Dark Horse out of the Steppe

Fishing the Sintashta, Scythians and Sarmatians out of obscurity

Lift up a battle standard in the land. Blow a trumpet among the nations. Consecrate the nations against her. Summon the kingdoms of Ararat, Minni, and Ashkenaz against her. Appoint a commander against her, bring up horses like bristling locusts.

Jeremiah 51:27

Do you find it odd if I tell you a 2020 Tesla Model 3 was measured registering a horsepower of 523? An electric vehicle’s... horsepower? Like the “folders” on the “desktop” of a computer, “horsepower” is an anachronism, jargon we use unquestioningly, but which joined our language when the horse was still a universally grasped measure of work (as in basic physics, where work, W, is force, F, multiplied by distance, s, so that W = Fs). But whereas physical folders had one century of ubiquity, the age of the horse spanned millennia. The relationship between humans and our primary beast of burden probably began more than 5,000 years ago, when the earliest Indo-Europeans and their neighbors on the Eurasian steppe mounted animals they had long hunted for meat, choosing instead to co-opt their speed and endurance. But perfecting the horse as a work and war instrument as well, seems to have occurred more recently, only with the development of associated technologies like the light chariot and the saddle. These made full use of equine muscle-power, turning what had been merely been a tamed beast whose fleetness we harnessed, into a technology whose influence came to pervade all aspects of human society.

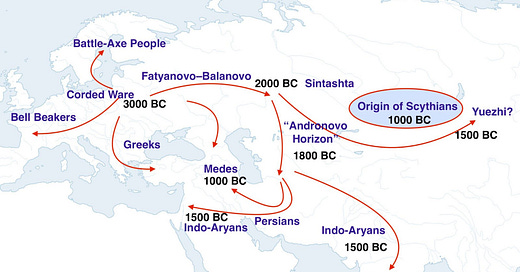

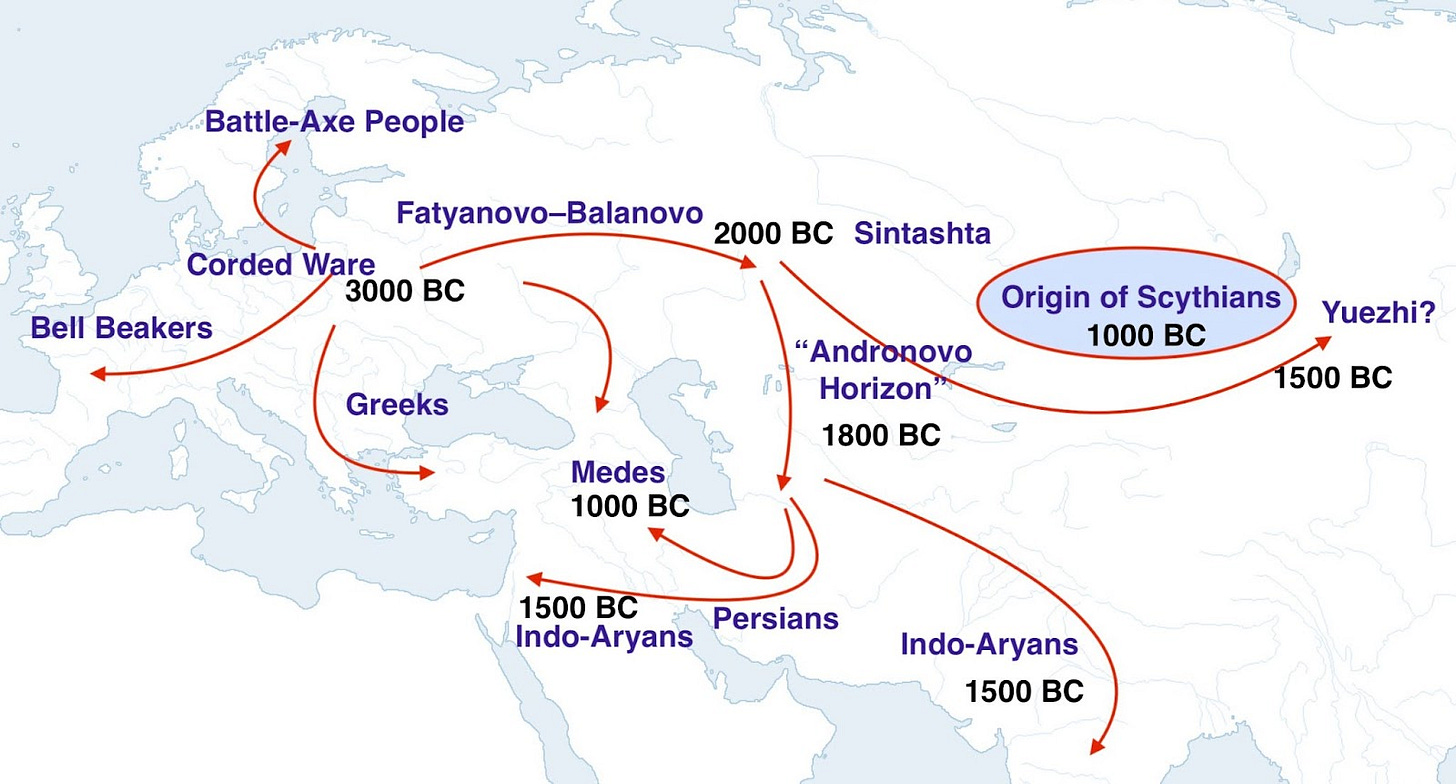

This final taming of the horse began 4,000 years ago on the steppes north of the Caspian Sea, among the Indo-Iranian pastoralists. The ancient Assyrians came face to muzzle with the fearsome descendants of these steeds 1,000 years later. They called the mounted riders that destroyed their world the Aškūza, or Ashkenaz in Hebrew (a term coincidentally later recycled for those Jews who settled in Europe north of the Mediterranean). These were nomads who had migrated from north of the Caucasus down into the uplands of eastern Anatolia, plundering and pillaging as they went, finally tearing apart the Assyrian Empire in the seventh century BC. Their name for themselves was Skuδa, “archer” in their language, from the Indo-European root “shoot.” The Persians would know them centuries later as the Saka, while far to the east, the Chinese called them the Yuezhi, or “meat-eaters”. In the West, they became Scythians.