Africa’s exception to every rule: Ethiopian genetics, sovereignty and religion

Pulling back the curtain on one of Africa’s most enduringly unique nations

The civilized world filed under “BC,” as in all human society stretching back before fifth-century Classical Greece, lies like an impenetrable forest, surely teeming with life, but its details confoundingly obscure. Egyptian hieroglyphs and Babylonian cuneiform put the spotlight on just two civilizations that existed within a vast sea of unrecorded human ferment, our histories constrained to just the few kingdoms and peoples who happened to fall under the light of the proverbial street lamp. The states of the pharaohs and priest-kings offer our lone visible loci around which bustled dense networks of trade, unfurling outward like a net cast into the territories of rich barbarian tribes. But glimmers issue from the darkness; the earliest texts mention otherwise forgotten peoples and lands, lost realities dimly reflected in the annals of an Egyptian pharaoh or the ledgers of a Mesopotamian merchant.

More than 4,500 years ago, hieroglyphs record the land of Yam (Nubia) to Egypt’s south, the tribe of Tjehenu (Libyans) to the west and Retjenu (the Levant) to the east. Only later would the Nubians, Libyans and the people of the Levant speak in their own voices, becoming more than mute extras in the shadow of Egyptian headliners. But literate or not, these people had clearly built complex societies worthy of their venerable neighbor’s notice.

Perhaps most intriguing of these names is that of Punt, which first received a trade mission in 2324 BC during the reign of pharaoh Sahure, and continued to host Egyptian visitors regularly down to the reign of Ramesses III, nearly 1,200 years later. Expeditions ceased as Egypt slid into decline after the 12th century BC, and Punt faded into legend and myth, a byword for legendary wealth and mystery. The most famous expeditions to Punt occurred under the forceful female pharaoh Hatshepshut three centuries before Ramesses III; her missions returned with ivory, myrrh, gold and baboons. Hatshepsut's mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri depicts the voyage of five Egyptian ships to Punt, where they were greeted by a king and queen, Perahu and Ati. Intriguingly, the people of Punt are depicted with red-brown skin, like the Egyptians, rather than the black chosen for Nubians or the yellow for Levantines, suggesting they were seen as a kindred people.

For decades tendentious scholarly disputes simmered about Punt’s actual location. Egyptian texts clearly indicate that Punt lay to their south and east and was reached via the Red Sea, so Yemen, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia were all candidates. The list of goods brought back from Punt included many African items, while genetic testing of baboons Egyptians had mummified (presumably from Punt) narrows the likelihood to the highlands of northeast Ethiopia and Eritrea, neatly in alignment with the largest scholarly faction.

After the collapse of Bronze Age civilization in Europe and the Middle East in the 12th century BC, the total cultural extinction of the Hittites and Mycenaean Greece within decades of each other and Egypt’s simultaneous near dissolution, legations to Punt ended and it faded from Eastern Mediterranean societies’ collective memory. From Punt’s ashes in northeast Ethiopia arose the kingdoms of Dʿmt, and later, Axum. These lands lay at the ancient civilized world’s edge, just beyond the horizon, though familiar enough to the odd well-traveled diplomat or soldier, and to intrepid traders who routinely plied the Red and Arabian seas. Greco-Roman navigators all knew of the port of Adulis, an entrepot into the African interior and transit point to locations further east. The Persian prophet Mani in the 3rd century AD lists Axum as one of the four great civilizations of his day, alongside China, Persia and Rome.

More than 1,300 years after Egypt lost contact with Punt, Axum finally parted those dark curtains, laying the foundation for what would one day become the kingdom of Ethiopia. King Ezana’s early fourth-century AD conversion to Christianity by a Syrian slave named Frumentius initiated a lineage of Ethiopian Orthodoxy that was subordinate in ecclesiastical hierarchy to Egyptian Coptic Orthodoxy for 1,700 years, and fully integrated Axum into the Greco-Roman world. While the language of ancient Egypt is dead, preserved only in the liturgy of Egyptian Christians, the banter in the streets of Addis Ababa likely descends directly from the language of Punt. Here, 2,000 feet higher than Denver’s famous elevation, in 1889 king Menelik II founded a new capital for an ancient empire. A decade later he would lead Ethiopian forces to victory against Italian invaders at the battle of Adwa, earning European powers’ grudging recognition as a full-fledged modern nation-state. This act of defiance against white European colonialism preserved Ethiopia’s status as the sole continuously independent African nation-state, and placed it at the center of early Pan-African imagination; Addis Ababa today is the home of the African Union, as it was of that organization’s predecessor, the Organization of African Unity.

On the one hand, this is fitting, because unlike the northern fringe of African nations that abut the Mediterranean, from Morocco to Egypt, Ethiopia is an undisputed part of Sub-Saharan or black Africa, not MENA (“Middle East and North Africa”). And yet Ethiopia, like its mysterious antecedent Punt, is also a peculiar exemplar for Pan-Africanism; it has long looked north and east as much as it has looked south and west into the heart of the mother continent. Its peculiar ecology, with the Ethiopian highlands entirely above 5,000 feet, has resulted in unique biological and cultural adaptations that set the indigenous peoples apart from their neighbors elsewhere on the continent, while its geographic constraints and conditions have enforced both strong connections to North Africa and to Eurasia thanks especially to the Red Sea.

After the shift of Axum’s political center to the southern highlands in the 7th century upon Islam’s rise, the mountainous terrain served as a natural fortress against invasion and cultural change, though the distance from coastal ports enforced greater isolation. Genetically, culturally and geographically Ethiopia is singular as a synthesis of Sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa and Eurasia, an amalgam that crystallized gradually between Old Kingdom Egypt and Ezana’s 4th-century conversion. The ethnogenesis of this mix of peoples is only now freshly within our grasp, thanks to the tools of genomics, as ancient DNA finally exposes roots buried far beyond the reach of history or archaeology.

The old ones of the mountain

Sometimes you can judge a book by its cover, and you might say Ethiopia’s various ethnicities lie visibly equidistant in physical characteristics from Arabian populations and Sub-Saharan African ones. This includes Semitic-speaking groups like the Amhara, Tigray, Gurage, and Cushitic-speaking ones like Oromo, Somali and Agaw. Not only are many Ethiopians lighter-skinned than other Sub-Saharan Africans, their typically long faces and narrow noses tend to strongly resemble modal Arabian facial features. The Afro-Asiatic languages most Ethiopians speak further reinforce the case for a deep connection to Arabia; the Semitic languages of the region are related to southern Arabia’s indigenous dialects like Mehri in Yemen, as well as extinct languages like the Sabaean spoken by the Biblical Queen of Sheba. And their complexions and what Herotodus termed their “wooly hair” point to Sub-Saharan African heritage as well.

But today, genetic data allows us to move beyond intuitive suppositions. To take a first stab at situating Ethiopians in the landscape of African genetic variation I assembled a dataset of:

10 Bantus from Northeast Africa (I believe these to be Kenyan Kikuyus mostly)

21 Luhya Bantus form Kenya

8 Bantus from South Africa (likely Zulu)

19 Druze Arabs from Lebanon

12 Egyptian Muslims

43 Esan from Nigeria

7 Ethiopian Amhara

7 Ethiopian Oromo

5 Ethiopian Tigray

12 Ethiopian Jews

19 Iranians

54 Yemenis

15 Yemeni Jews

Pruning the marker set down to shared SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) present in all individuals gives us 120,000 SNPs, plenty to run principal component analysis (PCA) and admixture analysis. The former method takes the genetic variation of the individuals and models it as a multidimensional space of which we then represent the two most explanatorydimensions on a graph. An admixture analysis meanwhile assesses individual genetic variation and how it fits into a model of population history given specific variables. The model defines a K number of populations, and each individual genotype gets fitted to a specific ratio of contribution from each of these populations.

The plot of PC 1 against PC 2 for the two foremost dimensions of variation in the data illustrates the stark differentiation of Eurasian and African populations along PC 1. This axis of variation explains ten times as much variation as PC 2, which differentiates Ethiopians from literally all other human populations. The fact that there is an Ethiopian/non-Ethiopian axis nevertheless indicates something unique in the genetics of Ethiopian peoples. If Ethiopians were a mixture of Bantu or West African populations with Eurasians, we would expect them to be positioned exactly in the middle, in order of individual admixture fraction. And we see variation in distance to Eurasians; the Semitic-speaking populations are clearly closer to them than are the Omoro, the world’s largest Cushitic-speaking group.

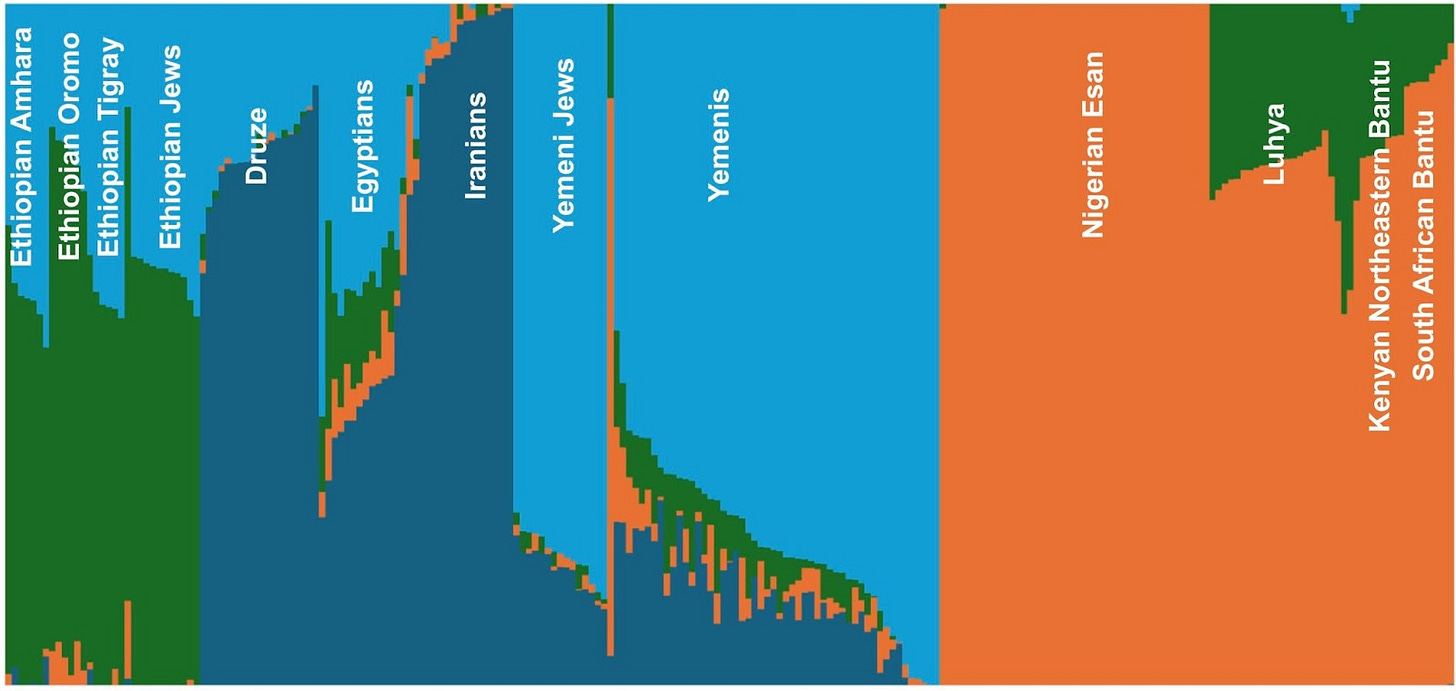

In the bar plot above, each slender vertical line represents one of the 232 individuals’ genotypes, with the proportional ancestral components stacked vertically, assuming a set of diverged populations, K. I ran the dataset above in an unsupervised mode with K = 4, meaning essentially that I did not price in any prior fixed population information, but just asked the model to assess each individual as a combination of up to four hypothetical component populations that in combination would have to account for all ancestry in the 232 samples. What you immediately see is that some groups are most parsimoniously modeled as descending from just one ancestral population. The Nigerian-identified samples are all entirely orange, while the Bantu groups are predominantly so. This affinity from west to east Africa reflects the Bantu expansion out of Cameroon starting 4,000 years ago that homogenized the continent’s prior genetic variation from the Bight of Benin down to the Cape of Good Hope. Within Ethiopian samples, this component is most prevalent in the Oromo, which makes geographical sense since the Oromo lands sprawl across the country’s south and east, and thus interface with both Sudanese Nilo-Saharan speakers and Kenyan Bantu speakers.

The PCA has already confirmed that Ethiopians carry Eurasian ancestry, as suggested in some of their typical features, and happily the admixture results concur. The light-blue cluster is maximized in Yemenis and Jewish Yemenis, and seems to reflect Arabian heritage, while the deep teal-blue cluster shows up more in populations to the north and east. While Egyptians are split between these two Eurasian clusters, the Ethiopian populations’ ancestry from Eurasians appears almost exclusively in the form of the light blue cluster most common in Yemenis. This accords with the PCA as well, where Yemenis and Yemeni Jews are both shifted towards Ethiopians compared to Iranians or Druze. In alignment with the PCA, where Semitic ethnicities are shifted toward Eurasians, they have substantially more Arabian-like ancestry than the Cushitic-speaking Oromo.