Bantu über alles: three millennia of unstoppable African farmers repeopling the vast continent

Humanity’s last great agricultural revolution

Related: Shaka Zulu: The Last of the God-Kings.

In the late 1700’s, after more than a century colonizing the Cape of Good Hope’s hinterlands, Dutch settlers finally clashed with clans of Xhosa herders east of the Great Fish River. Along the farthest southern coast of Africa, the Great Fish looms large, marking the disjunction between the Cape’s dry Mediterranean climate and the moist, subtropical zone that eventually bleeds seamlessly into the tropical regime regnant across so much of the rest of Sub-Saharan Africa. Here, the European colonists first encountered Bantu-speaking Africans, the Xhosa tribe whose most famous son was the late Nelson Mandela. Thus began a series of drawn-out wars that continued to flare up periodically into the 1800’s and eventually saw all of modern South Africa brought under European rule.

In making this push east, the Dutch-speaking ancestors of the Boers, the migratory component of the Afrikaner population who were expanding outward from Cape Town into the bush, finally forded the chasm between two radically different ecologies. Their campaigns took them from Africa’s southwestern tip, with its sun-soaked vineyards to the lush pasturelands that gently give way to savanna further north and east. The Boers' journey eastward exposed them to a Bantu culture as alien to the Cape’s native Khoekhoe as that of the Europeans. The difference between the Xhosa and Khoekhoe was stark even physically; where the former resembled the dark-skinned population of most of Sub-Saharan Africa, the latter were of a light-brown complexion, with high cheekbones, delicate features and narrow eyes more reminiscent of East Asians than Africans. The Xhosa were the southernmost of the Bantu-speaking peoples, a language family that today covers over 30% of Africa’s vast landmass (and some 40% of its arable reaches) and accounts for the same proportion of the continent’s population. If the Khoekhoe were the echoes of the South African Neolithic, with roots back to the Ice Age and prior, the Xhosa were firmly of South-Africa’s Iron Age, arrivistes who brought new technologies and lifestyles to the region around 300 AD.

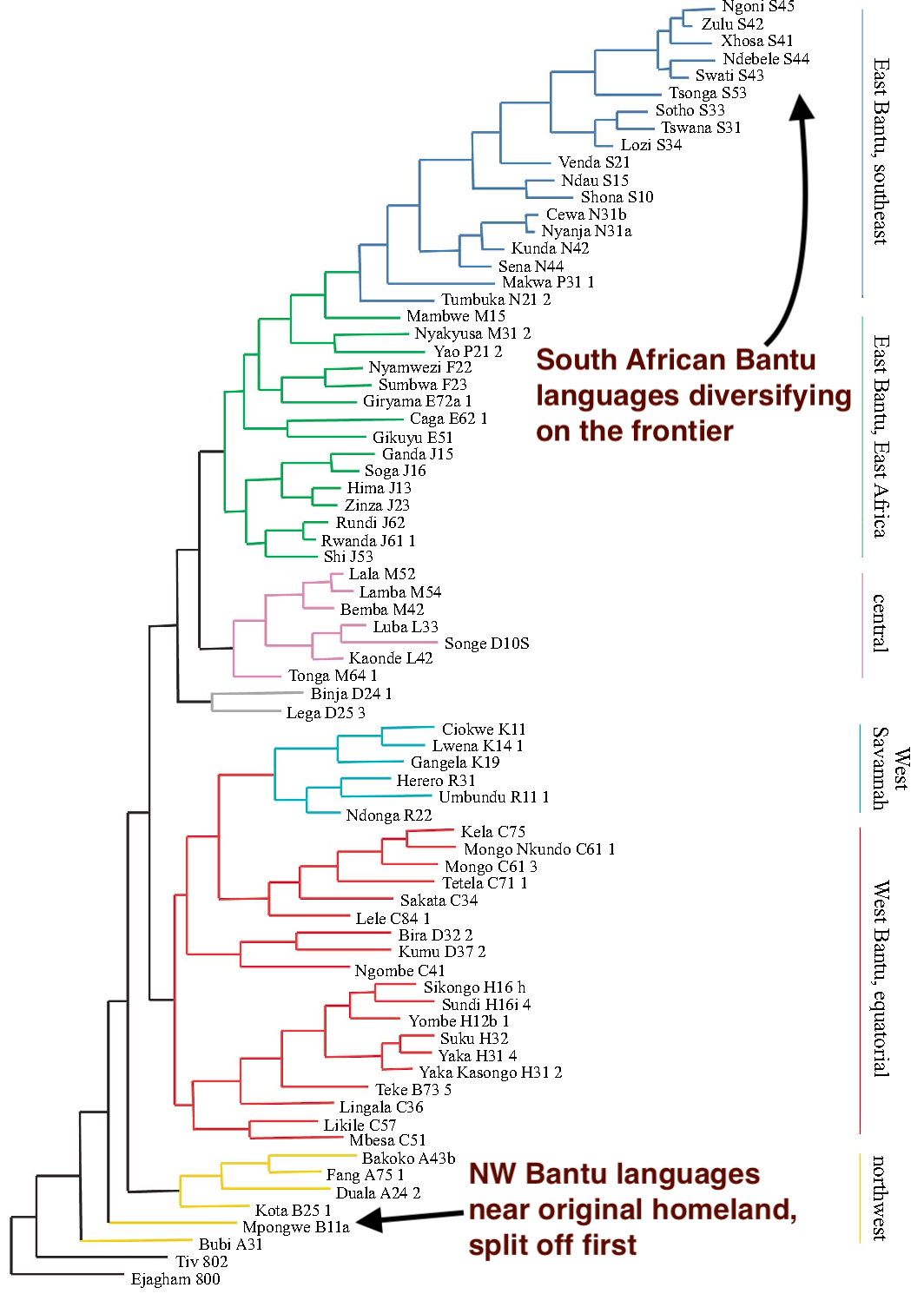

The Xhosa peregrinations were not unique, but a single chapter in a much larger narrative that began far to the north. They were just one of the innumerable tribes, ethnicities and nations that emerged from a millennia-old ethnocultural cauldron that boiled over, sending forth the phenomenon of the Bantu expansion, an agriculture-powered demographic revolution that reshaped the human geography of the entire African continent in the time between Sumer’s fall and Rome’s. The Xhosa’s 3,000-year and 3,000-mile-long trek from Central Africa began in the savannas flanking Lake Chad and initially swept slowly southward along the shores of the Atlantic, then shooting out to the Great Rift Valley and the Indian Ocean coastlands in a rapid burst, before finally flowing on to the cool highlands of the South African veld. The Xhosa encountered by the Boers were the westernmost of the Nguni-speakers, with waves of Zulu, Swazi and Ndebele following in their wake to their east. Because these nomadic clans were the leading edge of the final push to new territories, sure as a riptide, the indigenous Khoekhoe left an imprint on them, both in their language and genes. Though their interactions with the native peoples, who clung tenaciously to their last western strongholds right up until the Europeans’ 17th-century arrival, were often hostile, Khoekhoe heritage remains visible in the features of many Xhosa, including Mandela, a scion of a noble lineage. Khoekhoe influence also shows through in spoken Xhosa; almost 10% of Xhosa vocabulary contains telltale Khoekhoe clicks.

Nevertheless, despite this synthesis between newcomers and natives, when Bantu populations arrived at South Africa’s eastern edge 1,700 years ago, their conquests heralded the end of the old world of foragers and herders that at its height had dominated the continent from Table Mountain at the Cape of Good Hope to the foothills of the Ethiopian highlands. The Bantu brought iron weapons to battle, drove vast herds of cattle through which their elites measured their wealth, and had the know-how to cultivate sorghum and millet, carpeting southern and eastern Africa with peasant villages for the first time in the long history of human occupation there. It was only the startlingly novel biological environment of the Cape that finally brought the Xhosa march to a standstill. The region’s ecology was anomalous in Africa south of the equator. With cool rainy winters and hot dry summers, Bantu crops dependable elsewhere failed them. Below a line of latitude spanning the continent from Nigeria et al.’s Bight of Biafra to the Kenyan coastlands, by 1000 AD, only the Khoekhoe’s rangelands and the San’s deserts eluded Bantu domination of the entire continent’s span coast to coast. The San foragers continued to hunt and gather in the fastness of their deserts as they had for hundreds of thousands of years, while their cousins, the Khoekhoe pastoralists, successfully guarded their herds against the raiding Xhosa (and later fought off Dutch encroachments in the 17th century, before finally succumbing in the 1700’s).

And yet, despite dispersing across thousands of miles and occupying disparate regions of Africa for thousands of years, the Bantu remained culturally and biologically apart from earlier peoples in the regions they came to settle and rule. Even after a millennium of interaction between the Xhosa and their click-speaking neighbors, the Bantu tribes of South Africa retain much more in common with their linguistic cousins from East and Central Africa than the Khoekhoe and San with whom they share their land and recent history. Genetically, South African Xhosa are about seven times more distant from San foragers than they are from Bantu Kenyans, who live some 1,500 miles distant. Consider the Xhosa word for human: umntu, a cousin to the Kenyan Swahili mtu (the Xhosa’s Khoekhoe neighbors fittingly described humans as khoe). The word “Bantu” itself comes from the common root for “human” across these numerous languages, with the plural being abantu in South African Zulu, bana in Congolese Lingala, abantu in Burundian Rundi and watu in Kenyan Kamba

.