Chariots of Ice, Coursers of the Sun

Scandinavia’s Golden (Bronze) Age at globalization's first light

Related: After the Ice: how foragers and farmers conquered Scandinavia, The 100-year-winter and the coming of Ragnarök and Fury out of the North: from pagan slavers to Christian kings.

In 793 AD the “Viking Age” began with the sacking of Lindisfarne monastery on the northeast coast of England, then the kingdom of Northumbria. Scandinavian raiders had been probing northern Britain for decades. But their ferocity at Lindisfarne was culturally decisive because it was the seat of Northumbrian Christianity. On the monastery's grounds, two saints of great renown were buried: St.Cuthbert and St. Aidan. Alcuin, an eminent Northumbrian scholar at the court of Charlemagne, wrote that “heathens poured out the blood of saints around the altar, and trampled on the bodies of saints in the temple of God, like dung in the streets.” The early medieval world was brutal, but the pagan Scandinavians announced their arrival with an unprecedented level of blasphemy, wildly transgressing even the norms of an already violent Christian Europe. Over a millennium later, the absolute horror of the clerics standing witness to the destruction and barbarity comes through palpably in their accounts.

Contemporary European chroniclers called these northern attackers heathens, from “heath dwellers,” because of paganism’s backward connotations. But the northerners saw themselves as a collection of tribes with individual identities, the Rygir, Svear, Geats, Danes and Ruges. These Vikings, a neologism from the Old Norse vikingr that referred to a class of young men engaged in raiding, did not just leave an ephemeral stamp on the imaginations of late 8th-century Christian observers. Their aura of menace and threat held the attention of Western Europeans for two more centuries, and today their deeds still inspire a notable tranche of popular culture, from television series like Vikings to films like The Northman, in addition to providing essential framing elements for the character of Thor and his homeworld Asgard in the Marvel Universe. The memory of the Vikings persists over a millennium after their heyday because of both the nature and magnitude of their exploits.

The enduring fascination with the Vikings owes a debt to medieval Icelandic noble Snorri Sturluson, who single-handedly preserved a substantial corpus of his pagan ancestors’ mythos. Sturluson’s effort is responsible for the gulf between our knowledge of Scandinavian mythology and that of either the Germans or Anglo-Saxons, whose pagan myths and legends have persisted only in fragmentary folk culture. J. R. R. Tolkien created Middle Earth and its associated myths in an attempt to offer the English a synthetic mythology on par with the Scandinavians. So few native sources captured these traditions that the ancient Roman historian Tacitus actually provides one of the best ethnographic surveys of pagan German religious practices, even if it is entirely hearsay.

There is another deeper, historical reason for this difference. German and Anglo-Saxon pagans were Christianized soon after the fall of the Roman Empire, barbarians just outside the frontiers of civilization, beyond whom lay vast realms of always threatening pagan tribes. Their indigenous beliefs were deemed part of their alien and demonic past, to be abolished and forgotten, and akin to the frightening living tradition still vigorous across Europe’s north and east. The Viking-Age Scandinavians, in contrast, had a deep, centuries-long engagement with Europe and only a comparatively belated conversion to Christianity. These were pagan people who remain real to us through the recollection of vivid and bloody rites, and through fully fleshed-out tales of heathen kings and warlords like the first Norwegian high king Harald Fairhair or the pagan traditionalist Haakon Sigurdsson.

Sturluson’s proximate intent in assembling and writing the Prose Edda, his mythic history of the Norse gods, and collecting the Heimskringla, a compilation of sagas, was probably to burnish the reputation of the Scandinavian Christian monarchs then attempting to consolidate their domains. A heroic pre-Christian past provided Scandinavian kings with prestigious and unique cultural roots to legitimize their rule and a corpus of high-toned narratives that celebrated the glory of conquest and valorized the domination by the great over the humble. Though the last pagan Scandinavians do not speak to us with the enduring power of the pagan Greeks, whose philosophical reflections and artistic works provide the foundation for Western civilization, their world-view exists for us with a specificity far beyond just faintly recalled memories and the hollow echo of time-attenuated folk practices.

And yet to a great extent, we know the Vikings through the eyes of their enemies. The Christian priests of 900 AD explicitly described the beliefs and practices of the heathen corsairs to generate propaganda in their centuries-long fight back against their attackers. In contrast, modern Western audiences thrill to popular culture depictions of the Vikings as swashbuckling heroes, exempt from the suffocating restraints of Christian morality and breathing the free air of the noble savage. But the villains and heroes both fans and detractors like to imagine did not stride into the Viking Age fully formed. The Viking Age’s history, its origins, and prehistoric roots go back thousands of years to an age when far to the south, warlords in Bronze-Age Mycenaean Greece sent missions northward to exchange gold for amber, knitting the far-flung corners of a barbaric Europe together through force of will and at the point of the spear.

Archaeologists have historically divided Scandinavian prehistory into sequential periods, beginning with the Mesolithic, followed by the Neolithic, and then the Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages (these last three ending in 1750 BC, 500 BC and 800 AD, respectively). Before the 1st-century AD development of runic alphabets among the Germanic people, we know the region's prehistory through material artifacts and glancing mentions in Roman and Greek sources. However, scholars had little choice but to speculate on the origins and relationships of archaeological cultures across the region. Today at least on this count, genetics contributes a precise accounting of the demographic context with a degree of finality once unfathomable.

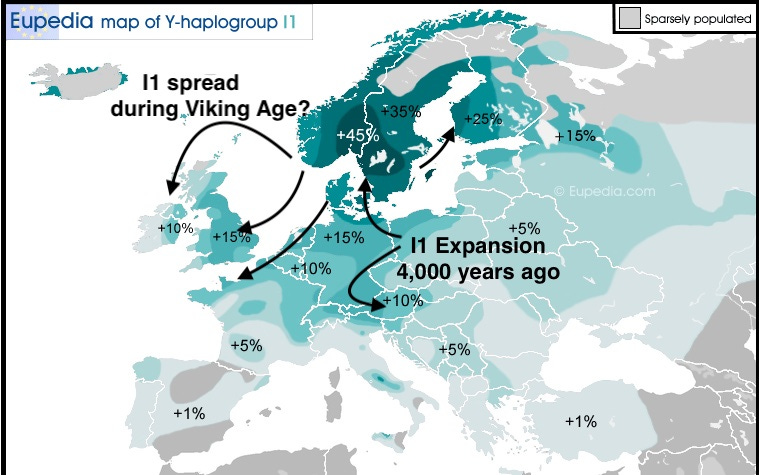

It is clear that genetically, Viking-era Scandinavians were not descended from indigenous Mesolithic foragers or Neolithic farmers. Instead, the biological character of the region’s population only begins to resemble modern Scandinavians with the arrival of the Battle Axe Culture 4,800 years ago. But this is not the last chapter in modern Scandinavians’ origin story either, because significant genetic and cultural changes hit around 2300 BC, and then again around 1750 BC, at the beginning of the Nordic Bronze Age. At this point, a people entirely ancestral to Vikings, genetically and culturally, coalesce. And so, to understand the Vikings’ roots, and those of their modern-day descendants, we need to go back to the Nordic Bronze Age, some 3,750 years ago.