate. They served the elites. Or they were the elites.

But the magnitude of Indian Americans’ success in the US could almost be explained away as America’s own special sauce. This nation has a proven track record of leveraging underutilized human capital, and transforming people into engines of dynamism and creativity. More than a century ago European Jews fled a continent that was turning against them, correctly judging that it was on a nosedive into authoritarianism and self-destructive nationalism. In the US, they found a country that needed them, where they could make outsized contributions to science and the arts, and dominate large swaths of popular and elite culture for the better part of half a century. Depending on your vantage, the expectation, hope, or perhaps fear, is that Indian Americans may play the same role. But is the analogy of Indian Americans to Ashkenazi Jews actually so apt, as the American century approaches its golden years?

Rise and fall

In the wake of World War II, Jews totalled more than 3% of the American population. Today they are 2% or less (depending on how you count). American Jews are far older than the average citizen, and they have lower fertility rates. The visible decline of Jewish American prominence today is not the outcome of a conspiracy, but the inevitable result of simple demographic decline. They have high rates of outmarriage, low fertility, and can no longer rely on diaspora communities to replenish them demographically, like Russian Jews did in the 1980’s and 1990’s. Perhaps the starkest evidence of Jewish influence’s high tide in elite circles being far behind us is the decreasing proportion of Jews among Ivy League student bodies.

If this is true, is it Indian Americans who will in turn next assume the role that Jews accepted from New England WASPs before them? Many seem to think so; in 2008 at the height of the financial crisis, Jewish-American pundit Matthew Yglesias opined that the appointment of Neel Kashkari to oversee the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) rather than a Jewish American signaled a passing of the guard. But I see reasons for skepticism that Indian Americans will prove the kind of force in American culture that Jews were in the 20th century.

Though American Jewish identity evolved into its own distinctive form, it did not originate de novo in the US. For centuries, European Jewry itself shared a cohesive internal identity with multiple disparate points of contact with gentile culture. Whether from Germany, Lithuania, Poland or Hungary, Ashkenazi Jews shared a common ethnolinguistic and folk culture continent-wide. Lightly worn European national identities quickly melted away in the US as a common Jewish culture instead bound them together, no matter if they were nominally German, Polish, Hungarian or Russian. Yiddish theater flourished in the first half of the 20th century in the US because of this vast concentrated urban and culturally monolithic clientele transplanted to the New World. Genetically and historically, the Ashkenazim descended from a population that arose in Germany less than 1,000 years ago and underwent massive expansion after 1500.

Indian Americans, by contrast, are many distinct peoples with radically different histories, now experimentally coalescing together as one in America. But this does nothing to erase their diversity of language, unique communal religious traditions and regionally specific folkways. The common culture of a Punjabi American and Tamil American is partly pan-Indian traditions and forms, but it is also partly (perhaps mostly) American culture. Additionally, there is the matter of numbers. Today Indian Americans are 1.35% of the population. Like many Asian American groups, their fertility is below replacement, so the community grows through immigration. But at least in the short-term, the number of Indians in America will be capped because of the nature of our immigration system with its quotas for each nation, limiting the inflow from very populous nations (the current backlog of pending applications eligible for immigration from nationals of India is one million).

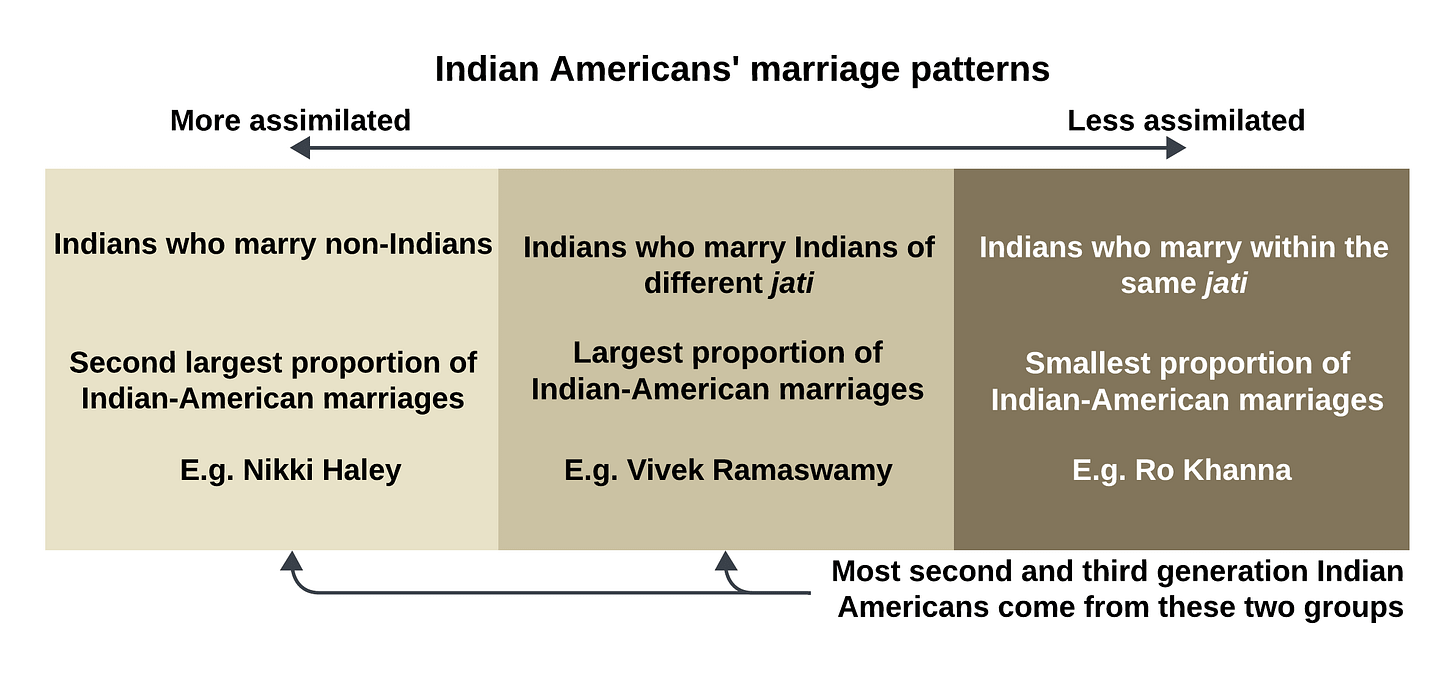

Finally, there is the matter of intermarriage. Though the US was very accepting of Jews compared to the Europe they fled, early 20th-century American attitudes to mixing were starkly different from America today. Jewish intermarriage with non-Jews was 3% after World War II, rising to 7% in the 1960’s, and plateauing at 50% in this century. Jews in America had two to three generations of existence as a vibrant endogamous subculture in a relatively open society. White gentile America viewed intermarriage with Jews as they viewed interracial marriages; this is clear in 1939’s piece in The Atlantic, “I married a Jew,” which serves as a sort of exposé. The late 20th century was very different. The children of Indian Americans already out-marry at rates of 30% (and have been doing so for a generation), a point American Jews only reached by the 1980’s, nearly a century after the beginning of mass Jewish emigration. The America that incubated Jewish prominence in the 20th century imposed a timeless tug-of-war between acceptance and alienation which had the side effect of nourishing a Jewish-American world unto itself centered on major East Coast cities. A much more permissive 21st-century America arguably has a stronger absorptive capacity (or corrosive power vis-a-vis distinct microcultures) that probably spares Indians anything analogous to the kind of conditions under which Jewish culture flourished as an enclosed world. More likely, by the middle decades of this century we will see a mixed Jewish, WASP, Indian and East Asian elite, studded with random overachievers from all ethnicities.

Indeed, looking particularly at the earliest generation of Indian-Americans who grew up in the US and are so prominent in American political life today, my own generation, I will say anecdotally that my experience of usually being the lone Indian-origin kid in my entire school throughout my childhood seems tremendously common. That full cultural immersion in random outposts of American society stands in sharp contrast to the massive cohort of young Jewish Americans who came of age in dense east coast enclaves run by other people like their European immigrant parents.