After the Ice: how foragers and farmers conquered Scandinavia

The placid north’s earliest origins in an age of mud, bloodbath and genocide

Related: Chariots of Ice, Coursers of the Sun, The 100-year-winter and the coming of Ragnarök and Fury out of the North: from pagan slavers to Christian kings.

In 105 BC, an army of 80,000 Romans fell to a barbarian horde led by the Cimbri tribe. The scale of the slaughter left only a few hundred survivors to tell Rome what had happened. This battle was just one defeat in a dozen-year war that raged between 113 and 101 BC. Though the Romans were ultimately victorious under their general Gaius Marius, it was a traumatic near-death experience for the Republic. The Cimbrian War echoed the conflict that the Romans had endured with Gaulish tribes 350 years earlier which had resulted in the first sack of Rome. But more importantly, it anticipated massive migrations that would occur centuries later, with the Roman Empire facing off against a host of Germanic barbarians during what is sometimes called the “Migration Period.”

The Cimbri had something in common with many of the later barbarian tribes that would terrorize the Romans: they were from Scandinavia. In the 300's and 400's, the Goths and Vandals who helped tear down the Western Roman Empire were Scandinavian. Centuries later, during the period between 793 and 1066 AD called the “Viking Age,” young men from what would become Norway, Sweden and Denmark pulled off daring raids for plunder and executed sweeping conquests across a newly Christian Europe. These pagan barbarians exploded out of their cold, austere northern base with such ferocity that clerics assured the terrorized faithful that “heathen” predation signaled God’s judgment upon a sinful people.

To the ancient Greeks, Scandinavia was ultima Thule for its singular remoteness from the rest of Europe. It was presumed to be an island north of Germany, abutting the Arctic Ocean. Unlike the broader continent to the south, Scandinavia had no history of Ice-Age human occupation, the vast ice sheet stretching from Jutland north to the Arctic rendering it uninhabitable even for hardy Pleistocene hunters. The glaciers carved out majestic fjords as a parting gift, and these still haunt Scandinavia’s geology today. The region continues to rebound incrementally upward in elevation at a rate of a centimeter annually as the mantle regains its shape after being weighed down by 10,000-foot thick ice sheets for a cool 100,000 years.

The Greeks and Romans believed that this frigid northern climate was so salubrious as to be an accelerant of Scandinavian fecundity, with fair-haired barbarian clans densely distributed across the north. They held that the northern peninsula was the natural womb of barbarian hordes, ever destined to disgorge bellicose swarms bound for the south. Contemporary historians have repurposed this ancient topos to argue that overpopulation drove the Norse aristocracy’s younger sons abroad, restless Vikings on the hunt for fresh opportunities.

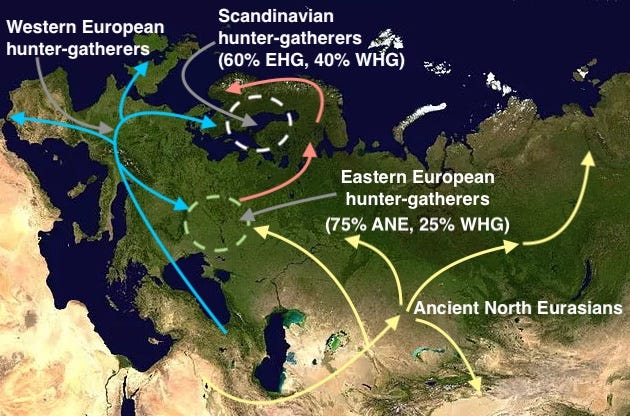

But the tumultuous origins of Europe’s far north reach back far deeper than the Cimbri invasion 2,000 years ago; they date to the clash of disparate bands of stone-weapon-wielding Mesolithic foragers from the east and south 11,000 years ago, the arrival of Anatolian farmers from the south who constructed defensive palisades after millennia of failure to bring agriculture to Scandinavia and finally to the repeated invasions of Indo-European tribes wielding spears, axes and maces. These prehistoric folk wanderings anticipated the restless migrations of the Viking Age when Swedes ranged east and south as far as the Iranian shores of the Caspian Sea, and Norwegians dared to cross the North Atlantic to establish Europe’s first North American bridgeheads.

The audacious and fitful movement of barbarian warlords did not solely bring the Scandinavians to foreign shores; it brought foreigners to Norway’s fjords, Sweden’s Baltic inlets, and Jutland’s windswept pastures. Scandinavians today are the biological descendents of people who pushed the frontier of human habitation to its limit and of a violent migratory vortex that swept in adventurers, refugees and human chattel. Contemporary Westerners might associate the region with public order, cradle-to-grave welfare states, and a penchant for international humanitarianism, but premodern Scandinavia was cold, brutal and harsh. This world was accurately depicted in all its gore, slavery and casual brutality in 2022’s The Northman. The placid peninsula known today for its economy of style, its wealth and its laconic inhabitants emerged miraculously out of some of human history’s most unforgiving bloodbaths, muck and mud.