Applying IQ to IQ

Selecting for smarts is important

The holidays are upon us. By way of thanking all of you for being so willing to support my fledgling substack project, this week I'm releasing a little set of year-end mini-posts. These are five quick daily reads about the state as I see it of five sectors I follow. Might have been perfect for raising the level of chitchat at a normal year's run of December parties. In 2020, I hope they'll edify if it's not your field and that you'll let me know what I'm missing if it's your bailiwick I'm reflecting on.

Thank you for reading, for subscribing, and for forwarding to friends who you think might enjoy. A quick administrative note: I'll be adjusting my Substack price levels upward in the new year so now is a great time to grab a paid subscription if you've been considering. Or to use Substack's gift option while the prices are lowest. Cheers!

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Thinking Man

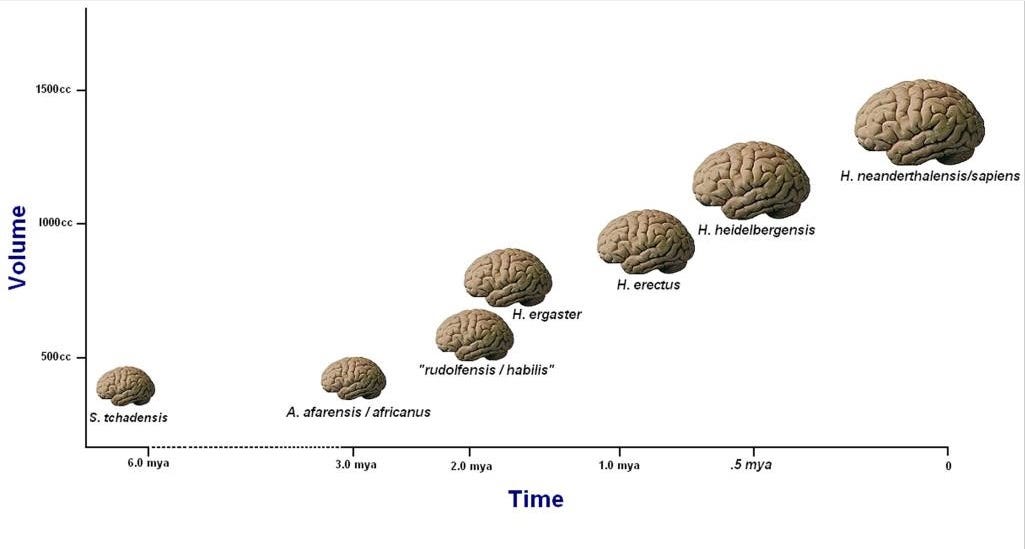

Homo sapiens are very smart. They are very smart because they have large brains. This is not controversial. In relation to our body size, humans have bulging craniums housing large brains. About 20% of our caloric intake feeds our brain when we’re resting even though it’s only 2% of our body weight. It’s a calorically expensive organ.

We were not always so large-brained. The fossils make it clear even to a non-specialist. Our brains began to grow several million years ago. There are many theories about why this might be, but the result is clearly that we have an extremely energetically expensive organ. So it must be useful. Evolution’s rule of thumb is “use it or lose it” if it’s imposing a cost. Just ask snakes where their legs are.

But all good things come to an end. Around 200,000 years ago the growth of our brains leveled off, probably due to biological constraints. The large head of the human fetus runs up against the limits of the mechanics of childbirth. Human infants are already born notably early in relation to their development. Natural selection tends to run into obstacles if it keeps being pushed in a single direction. Chickens grown huge for their meat eventually become infertile. And H. sapiens and its brain found its barrier 200,000 years ago. In fact, the largest brained humans seem to have lived during the Ice Age, not today. Since the transition to farming our brains have been shrinking.

Thinking about what?

The primary use of the brain is to cogitate. To think. But there are many ways to think about thinking. That’s why cognitive science and psychology are expansive disciplines. For example, there are a set of human competencies that derive from “hard-wired” and “innate” aptitudes. The human abilities to recognize faces, or throw a stone, are not purely environmentally learned skills. We are not born being able to recognize faces or throw stones. But, we learn to do these things very naturally and easily. Similarly, humans have a facility with spoken language which is clearly based on something peculiar about our cognitive hardware. Our brains. Again, we are not born speaking. Rather, it is something we are primed to acquire and learn easily due to the tools we are born with. Experiments with chimpanzees show that though they can take steps toward some vocabulary and syntax, even the youngest human toddlers are far superior in their linguistic abilities. We’re born that way.

Core competencies like language, facial recognition, and social intelligence are the mental characteristics that bind us and define us. All humans have language. Face blindness, the inability to recognize faces in a gestalt manner, is found in only a minority of humans. It is a genetic condition, as it runs in families. Very low social intelligence is often classified as “autism.”

Cultural innovations such as spears and swords spread rapidly and universally because the human ability to manipulate tools is universal. We may not have an instinct to grasp a spear, but we can learn how to do so naturally and without great difficulty.

This is not the case with all tasks. Most humans have difficulty understanding algebraic topology.

The Bright

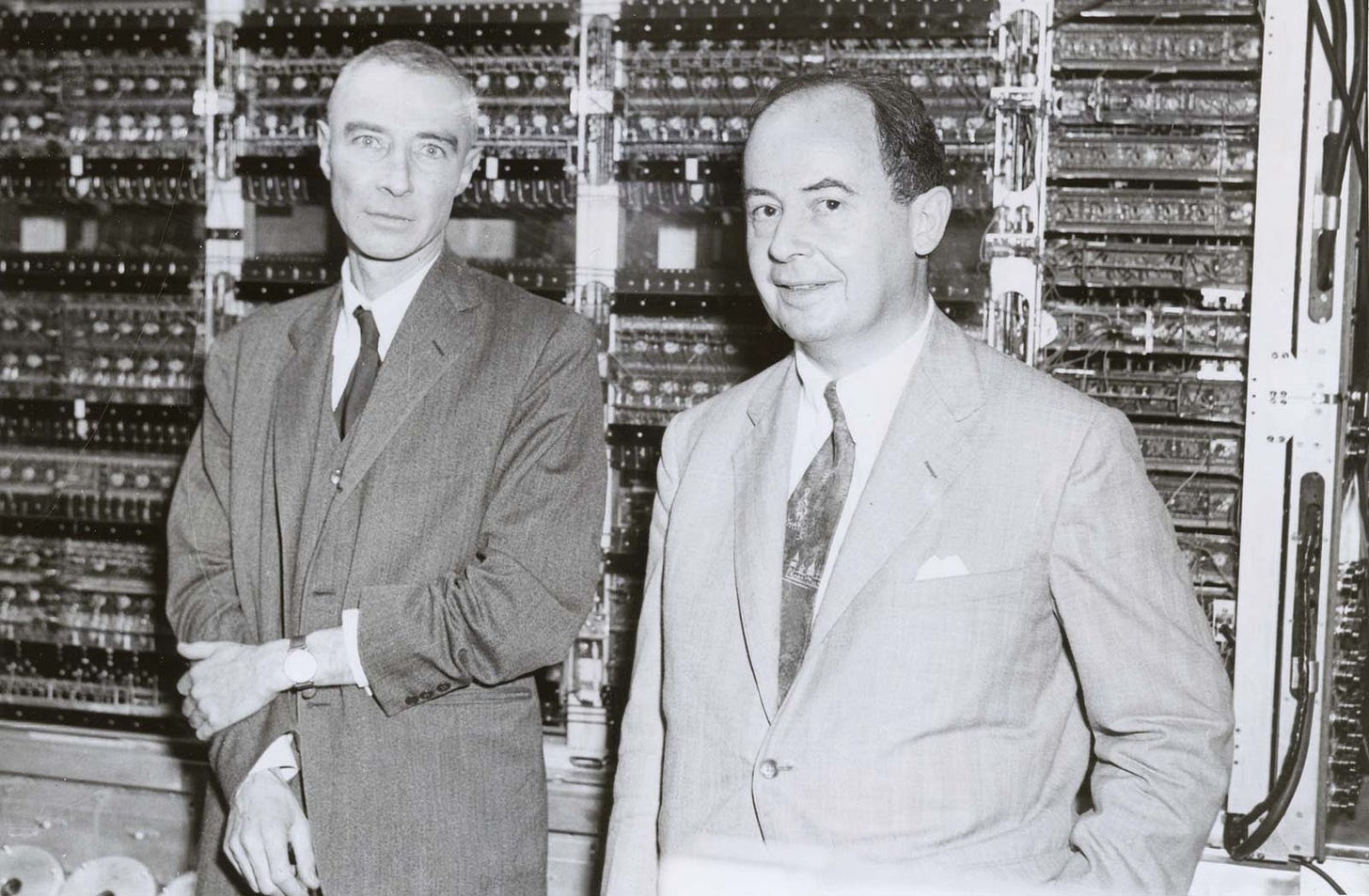

But there are also differences between people. Consider the polymath John von Neumann. A basis for the character of Dr. Strangelove, von Neumann was one of the most brilliant individuals of the 20th century. The theoretical physicist Edward Teller said of von Neumann that he “would carry on a conversation with my 3-year-old son, and the two of them would talk as equals, and I sometimes wondered if he used the same principle when he talked to the rest of us.” The founder of game theory, Oskar Morgenstern, has spoken of how his collaboration with von Neumann was incredibly fruitful for him, but for the latter game theory was a marginal contribution in relation to his broader oeuvre. It was said von Neumann derived proofs in an almost casual and instinctive manner that floored his intellectual contemporaries.

How do we explain von Neumann? Is such a mind the end of human evolutionary development?

No. He had one child, and today he has two grandchildren. The genes which led to the brilliance of von Neumann’s mind did not redound to his reproductive success, the only scoreboard in the game of evolution.

General Intelligence

Von Neumann lived to the age of 53. Here are some of the fields he contributed to: set theory, ergodic theory, operator theory, measure theory, lattice theory, von Neumann entropy, quantum mutual information, density matrix, von Neumann measurement scheme, quantum logic, game theory, mathematical economics, linear programming, mathematical statistics, fluid dynamics, cellular automata, DNA and the universal constructor. He was arguably the apotheosis of “general intelligence,” the ability to move fluidly between disciplines due to an innate mastery of abstraction and universal principles. In a stone-age society, someone of von Neumann’s caliber may have been unrecognized. His exceptional talents would not have found an expression in the world of flint blades. But embedded within a modern cultural matrix which leveraged his skills he became a supernova of intellectual creativity. Like Archimedes moving the earth with a lever, culture and civilization are the frameworks in which geniuses of von Neumann’s caliber can shine. Alone on an island, they are stranded with their thoughts, but poised in the matrix of civilization their explosions of brilliance shed a discernible light on all.

But obviously, there is a spectrum between von Neuman and the typical human. The human race is not divided between von Neumann and the rest of us. The ability to engage in deep and complex abstraction varies greatly amongst humans, along a normal distribution. The two giants of 20th-century mathematical population genetics are R. A. Fisher and Sewall Wright. Both were brilliant individuals who made incredible contributions to evolutionary biology. But Fisher was the more general thinker, making contributions to thermodynamics and statistics in addition to biology. Wright’s contributions to science were more domain-specific, and his mathematical skills generally understood to be of lesser caliber (Fisher trained formally as a child and young man in mathematics, while Wright trained himself as an adult).

Fisher was reputed to be personally rather unpleasant, and his extreme myopia as a child resulted in his need to make recourse to mental visualization of geometric problems due to his inability to see the chalkboard. Despite his mental brilliance, there is no suggestion that he was a genetic specimen of superiority. Outside of the context of late Victorian and early Edwardian England, it is likely that the young Fisher would be on the margins in the game of life. General intelligence in abstractions only matters in a society of specialization, where the division of labor continually deploys countless busy little platoons, each bustling about their abstruse tasks. In a world where everyone is a farmer or hunter Fisher would have struggled.

The common factor

In the early 20th century psychologists noticed that there was a correlation in performance across mental aptitude tests. Like any correlation this was imperfect, but the reality is that if you do very well or very poorly on mental aptitude tests, this pattern tends to reoccur across a series of tests. Those who do well on undergraduate admissions standardized tests tend to do well on graduate admissions standardized tests. Those who do poorly on one type of test tend to do poorly on another type. This is the general intelligence factor, a statistical construct that summarizes the positive correlation among standardized tests. It is what we colloquially refer to as the “intelligence quotient” or IQ.

This should not be surprising. There are many people who are athletic and excel at most any sport they try. It turns out that substantial muscle mass, fast reaction times, and a high level of coordination are useful across sports. This applies even at the highest levels. There are many athletes who are recruited for multiple professional sports leagues, and their choices are dictated often by utilitarian considerations (e.g., baseball careers tend to be much longer than football careers due to the higher rate of injury in the latter). Conversely, there are many individuals who do poorly at sports in general, due to low muscle mass and lack of coordination.

Because general intelligence does not manifest physically in the same manner that a fit physique does, it is often assumed that intelligence is purely a matter of internal effort. You can run a 100-yard dash with your time instantly displayed for every spectator to see. How well someone does on a two-hour pencil and paper test is at some remove from our immediate perception. Sometimes there is the expectation that if you work long enough you can derive a novel mathematical proof. Would we ask the same of an average height and athleticism person when it comes to dunking a basketball? Even the most brilliant math majors often fail to solve any questions for the elite collegiate Putnam competition. There are limits to how far effort can take you.

IQ matters

General intelligence is one of the most predictive psychological measures in existence. The chestnut of wisdom that ability to test well measures how well you take a test is true but trivial. The implication that test measurement does not correlate with other aspects of performance is manifestly false. Those with higher measured IQs have higher incomes, greater educational attainment, and lower crime rates (this remains true among siblings who differ in IQ). This is well known within psychological science, but for various reasons has been obscured and downplayed by broader American culture.

As with the athletically gifted, the differences in outcomes is most obvious in those who are intellectually gifted at a young age. The chart below shows the outcomes of 259 children identified as very gifted in their early teens on the SAT:

One out of thirteen of these extremely bright children became tenured professors. One out of thirty-three wrote a book. Nearly half obtained doctorates. These are not average kids who simply “test well.” There is luck in life, but the die is loaded. Very high intelligence is no guarantee of exceptional achievement, but it clearly changes the probabilities.

The correlations for IQ and socially relevant variables can be quite modest. For example, some studies find correlations between childhood IQ and income as an adult to be 0.40. One interpretation of this is that “IQ doesn’t matter,” after all, there are many well-off people with lower IQs and many poor people with higher IQs. Most of us know cases like this, so intuitively the idea that IQ matters such a great deal in life outcomes strikes many as implausible. There are many ways to become well-off. And, no matter your IQ, if you are a disagreeable person with low conscientiousness your chance of success is often quite low.

And as with athletics, hard work can get you only so far as you move up the ladder of achievement. At 5’5 Sarah Palin has talked about how she was a successful high school basketball player not due to any particular talent. Rather, she just worked very hard. But that only got her so far. At each stage the athletes are more unique and exceptional physical specimens, endowed with both physical talents and harder-to-define cognitive abilities maximizing coordination and skill. There are many tall human beings, but very few can be elite basketball players, because these athletes combine great size with a grace and coordination that tall humans often lack. Michael Jordan’s fluid movements were not typical for a man of 6’6. In this, he exceeded even his peers in the NBA, who often seemed ungainly next to “His Airness.”

It is quite plausible that one can obtain a university degree through conscientiousness despite modest cognitive aptitudes. There are many such individuals. But who is going to win a Fields Medal in mathematics, which recognizes the most brilliant young minds? A high IQ is not sufficient in this case. Not at all. But it is probably necessary.

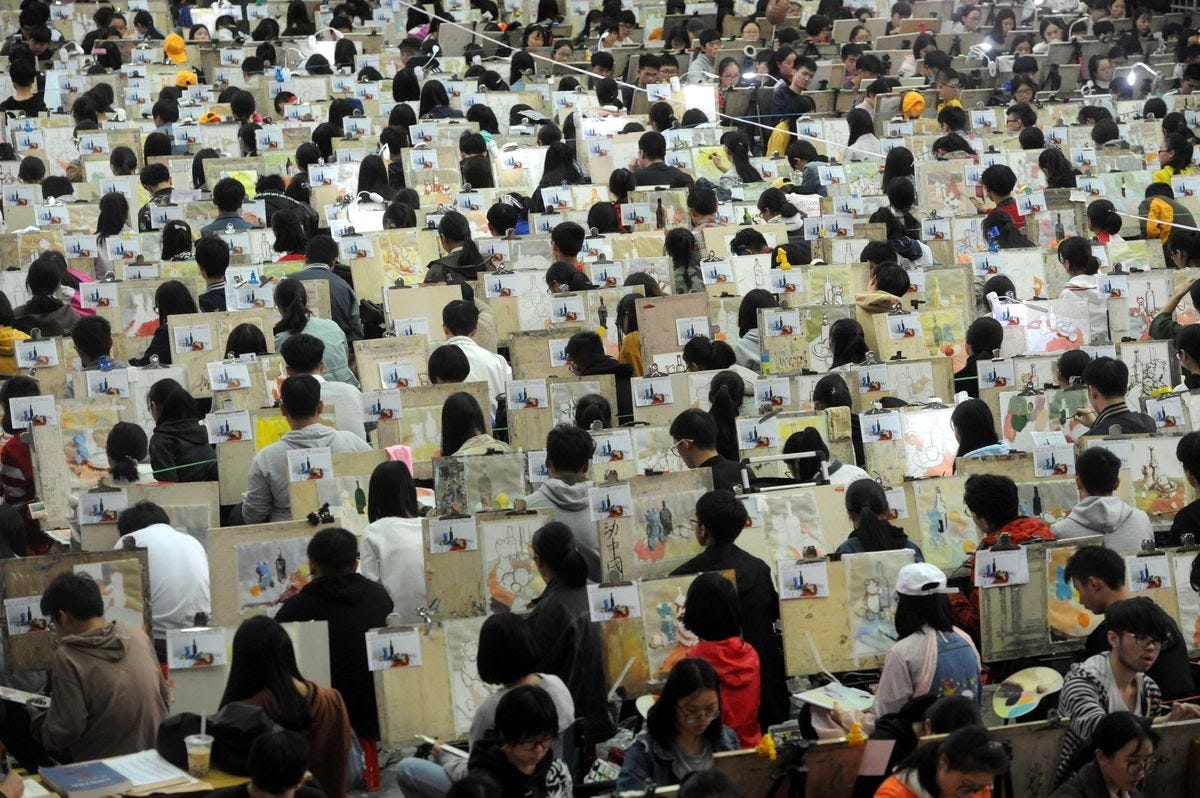

Testing has been with us for 2,000 years

In various forms, standardized testing has been with us for 2,000 years. During the Han Dynasty a group of bureaucrats began to undergo examinations to vet their competency. This system of examinations became more formalized and elaborated in later dynasties. The rationale for these examinations was that those who rule should be inculcated in timeless values and exhibit intellectual abilities. While China’s gentry mastered the classics to obtain high office, the West’s elite saw education mostly as a status marker and an avenue to elite cohesion. Roman aristocrats like Quintus Aurelius Symmachus peppered their letters with literary allusions to mark themselves as noble-born. The fall of Rome corresponded with the decline in the prestige of elite education, and the rise of a purely hereditary nobility, aided by the Christian Church. They ruled at the point of a sword and their legitimacy was their lineage.

But the age of aristocracy ended in Europe, and a new egalitarian ethos required ways to identify those with talent but no connections or pedigree. Intelligence testing appeared in modern Europe as a way in which to identify talented individuals born outside of the elite. Today the French elite is selected in large part through admissions tests to the grandes écoles. While Prince Charles attended Cambridge, his son William, who was reputedly academically stronger than his father, attended the less prestigious University of St. Andrews. Though universities remain bastions of the elite, deploying standardized testing frameworks usually slows the stream of connected but technically underqualified elites jumping the queue. George W. Bush went to Yale. His younger, more intelligent, brother Jeb attended the University of Texas in Austin. The older Bush was admitted before the meritocratic revolution in admissions which opened up Yale to many more outside of the old WASP ascendancy.

The long Chinese history of testing prefigures many of the arguments we have today about intelligence and how to measure it. Because the learning necessary to sit for the examination required leisure, elite lineages often invested in bright young men, subsidizing their schooling and promoting them forward. Sometimes whole lineages would support a promising candidate. This caused great distress when failure was the ultimate outcome. In the 19th century the failed candidate Hong Xiuquan went insane, and eventually became the prophet who triggered the Taiping Rebellion in which millions died. Remember, Hong’s failure squandered years of collective investment of resources by his whole extended family. Obviously the resources necessary to study mean that the privileged would be at an advantage, but the reality is that even among the privileged, to even be allowed to sit for the examination one had to have some talent. Additionally, throughout Chinese history, there were instances of men of very modest means rising to eminence on account of their pure incandescent brilliance. In a similar manner, the Indian genius Srinivasa Ramanujan lacked resources and access to the latest books, so he re-derived portions of Western mathematics. His Cambridge mentors immediately recognized his brilliance and sponsored his research fellowship.

When examinations fell out of favor, as occurred during the Eastern Han, the Tang, and the Yuan, the consequences were inevitable. A coterie of great families, or ruling castes, came to dominate the administration, and unattached youth of talent were excluded and marginalized. The testing regime was uniformly disliked by the aristocrats because they already had power, connections, and polish. They perceived in themselves the right to rule. They required no test to validate their self-worth. For those born to rule, the memorization of ancient texts and the drafting of learned essays is tedious. But to the bright but unconnected, mental gymnastics are a chance to demonstrate their worthiness.

Sometimes the historical precedents are eerie. The Age of Confucian Rule recorded that there was a tacit understanding that there would be a ceiling on the number of officials who came out of Fujian. This southeastern coastal province brimmed with scholarly activity during this period, and it sent far too many candidates through the examination system for ruling elite comfort. The Song engaged in what we would call affirmative action to allow for the representation of Northern officials within the bureaucracy.

The return of privilege

The coronavirus pandemic has now presented some opportunities to remove testing from American life. One of the major-specific reasons cited is long-term racial discrepancies in average score. The more general objection is that standardized testing favors the privileged due to the cost of the tests, as well as the reality that those from higher socioeconomic backgrounds tend to be more well prepared to take these tests. This is almost certainly true on some level, though the success of the children of poor Bangladeshi immigrants in New York City shows the meritocratic path that testing can provide.

Tests are imperfect. But what is the alternative? Over the past few years graduate schools have been removing the GRE as a requirement for admission. What will the consequence be? If the history of China is any guide, those with connections and pedigree will benefit. Without a hard-to-fake entrance exam, recommendations from those you trust will loom large again. The abolition of the GRE will be a back door through which the “letter of introduction” returns. Who will be hurt by this? Who will benefit? There are many answers here, but one thing seems obvious: those without connections will suffer. International students. Those from working-class backgrounds. Non-traditional older students trying to turn their life around with the benefit of hindsight. When academics rely on networks of those they already know, the circle of inclusion will begin to narrow. Ironically, attempts to “foster inclusion” by removing standardized testing will inevitably constrict the space of those included.

Genes, IQ, and Family

Depending on the study IQ is at least 50% heritable. That means that half the variation in IQ in the population is due to variation in genes. Through genomics, scientists are now accounting for this through DNA as well as correlations across relatives. Pure genetic predictors of IQ can now explain life outcomes like how many years of education you complete. Over the next few years the genetic predictors are likely to get better, and the relationship between class, genetics, and education will become clearer. What the genetic results tell us is that there are children with a likely aptitude who nevertheless forgo university due to their class deprivation. Conversely, there are well-off children without aptitude who do go to university.

Genetics and IQ are separate topics and domains, but due to the heritable component of intelligence, they are often connected. The conflation of genetics and IQ makes the latter far more radioactive. If the consequence of this conflation is that both intelligence and achievement testing disappear, then the outcomes may surprise people. Human judgment matters, but cold and cool rules are better at sorting competent from incompetent.

The West’s Last Test

In a strange denouement, the professional-managerial class of the United States, itself sorted through grades and standardized tests, has turned against these sorting tools of the institutions which provide them prestige and power. When scientists assert that the GRE does not predict success, they magically forget the ability of range restriction to constrain the predictive power of a variable. Believe it or not, taller basketball players are not the best basketball players in the NBA. That’s because NBA players are all already tall, more or less. The abolition of the GRE and marginalization of the SAT, amount to a massive natural experiment. These experiments are predicated on the idea that standardized testing is useless. No matter that in various forms this method has been around for 2,000 years, and we have evidence of the benefits and deficiencies of testing in the historical record. Close your eyes and believe.

Meanwhile, the Chinese and other Asian nations continue to use standardized tests as a mechanism for admission and sorting. This does not guarantee better leaders necessarily, but it does mean that members of the professional class have all gone through the same mechanism of selection, and one which is relatively insulated from the impact of pedigree and connection, which otherwise loom large in many Asian societies. The fact of the importance of connections means that Asians understand the value and power of the “big test” which is blind to all the other “holistic” factors, which often smuggle privilege in through the back door.

The next generation will be a test. Will America turn away from intelligence and aptitude testing to unleash untapped capital? Or will our society’s meliorist impulses only usher in a new era of cronyism and favoritism? History teaches us to anticipate the latter. But you never know until you run the experiment.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Thank you again for reading, for subscribing and for forwarding to friends who you think might enjoy. A quick administrative note: I'll be adjusting my Substack price levels upward in the new year so now is a great time to grab a paid subscription if you've been considering. Or to use Substack's gift option while the prices are lowest. Cheers!

What I am saying might sound silly. But I am born and raised in India. Our culture has always given utmost importance to grades. In fact, we overdo it. But now at the age of 40 facing one of the worst times of my life as a small business owner (thanks to COVID), I feel that no matter what happens at least I have my degree and my education with me. When I read the last part of your post I can't help but ask this question to you, does the west have a death wish? If one removes grades as a measurement criterion what else is left? I do not mean to say it should be the only factor, but it has to figure in the matrix somewhere right?

Good post!

Re "Around 200,000 years ago the growth of our brains leveled off, probably due to biological constraints. The large head of the human fetus runs up against the limits of the mechanics of childbirth."

I think most now believe the 1960s birth canal limitation idea is false, eg

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/27/health/birth-canals-evolution.html

Even wikipedia is pretty up to date on it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Obstetrical_dilemma#Obstetrical_dilemma_revisited

Re the broader first sentence, I think the idea of biological constraints on brain has no data backing it. It's a flattering intuition for smart people to hold. So it never dies. If true, it would imply that there is a natural upper limit to IQ, and the breeders equation does not hold in the upward direction. Which is of course false. The obvious answer is an energy consuming brain is a trade off, and bigger brained people started having fewer children since 200k years ago, as the trade off hit the balance point. Which has plenty of evidence through all known human history, and plenty of data shows it applies right now in spades throughout the world. Also, consider Cochran et al 2006 paper. Must be false since breeder equation can't work due to these never stated mysterious biological constraints that don't exist. Gregory Clark also must be wrong too by the way. It's like being too tall. Evolution can always evolve to be a bit taller if selection favors it. It just selects until it's balanced against something. Often energy constraints. But for a cooperative hypersocial species, social selection constraints as well. Just not biological.