A Nile shadow 4,500 years long

2500 BC genome closes old case, poses new questions about prehistory

For billions of years, life’s replenishment has proceeded with a certain leaden regularity. Genetic code is incessantly copied (nearly) verbatim, line by line, word for word, letter for letter. Lineages might be unceremoniously snuffed out, and cataclysms might coldly erase millennia of progress, of evolution, of adaptation. But those are private tragedies, superficial outcomes. Across the eons, across the vast kingdoms of life, the mechanisms fine-tuned to roll out generation upon generation of progeny trundle on, unmoved by fad or fashion. In the animal kingdom, sexual reproduction regularly reshuffles a given species’ extant set of options and mutation occasionally injects a genuine wild card capable of shaking up a whole stolid lineage.

But the mechanism itself? It chugs along unchanged and unchangeable, a wonder of clockwork reliability. Universal and eternal. DNA across the vast plant and animal kingdoms is predictably recombined, transcribed and read according to one basic set of procedures. And it matters not whether the particular copy of a genome comes tidily packed in the seed of a just picked apple, whether it has spent a century and a half bobbing along deep in the ovary of sea turtle, or whether it was just produced Sunday afternoon in a man snoring on his sofa. Or, for that matter, in an ankylosaurus who died 67 million years ago. DNA is DNA. This level of life knows no version of humanity’s Tower of Babel. Darwin’s “endless forms most beautiful” chart infinite different life courses, but the secret of their operating instructions has only ever been breathed in one simple four-letter code.

In this, the natural world could hardly be less like the manmade products of our restlessly mimetic species, with our protean languages and dialects that morph daily, our unchecked appetites for borrowing, neologisms and our constantly evolving script conventions. Languages blink out of existence incessantly, and robust language families can chart splits on the scale of centuries, with the Middle English of the Middle Ages scarcely decipherable to English speakers today. Little wonder then that we require a stroke of luck like rediscovering the trilingual Rosetta stone to even begin to decrypt entire long-ago languages, no matter how copiously they might be preserved. And to this day, all too often whole bodies of indelibly inscribed language remain as mute prisoners staring back at us, in plain sight, but utterly incomprehensible, like the Minoans’ Cretan hieroglyphics or Linear A.

In science’s most recent generations of frenetic activity and progress, some of the keenest minds of our species have been proceeding stepwise towards a complete grasp of this universal code. Between identifying DNA’s double-helix structure in 1953 and now routinely reading out entire genomes letter for letter, they have come at it from every angle, the intervening decades marked by countless small steps and great leaps forward in our understanding. In this century the field has both converged on methods to extract DNA from ever more ancient samples and continued refining methods to read out billions upon billions of base pairs.

Compared to ancient inscriptions carved in stone, ancient DNA is fiendishly hard to recover. But once extracted, with today’s technologies, it has the power to spill untold secrets. The genome of a single anonymous Egyptian man who lived and died some 5,000 years ago plainly shows us how genetically like their storied Old Kingdom ancestors Egyptian citizens remain today. And just as discerning his same ancestral mix in contemporary Egyptians reveals millennia of continuity along the Nile, decomposing his genetic makeup also sheds light back millennia before his lifetime. Unraveling his ancestry composition yields clues about the peoples of prehistory who made ancient Egypt what it was at its height. And all it took was a single human genome. That and the clarity of a changeless code transmitted in just four symbols since time immemorial.

In the West’s self-conception, Egypt plays a special role, the root of the tree that eventually became civilization, spreading north to Europe, and eventually westward. To the ancient Greeks, Egypt was the font of ultimate knowledge, a world already aged even in antiquity, a fossil from a bygone time as the Greeks were rising in the middle of the first millennium before Christ. It is a miracle that we know so much about the Egypt of cities, temples and pyramids that arose along the Nile so long ago, but this is as the Egyptians themselves intended; they left an impact out of all proportion to their population. Hundreds of generations later, we see and read their works in stone across the landscape and at their still-standing monuments. Narmer, the first ruler of a united Egypt, lived 2,750 years before Plato; the same vast span of time separating us from Rome’s 753 BC founding today. About four centuries after this first historical pharaoh, Egypt’s Old Kingdom was born in 2686 BC, marking the beginning of the dynastic cycle that defines later Egyptian civilization. This early period, when copper was more common than bronze, set the foundation of the polity that the Persians would eventually conquer a final time in 343 BC, 2,343 years later, concluding the long chapter of Egyptian independence. But the shadow of Egyptian culture persisted far longer than the last native pharaohs. The religion first institutionalized in the Old Kingdom continued down to 537 AD, when Justinian the Great ordered the great temple complex at Philae closed. The indigenous Egyptian language persisted even longer. Coptic, its modern descendant, remained a living language in isolated pockets of Upper Egypt into the 20th century, and is still the ritual language of over ten million Coptic Orthodox Christians today.

The fact that the Egyptian people live on today millennia after their Sumerian contemporaries in Mesopotamia were but faint memories is a key reason their ancestors remain so vivid to us today, not flat sketches in history books. Even now we know Imhotep’s name and the lineaments of his life as a vizier, priest, architect and scribe. Born in 2670 BC, he was instrumental in the design and building of Djoser’s step pyramid. He is arguably the first historically attested professional whose name and biographical details we have in the entire history of the human race.

The lucky fact of such troves of ancient Egyptians’ writing being preserved in imperishable stone inscriptions in an arid climate furthers our extensive knowledge of ancient Egypt. These records tell us that the Egyptians created an incredibly robust culture, maintaining continuity down to the Greco-Roman period. Even under Roman rule in Egypt, Imhotep remained a worshipped culture hero; and what’s more, if the ancient architect had time-traveled to Augustus’ time, he would have found the Egypt of that day easily comprehensible. This continuity delivered the key that unlocks direct access to the Egyptian past for us so far into the future. Hieroglyphics, Demotic (a late form of Egyptian script), and Greek were the languages inscribed on the famous Rosetta Stone, a Ptolemaic-era tablet inscription dating to 196 BC. For commoners, Egypt, though then ruled by the Macedonian Ptolemies, remained little changed from the nation that had built the pyramids 2,500 years prior. So it was necessary to set proclamations in the language and script of the country’s majority, as well as that of their Greek-speaking rulers. Two thousand years later, 19th-century scholars, whose Christian culture stemmed directly from the Greeks’, could decrypt the hieroglyphs via this classical inheritance.

Through archaeology and history, ancient Egypt remains vivid in the present; its symbols and monuments exert a magnetic attraction even in a distracted age of smartphones and self-driving cars. But what about the people? Today, Egypt is the world’s most populous Arabic-speaking nation. Until the petro-dollar fueled rise of the Gulf Arabs in the late 20th century, for most of the past eight centuries since Baghdad fell to the Mongols, Egypt had been the cultural nerve center of Arabic literature and Sunni Islamic orthodoxy. Imhotep may have been able to make himself understood to Egyptian peasants in 500 AD, and even recognized the rituals and deities in rural shrines and temples of Late Antiquity, more than 3,000 years after his death. But within a century of Rome’s fall, the native religion would have almost fully vanished, and in another five, after 1100 AD, the Egyptian language would be mostly replaced by Arabic. Memes are not as stubborn as genes. Just as a people can accept Islam, so can they abandon their old languages for the new.

Ancient DNA allows us to examine exactly how continuous a people are with their forebears, but the way ancient Egyptians preserved their elites’ remains with chemical processes has left paleogenetics a relative dearth of material. Ironically, the very mummification that brings us so eerily close to the human faces of antiquity, guarantees their DNA’s destruction. Nevertheless, a 2017 paper reported genome-wide data on three ancient Egyptians, with the authors finding substantial continuity between ancient and modern Egyptians. After their conquest by Arab tribes Egyptians were subsequently Islamicized and Arabicized, but their genetic origins remained predominantly among the native peasantry. However, a major lacuna in this work is that the oldest whole genomes (as opposed to just mtDNA) date to the 8th century BC, after the New Kingdom’s fall, at the very end of dynastic Egypt proper. Though this was still the Egypt of the pharaohs, these last centuries of native rule marked a great civilization’s twilight, and outside influences, from Libya in the west, Nubia to the south, as well as the Levant and Iran, loomed large.

Now, a Nature paper reports the analysis of an entire genome from the Old Kingdom, approximately 1,850 years before those previous oldest genome-wide samples in our data. Going back to the very root and foundation of Egyptian civilization, this individual gives us a clear window onto Egypt’s genetic and demographic landscape at the very beginning of history.

The man from the dawn of Egypt

The new sample was recently recovered from the remains of a man who died at Nuwayrat, some 150 miles south of Cairo. Using carbon-dating, the 95.4% confidence interval puts the individual’s death between 2855 and 2570 BC and the authors favor the recent end of that span. Though the paper has the Old Kingdom in its title, it is quite possible that a Nuwayrat man died during the last decades of the early-dynastic era, which ended in 2686 BC, but again, the authors seem to lean toward the tail end of the distribution. The shift that differentiates the Old Kingdom from the early-dynastic period is subtle, rather than something culturally or politically abrupt, more a matter of chronological convenience than substance. The creation of large-scale stone-construction pyramids that so defines the Old Kingdom in our imagination reflected a newly solidified state capacity, but hieroglyphs, divine rulers, and distinctive Egyptian artistic styles all were already commonplace in the preceding early-dynastic period. The difference then is more of degree than quality, and the transition is to a great extent a matter of retrospective semantics. For all practical purposes, it is irrelevant whether the Nuwayrat individual died in the last decades of the early-dynastic period, or the first century of the Old Kingdom.

His burial in a large pottery vessel within a rock-cut tomb suggests a high social status for that period. The man was likely about 60 when he died, and had heavily worn teeth and age-related osteoarthritis. Though the burial indicated elite status by the end of his days, his skeletal remains also reflected a high level of stress from hard labor throughout his life. The particular patterns of stress and wear on his bones are consistent with the possibility that he was a potter. Isotope analysis of dental enamel and collagen point to an omnivorous diet, with the plant component being wheat and barley. The chemical signatures are also consistent with growing up in a hot, dry climate. All of this bolsters the case that the man buried at Nuwayrat was a native Egyptian of his time, albeit one who enjoyed some upward social mobility later in life.

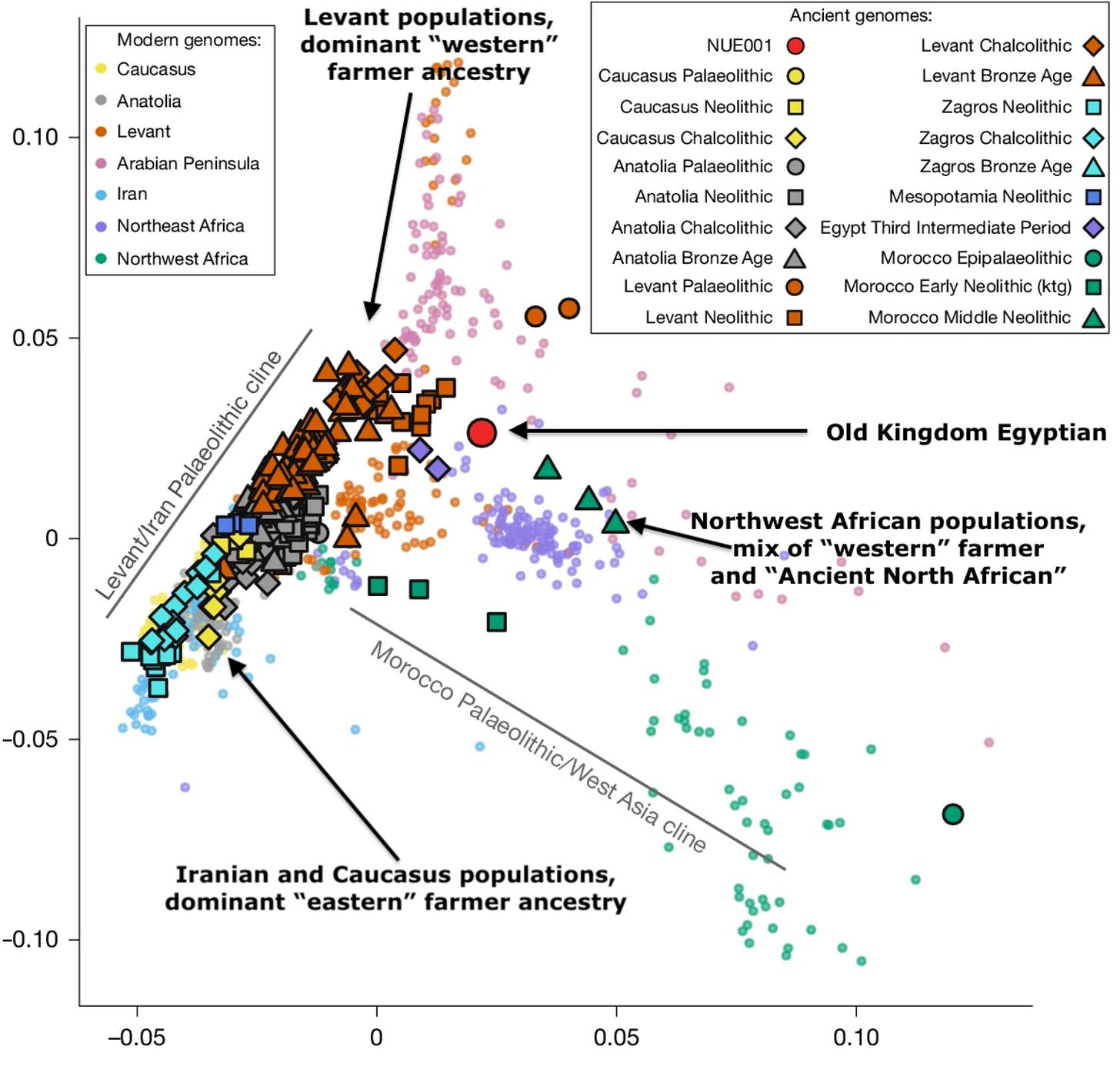

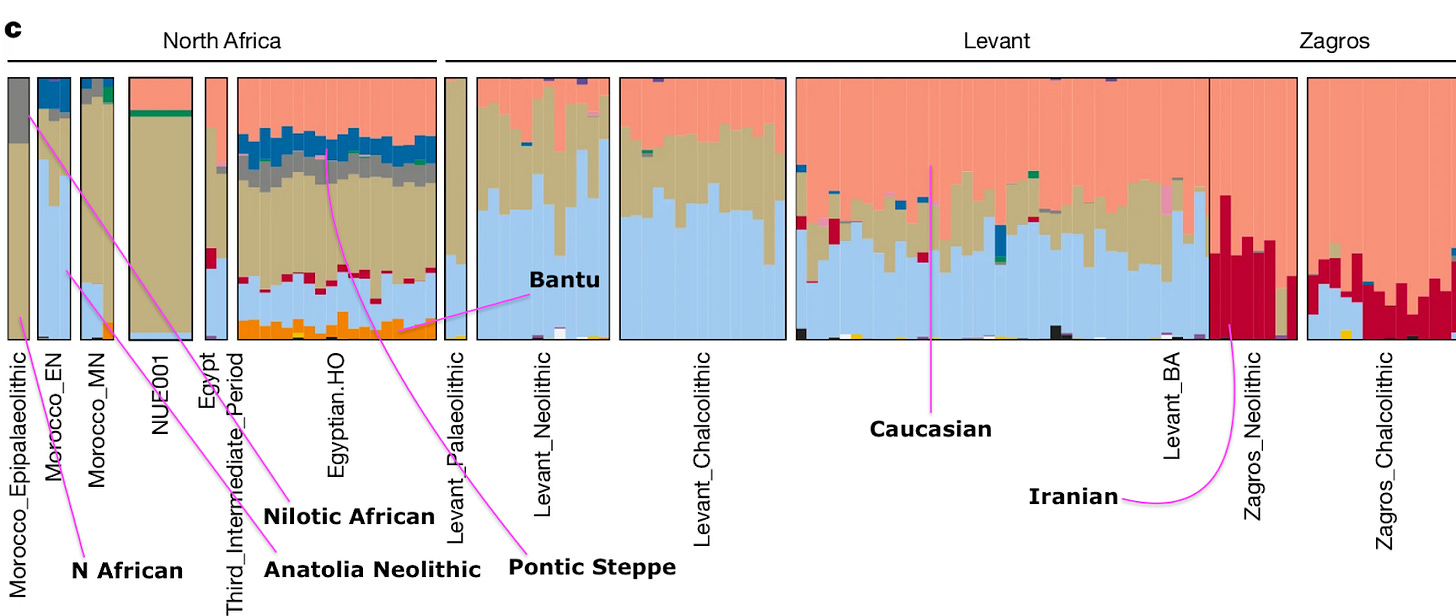

For labeling purposes in the analysis, the researchers called the genome NUE001, and sequenced it to 2.02× coverage. This means they read and recorded any given position on Nuwayrat man’s whole genome about twice. Not sufficient if Nuwayrat man needed medical diagnosis, but a good start for population genomic analyses. Researchers compared Nuwayrat man to thousands of modern and ancient genomes, using anywhere between 71,202 and 593,124 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), depending on the type of analysis. This number of markers is more than sufficient for both principal component analysis (PCA), which maps individuals along independent dimensions correlating with genetic variation, and for admixture-modeling, which breaks down individual genomes into discrete ancestry components.

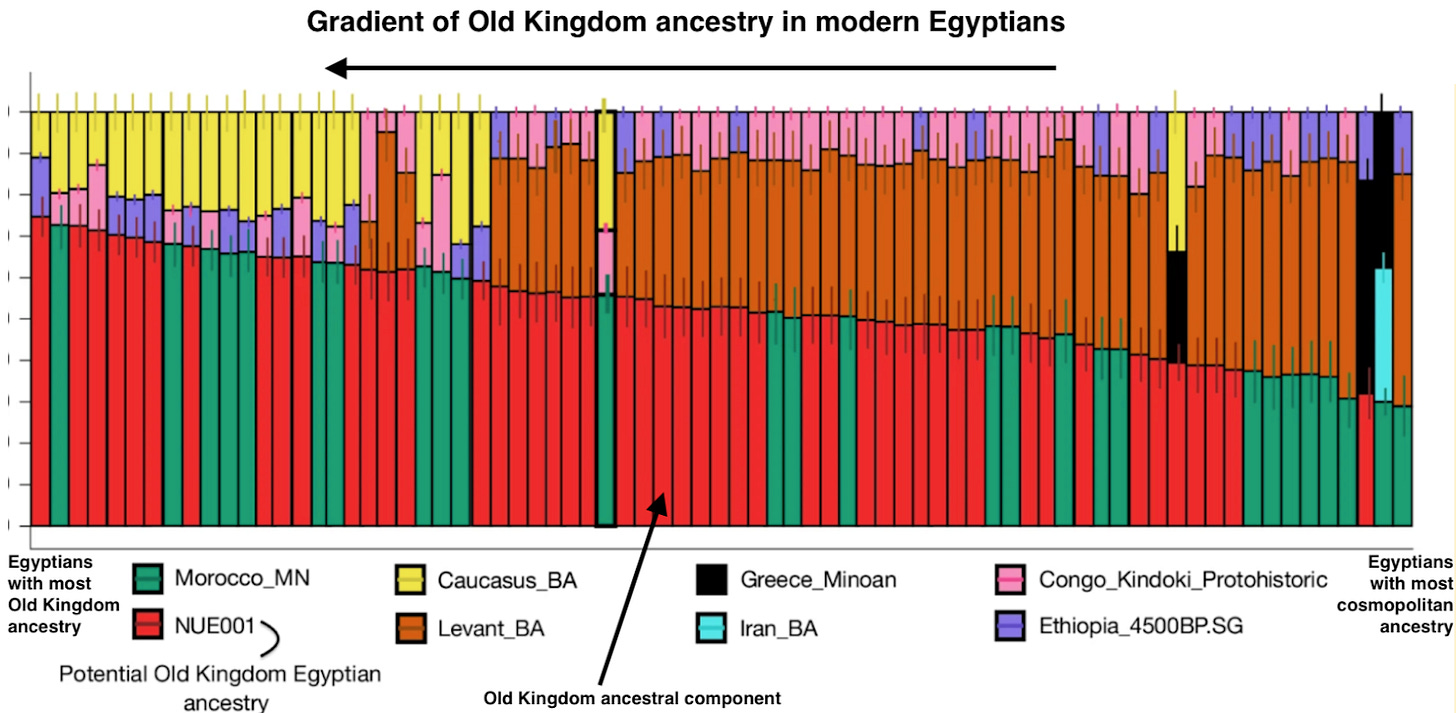

The PCA and admixture analyses indicate that NUE001 had parents with predominantly North African ancestry, and minority ties to West Asia, specifically the Caucasus and Iran. Interestingly, a shift occurred millennia later during the period of the New Kingdom; even before the Roman conquest, Egyptians seem to have seen an influx of particularly Levantine ancestry during the early to middle Bronze Age, long after the Nuwayrat man’s death. Finally, note how the modern Egyptian samples from the “Human Origins” (HO) dataset reveal continued predominance of the khaki-toned North African cluster, but at reduced levels compared to antiquity. Modern Egyptians have Sub-Saharan African ancestry, both Nilotic ancestry, with a presumably Nubian provenance, and Bantu-like heritage reflecting the wide reach of the Islamic slave trade. Pontic-steppe genetic influx is also present, likely from Mameluke slaves who were imported from among the Turkic peoples north of the Black Sea.

The PCA plot above aligns with the admixture analysis. NUE001 is near the North African cluster, but shifted toward ancient Levantines. The purple points representing modern Egyptians are even further shifted, yet still nearby. It is notable here that Arabians and modern Levantines remain distinct from modern Egyptians, refuting the notion that Arabic-speaking Egyptian Muslims descended from newcomers from the east, with the Copts being the only indigenes.

To get clarity on the proportion of Old Kingdom Egyptian ancestry remaining in modern Egyptians the authors used a more explicit and formal method that modeled NUE001 as a hypothetical donor population, along with a slate of other groups derived from ancient DNA samples (reading left to right, Morocco Middle Neolithic, Bronze Age Caucasus, Minoan Greece, early Bantu-era Congo, Nuwayrat man as NUE001, Bronze Age Levant, Bronze Age Iran and prehistoric Ethiopia). It is quite plausible that the Morocco Middle Neolithic component is simply ancient Egyptian ancestry being mis-categorized because Nuwayrat man was himself mostly North African. Assuming that the Moroccan Middle Neolithic is also tagging in ancient ancestry from the Old Kingdom, modern Egyptians average a bit more than half ancient Egyptian. Because Sub-Saharan African ancestry is so easily detected given its immense internal diversity and distinctiveness, we have already known for a couple of decades that about 10-15% of modern Egyptian ancestry derives from the Islamic-era slave trade. But that still leaves a substantial minority, which seems to be the product of gene flow out of West Asia probably occurring in waves between the Bronze Age, about 4,000 years ago, until after the Arab invasions of the 7th century AD. Finally, the number of individuals showing Caucasian ancestry tracks the southbound trade in military slaves that persisted for 500 years along routes through the Black Sea. Between AD 1300 and 1800, Egypt’s ruling elite were Mamelukes, who were usually ethnically Turkic or Circassian (and remain overrepresented among the nation’s ruling class, though they are now fully Arabized).