Among Afghans: jewel of the dragon

People of the crossroads

During August’s shambolic withdrawal from Afghanistan, CNN commentator Fareed Zakaria noted that there were nascent worries among conservatives about the influx of refugees from Afghanistan. He characterized them as saying of Biden, “he's trying to get brown people to come into the country." Obviously, “brown” here is shorthand for a foreign and exotic group that practices Islam. But the reality is that people from Afghanistan are quite diverse in their physical appearance, and many of them, like the Nuristani man pictured, given a couple of sartorial tweaks, could easily pass for a white European. This is why Westerners in the country who wish to “pass” as Afghans are told to pretend they’re Nuristani, and that they don’t know Pashto or Dari, the two majority languages in the country.

Nuristan is an out-of-the-way region of Afghanistan, nestled up against the border with Pakistan. In the 19th century, it was called Kafiristan, because its pagan people were not Muslim, kafir being a pejorative term for non-Muslims. Rudyard Kipling’s 1888 The Man Who Would Be King was set in Kafiristan. Eight years after the book was published, the Emir of Afghanistan conquered the Kafirs and forcibly converted them to Islam. Their land was renamed Nuristan, and they are most well known today for their relatively fair-skinned appearance, just as they were already in the 19th century. Kipling’s novel was squarely in the “lost peoples” genre so popular in the 19th and early 20th centuries when isolated areas unknown to Europeans remained to be discovered, but it also explored the fact that racial affinities did not always lead to cultural comprehension. The protagonists of the novel observe that the Kafirs were blonde:

...men with bows and arrows ran down that valley, chasing twenty men with bows and arrows...They were fair men - fairer than you or me [the British protagonists] - with yellow hair…

One of the British adventurers notes that the Kafirs were “so hairy and white and fair it was just [like] shaking hands with old friends.” And yet appearances can be deceptive. The Kafirs were pagan idol worshippers, whose culture was riven with superstitions entirely alien to Kipling’s European protagonists.

Though it seems unlikely that American bureaucrats are familiar with Kipling, individuals from Afghanistan are classified as white under the US-Census racial categories, in keeping with the status of other ethnicities from the Middle East and North Africa. Bizarrely, a Pathan from Pakistan is an “Asian American,” while a Pashtun from just across the border is “white” (Pathan is simply the term for Pashtun in India and Pakistan), despite the two groups being nearly genetically indistinguishable.

And yet obviously, many Afghans do not fit the image most Americans summon when told someone is “white.” Perhaps one of the more striking cases is the erstwhile Afghan warlord Rashid Dostum:

Dostum is an ethnic Uzbek from the north of Afghanistan, a small minority that has nevertheless been very influential due to his role as one of the top three political and military figures in the country for four decades. They are a Turkic-speaking group for whom the nation of Uzbekistan is named, and an essential part of the complex ethnographic tapestry of Afghanistan. Though Afghanistan has not conducted a proper census in decades, most observers believe the Pashtuns to be the most numerous ethno-linguistic group in the nation. Though there are three times as many Pashtuns to the east in Pakistan, the smaller faction within the country have traditionally ruled Afghanistan, and the term Afghan as an ethnic label is often used synonymously with Pashtun.

Afghanistan’s second-most prominent group is the Tajiks. Like Uzbeks and Pathans, this is an ethnic group that sprawls across multiple national borders. But whereas there are more Uzbeks and Pathans in Uzbekistan and Pakistan, there are actually many more Tajiks in Afghanistan than in Tajikistan. Like Pashtuns, the Tajiks speak an Iranian language, a Persian dialect, Dari. In comparison to Pashtuns, Tajiks have a more urbane and northward focus, being part of Greater Central Asia.

The last major ethnic group of Afghanistan are the Hazara. Like the Tajiks they speak Dari, and like the Uzbeks, they exhibit an East Asian appearance. But unlike most Afghans, they are invariably Shia Muslims, rather than Sunnis. And finally, rounding out the ethnic mix of Afghanistan, are numerous smaller groups like Nuristanis, Baloch and Brahui.

This rich ethno-linguistic complexity is the outcome of thousands of years at the crossroads of Asia. Afghanistan may seem out of the way, but its mountains and valleys were traveled by missionaries, migrants and merchants, taking Islam north, bringing Turks and Mongols south, and facilitating interaction between India, Iran, and the Arab world.

At a cultural crossroads

Situated in a rugged and mountainous upland to the west of Tibet, Afghanistan has managed to both retain an exotic isolation, and remain enduringly at the center of geopolitical machinations. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the independent Emirate of Afghanistan found itself a pawn in the Great Game between the Russian and British Empires, as the two powers challenged each other over trade routes and warm-water ports in the heart of Asia. For some decades in the 20th century, Afghanistan experienced an idyllic period of peace under its last king, the playboy Mohammed Zahir Shah. But that was shattered in the 1970’s with his overthrow, and the nation was soon torn between the Soviet bloc and the Western powers. The Afghan civil war of the 1980’s, which ended in Soviet defeat and withdrawal, and then the fall of the subsequent Soviet-backed regime in the early 1990’s, gave way to the civil war of the 1990’s, which culminated in Taliban victory. By the 21st century, in the wake of 9/11, Afghanistan again became a catspaw in American geopolitics.

But this rugged region of southern Central Asia wasn’t always simply the backdrop to civil war and conflict. During the Bronze Age, more than 4,000 years ago, the mountains of Afghanistan yielded precious lapis lazuli and essential tin. Lapis lazuli is a beautiful blue mineral stone that can be shaped into exquisite ornaments. The famous rediscovered burial site of the Queen of Ur contained a lapis lazuli-encrusted bull’s head. But to obtain it, the Sumerians had had to import it through a variety of intermediaries from its original source in Afghanistan, just like raw amber slowly progressed from the north to the south.

Unlike luxurious lapis lazuli, tin was essential. Bronze is an alloy of tin and copper, and while the latter was found close at hand in Cyprus, the tin component required by ancient civilizations of the Near East often came from Afghanistan. These sorts of natural resources are the reason that Bronze-Age Afghanistan seems to have been dotted with trading colonies from the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), which flourished to its south and east, in modern-day Pakistan. In a strange prefigurement of the present, the more populous societies to Afghanistan’s south and east seem to have always taken an interest in controlling its resources and leveraging its geopolitical importance.

We do not know much about the ancient people of Afghanistan who mined tin and collected lapis lazuli were. But it is certain that genetically, the ancient Afghans were quite distinct from any group in the region today. 12,000 years ago, with the adoption of agriculture, the unique and diverse societies of West Asia began to expand from their core hearths and mix with each other through trade and migration. People in the Zagros mountains of western Iran migrated west, to the Mediterranean, while societies on the Mediterranean coast sent outriders eastward along the northern fringe of the Fertile Crescent. The mixed population that emerged by the Bronze Age still defines West Asia today, but the heritage of the ancient people of Afghanistan was far less touched by the great amalgamation. Rather, ancient southern Central Asians who occupied what was to become Afghanistan reflected migrations out of the west at the end of the last Ice Age. Additionally, these people absorbed a trickle of Siberians migrating out of the north, via the highlands to the east of the Central Asian deserts, as the Turks would do in later millennia. Humans are mobile and protean, but the landscape across which they move is far more fixed, imposing constraints even across the millennia.

Today the primary languages in Afghanistan are Iranian. We now know that the genetic signatures associated with Iranian peoples, in particular the Y-chromosomal lineage R1a1a, first appear in Central Asia 4,000 years ago, in Khorasan, at the border of northern Iran and Afghanistan. It took another 1,000 years for them to percolate south and west, until they reached the fringe of Mesopotamia and came to the attention of the Assyrians in the 8th century BC. Fars, the heart of historic Persia in the southwest, did not come under the rule of Iranians until a century later.

Far to the northeast, in modern Afghanistan, Iranian-speaking tribes had likely been ascendent for over 1,000 years by the time the Persians rose to power. It was in the former area that the oldest part of the holy scriptures of the Zoroastrians, the Gathas, was composed. The ancient Iranian language of the Gathas, Avestan, bears more similarities to the Sanskrit of the Indian Vedas than it does to Old Persian. The eastern Iranians were very different from the ancient Persians, and the spread of Persian culture into Central Asia, and its adoption by the Tajiks, occurred during the Islamic period, rather than being native to the area.

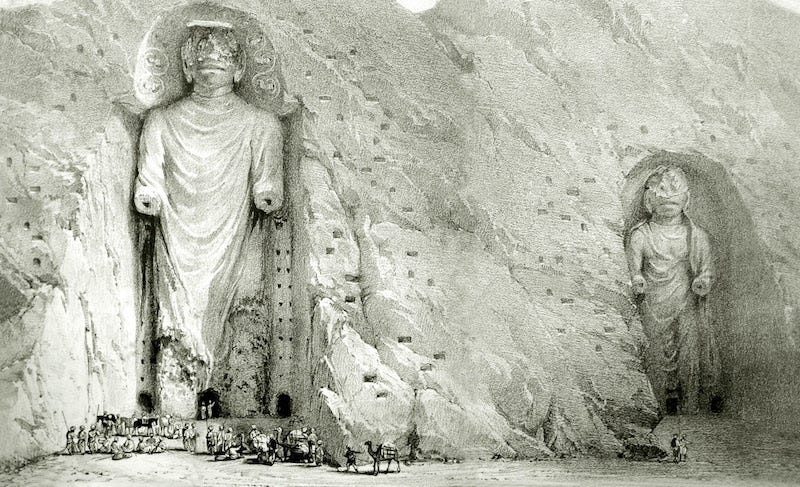

When Alexander the Great conquered the lands of what became Afghanistan, they were seen as a rough frontier territory, inhabited by Iranian tribes that would only later give rise to the Pashtuns and Tajiks. After the fall of Alexander’s empire, it was here that a redoubt of Greeks maintained a kingdom in Bactria for nearly three centuries. The Afghan city known as Bagram, host to the erstwhile American airbase, was originally named Alexandria. Though its patron god was the Greek Zeus, Alexandria was better known for its monasteries with thousands of Buddhist monks. Afghanistan again played a role at the crossroads during this period, as the Greco-Bactrian Buddhists contributed cultural innovations like fine statuary depicting the Buddha. They then transmitted this innovation of the faith onward to the east into China 2,000 years ago, where Buddhist statuary mutated again.

Sons of the Conquerors

After 200 AD, the great Eurasian steppe began to reverse its historical migratory pattern. Whereas earlier, many Indo-Iranian people had moved from the west to the east, in the centuries after, Siberian Turks began to flood westward. By 665 AD, as the pre-Islamic Sassanian Persians to the west were being conquered by the Arabs, to the east, Kabul fell under the control of the Turk Shahi dynasty. Though newcomers, like the Greco-Bactrians they were enthusiastic adopters of local religions and traditions, in particular Buddhism. The later phases of the construction and development of the Bamiyan Buddhas date to the Turk Shahi and their patronage. For two centuries, they engaged in a war of attrition against the Arab Muslims to the west. As Islam began to gain traction in Central Asia in the north and in Iran in the west, the region around Kabul remained steadfastly Buddhist. Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road documents the century or so when, cheek by jowl, Buddhist monasteries, and Islamic mosques clustered along the same trade routes, as Christians, Muslims, Zoroastrians and Hindus traversed Eurasia.

In the early 9th century, the Turk Shahi were defeated by the Arabs and converted to Islam after their great golden Buddha idol was taken to be displayed in Mecca as a sign of their submission. Turned into puppets by the Arab Muslims, they were overthrown by their Indian Hindu prime ministers, who then ruled as the Hindu Shahi dynasty, with their name pointing to their southeastern origin. They promoted their religion and culture in Afghanistan for a century, highlighting that the region’s geography made its connection to South Asia inevitable. In its turn, the Hindu Shahi dynasty was expelled from Kabul, defeated by Turks who had adopted Islam.

It was with the rise of Mahmud of Ghazni, one of these Muslim Turks that were to shape later history across Asia, that Afghanistan moved from being a frontier boundary between civilizations to becoming the heart of eastern Islam. Mahmud raided deep into India, while also pushing north into Central Asia and west into Iran. His capital, Ghazni, was located exactly between modern Kandahar and Kabul, astride the modern road between the two cities. By the end of his life, Mahmud’s domains included much of Iran, Pakistan, as well as the former Soviet republics of Central Asia. His writ ran from the Indian Ocean to the Aral Sea. Though the Turk son of a slave soldier, Mahmud patronized the great Persian poet Ferdowsi, as well as the polymath al-Biruni, the latter of whom wrote one of the first anthropological treatises on India. Despite a bloodthirsty reputation in India, he encouraged the flowering of the multicultural civilization of eastern Islam, where Turkic rulers encouraged Persian poetry and Indian astrology.

The ethnic complexity of modern Afghanistan was already present by the time of Mahmud, as he ruled a mostly tribal Iranian-speaking populace, the ancestors of the modern Pashtuns, despite being a Turk who patronized urban Persian culture.

At a genetic crossroads

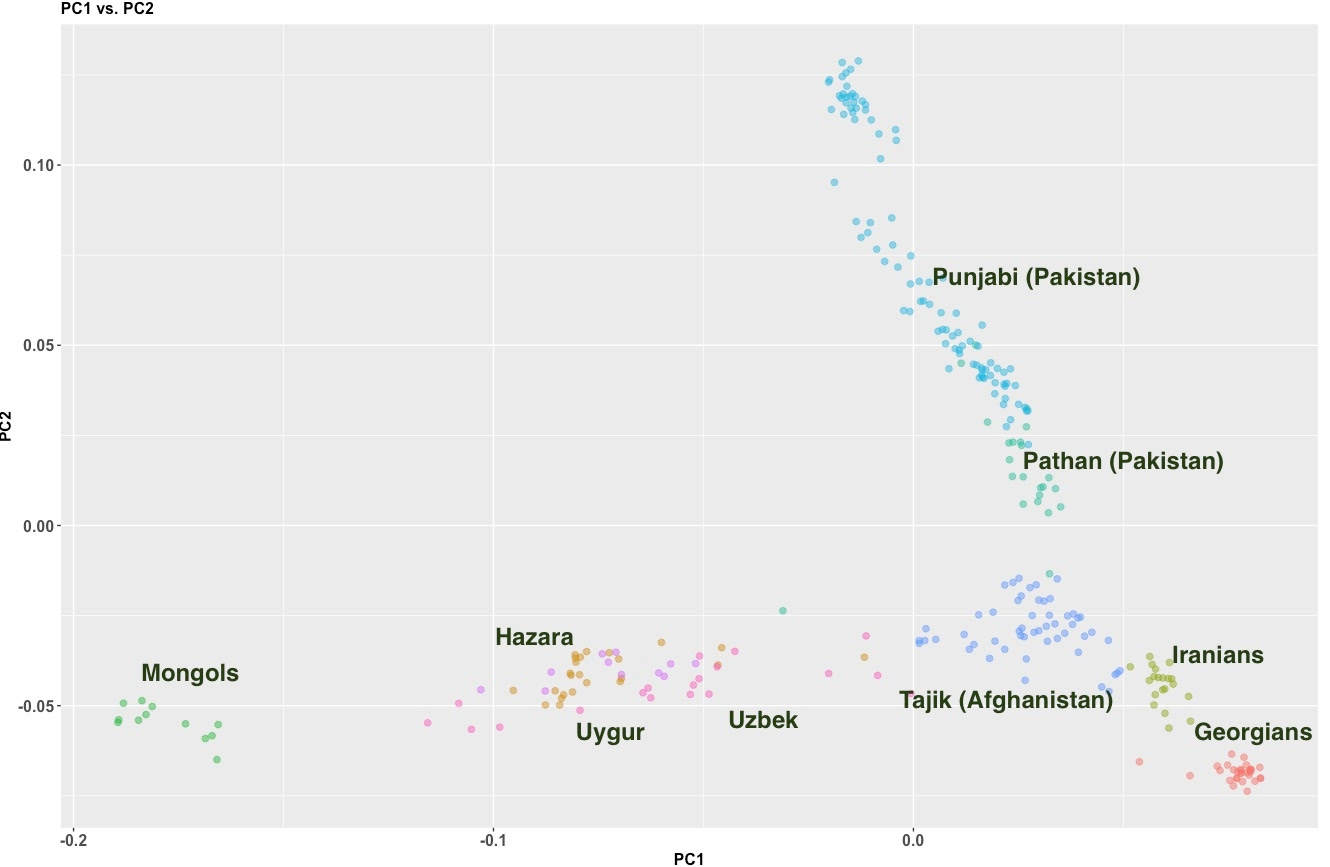

The above principal component analysis visualizes genetic variation within the data and illustrates how related various ethnic groups in Afghanistan are to each other, and to other world populations. The x-axis is clearly defined by the east-to-west gradient in genetic ancestry within Eurasia. The y-axis, meanwhile, measures how groups are related to South Asians. Among groups in Afghanistan, Hazaras and Uygurs are the most east-shifted, while Pathans are most like South Asians. Though the Tajiks are more distinct from South Asians than Pathans, their relative closeness compared to Iranians points to the deep connections between the Indian subcontinent and Central Asia that goes back to prehistory, from the contacts between the IVC in northwest India and the Oxus civilization, just north of Afghanistan, to the migration of the Indo-Aryans out of the northwest.

The primary finding from genetics is that the Iranian-speaking peoples of Afghanistan: Pathan and Tajik, are not so different from one another. This confirms earlier work that Pashtun, Pathan, and Tajik are all clustered together. Though the Pashtun speak rustic dialects, and the Tajik may make their way in cultured Persian, ancestrally the two groups come out of the same medley of ancient tribes that Alexander the Great encountered more than 2,000 years ago. But while the Pashtuns remain wedded to their village-based lifestyle, riven by fractious clans, the Tajiks and their ancestors were swept up in the broader currents of the Silk Road, abandoning their native Iranian dialects in favor of Persian, and losing their tribal identities as they went. The Tajiks have also interacted more closely with Turkic people who came to dominate the regions to the north of Afghanistan, so they show much more affinity to East Asians than the Pashtuns do.

The cases of the Uzbeks and Hazaras, the two other major ethnic groups in Afghanistan, are more curious. Though Uzbeks are Turkic, and their ethnic name comes from the Uzbeg, a descendent of Genghis Khan, their origins are a mix of diverse Turkic and Iranian strains. Across Central Asia, Uzbeks and Tajiks know each other’s languages and intermarry extensively. The emergence of the Hazara is a more historically specific phenomenon. Though they speak Dari like Tajiks, the Hazara are visibly East Asian, and often subject to discrimination on that basis in Afghanistan. In addition, confessionally, they are Shia Muslims, like the Iranians to their west. The traditional legend was always that the Hazara descended from Mongol soldiers fleeing Iran after the collapse of their regime there. Today we know this is almost certainly true, as the Hazara men usually carry the Y-chromosomal lineage of Genghis Khan.

The Turkic and Mongol connections of the Hazaras and Uzbeks, and even of some Pathan and Tajik, hints at the critical role of geography in Afghan history. Though the archaeological details remain to be worked out, as I observed above, ancient Siberians seem to have mixed with the native prehistoric Iranians in Afghanistan sometime between five and ten thousand years ago. How did these Siberians encounter the early Central Asians? Likely the fertile hills in the shadow of the Tian Shan played a role, serving as a conduit for hunter-gatherers and pastoralists alike. After these Siberians, it seems likely that the early Indo-Iranians also used the same elevated highway to move south from the Altai and the Kazakh steppe. In their turn, the historical Turks also moved southward along these mountains.

Though history is protean, geography is fixed.

A microcosm

The average age in Afghanistan is 18, and the average lifespan 65. It is a poor country that has been torn apart by violence and characterized by endemic illiteracy and religious fanaticism. But our misgivings about the state of Afghanistan today tend to color our view of the region or the nation and leave us at risk of mistakenly thinking chaos is its eternal state. Afghanistan is heir to a rich cultural history that has been surprisingly well recorded. At the time the ancestors of the Pashtuns were fighting and allying with Alexander the Great, the Romans and Greeks were vague as to who might even live in misty Britain. The region’s diverse history means that today there are modern Afghans who could comfortably mingle with the throngs on the streets of New Delhi, Stockholm, and Beijing, without anyone batting an eye. Though the US Census classes Afghans as white, they’re actually the microcosm for much of Eurasia, as so much of the world’s history has coursed through and out of their ancestral domains. Afghanistan is not just where empires go to die, but where empires were born and nourished.

Today Afghanistan is widely seen as shorthand for basket-case. The Taliban, an offshoot of the fundamentalist Deobandi religious movement, whose origins are in India, are quite literally medieval in their aims. And yet on a deep level, they are likely to fail because their goal is to flatten and homogenize, and the very geography of Afghanistan bristles at this. Powered by the Pashtun tribes, the Taliban can never succeed, if the Pashtuns’ history itself is any indicator: they themselves bear testament to an eternal resistance against flattening and assimilation. Despite thousands of years situated between India and Iran, the Pashtuns remain distinct in their language and self-identity, never becoming Persian or Indian (though the Prime Minister of Pakistan is a Pathan). Similarly, Afghanistan will remain a diverse land with many people and stunning vistas. It will remain a geopolitical crossroads and its isolated mountains will continue to yield exotic tribes and strange beliefs alien to the broader world deep into this century. The Taliban will ultimately fail in their attempt to rationalize and dominate, just as all others have.

This is perhaps difficult to understand if all you know of Afghanistan comes from the international media, ensconced as it is in “green zones” and protected enclaves. But Afghanistan is a vast and rugged land the size of Texas, poorly mapped and charted, where half the population is illiterate, and modern communication technology penetrates spottily when at all. It is still a Bronze-Age society lightly dotted with 21st-century cities. To underscore this, let me finish by excerpting an email from a correspondent, a former officer in the American military:

A dozen years ago, I was working along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border with some Pashtun Afghans officers who told me a story of a militant fighter they had captured right after the 2001 invasion who came from an isolated valley along the Pak-Afghan border. This man, along with his tribe, believed the sun is a jewel vomited by a dragon each morning and then swallowed by that same dragon again on the other side of the world each night after the dragon has rushed under the (presumably flat) earth all day to catch it. The man explained he was fighting because he had learned that the Germans had invaded Afghanistan to steal the jewel, and he needed to stop them or the world would be plunged into darkness.

The Afghans with whom I spoke were also from the border region, and they had never heard of such a belief from anyone else. They were confident the man did truly believe what he was saying and noted the man was a Pashtun Sunni and not Hazara, Nuristani, Kalash or Shia, groups whom these Pashtun Sunni officers considered variously odd.

...

The Afghans I worked with considered the casual conflation of Brits/Russians/Americans among local tribesmen to be merely amusing, but even they were quite taken aback by what they recognized to be the clear survival of a pre-Islamic dragon myth in a very isolated valley. The part about the Germans, though, merely left my counterparts confused, since the valley from which the dragon-believing villager came had never been in a NATO German area of operations. It is unclear how/why the Germans had gotten identified as the jewel/sun thieves.

The senior Pashtun Afghans...marveled at this dragon myth, they remained nonplussed by other less dramatic, but still distinctly, non-Islamic, Pashtun practices/beliefs, such as offerings to the land (as opposed to Islamic sacrifices) by farmers, the "spirits" of mountains and the growing of grapes for wine (allegedly learned from the Greeks) in some isolated valleys. They also believed the (frequently blond) Nuristanis and Pakistani Kalash were both descendants of Alexander's warriors, although of course it has turned out later that was not substantiated by genetics.

John Maynard Keynes was famously shocked when he purchased Isaac Newton’s papers because they were so fixated on the magical and occult. He declared Newton to be the “last of the Babylonians and Sumerians.” But the reality is that there are still Sumerians all around us, in the many enduringly out-of-the-way parts of the world, even some that have historically been crossroads of civilization. They still imagine that there are dragons in the deep, planetary-scale monsters beyond our comprehension and apocalyptic horrors that could end our very existence. While their vast ignorance of the true shape of reality might beggar belief, perhaps it is our own staggering obliviousness about an intricately composed multi-ethnic, factionalized society like theirs that poses the greater existential threat. After all, we alone are equipped to travel en masse to the other side of the globe, to decisively slay a foe and lay waste to his domains, whether he be real or imagined.

On a different note, I just read the New Yorker article on Kahtryn Paige Harden. I was actually surprised to see you pegged as a "conservative" since I had actually not thought of you in strictly political terms until then.

But this anecdote in the article about Harden really struck me:

"When their cohort [from Russell Sage Foundation, I believe] went to see “Hamilton,” the others professed surprise that Harden and Tucker-Drob had enjoyed it, as if their work could be done only by people uncomfortable with an inclusive vision of American history."

If that cohort included researches from the foundation, Is it fair to think that the same kind of narrowness and stereotyping affects their research? It's really bothered to read that.

I take it from their absence in the PCA that no one has looked at Nuristani DNA yet? I'm guessing it's not too different from the nearby Kalasha, despite speaking different Indo-Aryan languages, but we may be surprised.