A language family of one, a land beyond conquest

What a Basque genetic plot twist tells us about prehistoric Europe

It is a truth universally acknowledged that Basques are weird Europeans. The unique and isolated group’s rugged domains stretch between today’s northern Spain and southwest France, hugging an out-of-the-way curve of coastline hard against the Atlantic. But their strangeness goes far beyond geography; that much was already clear in the early 20th century when scholars investigating the past were limited to far more primitive tools. For one thing, linguists had long since recognized that the Basque language, Euskara, was not a Romance language like everything else spoken in Iberia and France (with the single curious exception of Breton, which arrived in the 400’s to Gaul’s far northwestern peninsula from British Cornwall). Furthermore, by the 1950’s, human geneticists working with blood groups had determined that the Basque people had the world's highest RH-negative frequency, at 30%. This reality explains pre-modern observations of exceptionally high Basque miscarriage rates due to the fetal risks inherent in every subsequent RH-positive gestation after the first delivery to an RH-negative mother (Medieval Christian observers attributed the miscarriages to the malevolent influence of the devil, as would befit a clannish people so resistant to the church's conversion efforts).

Today we know that the Basque language is in fact the only indigenous non-Indo-European language to still survive from antiquity (also-rans Paleo-Sardinian and Etruscan endured until around 500 AD and 100 AD respectively). Its handful of fellow non-Indo-European languages spoken across Europe today are all comparatively recent arrivals: Finnish and Estonian arrived 2,500 years ago, Hungarian 1,000 years ago and Turkish 500 years ago. The Romans encountered the Basques’ ancestors when their legions arrived in northern Spain in the 1st century BC, and it is clear from Basque-like given names that those people spoke a language ancestral to Euskara. Their language was and is a linguistic isolate, with no known relatives spoken elsewhere, now or in the past. This means that the Basques’ nearest neighbors’ languages share more with say Farsi in Iran, Ossettian in the Caucasus or even my parents’ Bengali some 8000 kilometers away than with the impenetrable Euskara of the shepherds on nearby hillsides. This linguistic curiosity in and of itself already warranted investigation and made this society tucked into the corner of the Bay of Biscay something of a puzzle.

But biology added another layer to the Basque mystique and mystery. For much of the 20th century, blood-group distributions were early molecular geneticists’ major way to investigate population-scale relationships. Blood-type inheritance followed a classically Mendelian model, and antigen testing was simple and already an essential tool for transfusions. And here again the Basques stood out as exceptional; most populations harbor an RH-negative rate below 10%, the Basques’ was 30%. Archaeologists, historians and classicists widely concluded from these facts that the Basques were probably the first Europeans, a remnant people from a world before the Indo-Europeans. This was the most parsimonious explanation for their linguistic and genetic outlier status as far as we could then delve into it.

About four decades ago new genetic markers finally came online to propel us far beyond the provisional insights already gleaned from simple ABO and RH blood groups: Y (men’s direct paternal line) and mtDNA lineages (the direct maternal pedigree of men and women both). Y and mtDNA analysis from the late 1980’s to the mid-1990’s established that modern human lineages coalesced back to a common ancestor between 100,000 and 200,000 years ago in Africa, “mitochondrial Eve” and “Y-chromosomal Adam.” But the fine details of these lineages answered more than just deep evolutionary questions about human origins: they could also be used to relate populations to each other in the present day. For example, in the late 1990’s geneticists noticed that most Jewish men with the surname Cohen, which is passed patrilineally and who are reputedly descended from Moses’ brother Aaron, indeed shared one Y-chromosomal lineage that seems to trace back to a man who lived some 3,000 years ago.

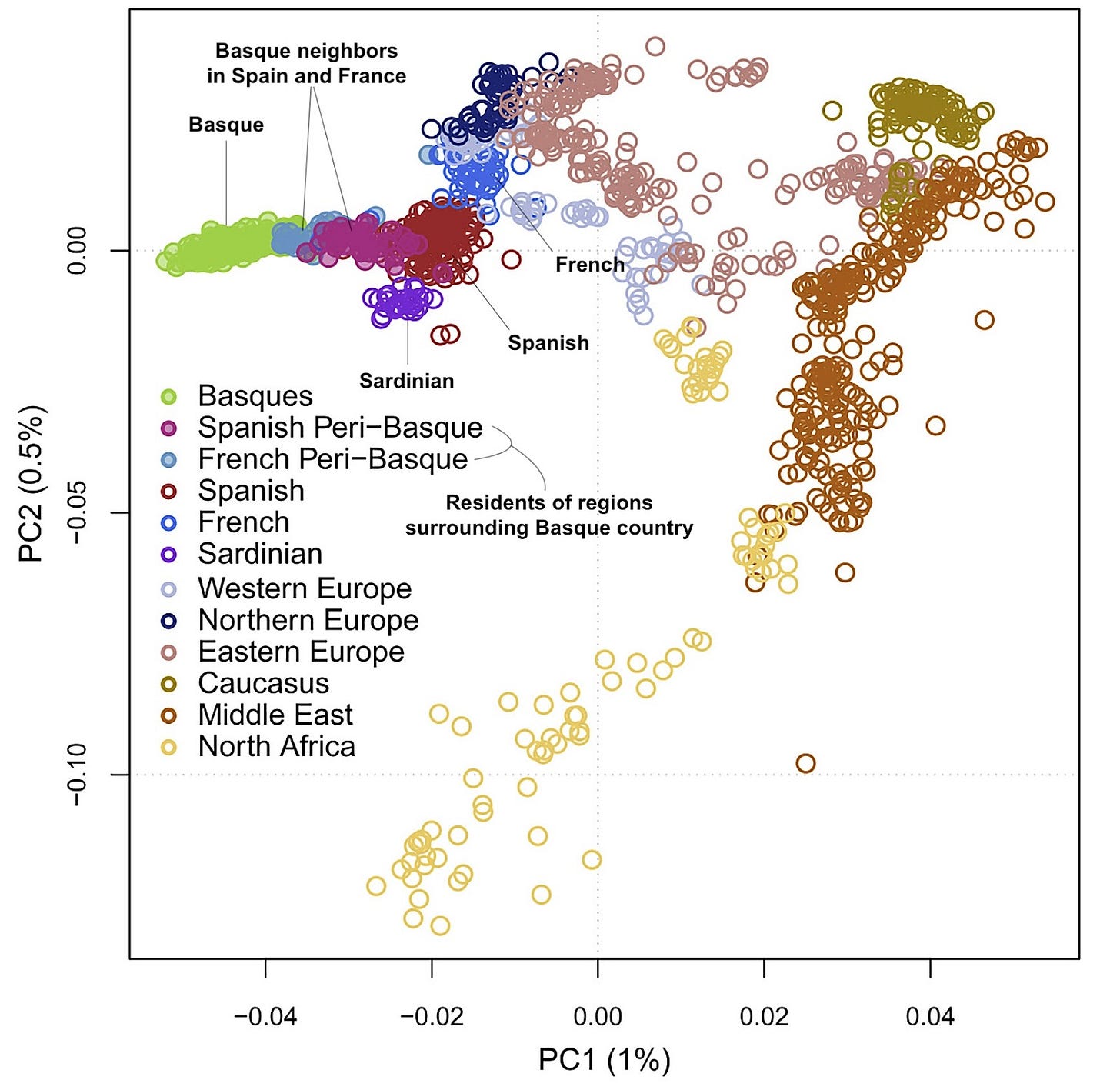

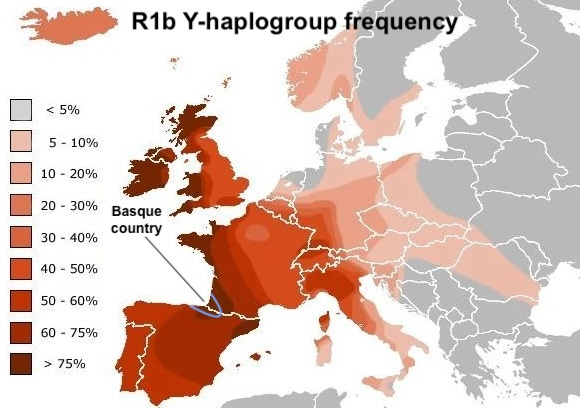

Questions of Jewish genetics were often profitably addressed by Y and mtDNA analysis because these markers could be cross-referenced with historical records. Obviously this is irrelevant for prehistoric Europe, with its dearth of texts. Nonetheless, geneticists noticed that the Basques stood apart on maps of Y-chromosomes and of mtDNA for being maximal for both the Y lineage R1b (85% of Basque probands) and the mtDNA lineage U5 (20% of Basque probands). Outside Southern Europe and particularly the Basque country, U5 is common only in Europe’s far north, while R1b sees a wide distribution across the Atlantic coast, and reaches its highest frequencies in the Basque country and the Celtic fringe (both approaching 85%). Two decades ago, when this was being established, debate was lively over whether Europeans descended predominantly from Neolithic farmers who migrated out of the Middle East or from Ice-Age foragers. The distributions of both R1b and U5, far from agriculture’s Middle Eastern point of origin, suggested to researchers that both were associated with the earlier Ice-Age foragers, and the high frequency of both in the Basques seemed to be an independent confirmation, given the group’s attested genetic and linguistic uniqueness.

So, might the Basques be descended from Ice-Age foragers, with the Basque tongue being a remnant of Europe’s Pleistocene-era dialects? With ancient DNA analysis’ advent in the last fifteen years the answer is: probably not. The Basques are in fact probably descended from Europe’s penultimate people, not its first nations.

A story of the first farmers

In 1991, two passing German hikers discovered the miraculously intact remains of Ötzi the Iceman at 10,000 feet elevation in the Alps. Authorities initially thought the remains were of a recently deceased hiker, but the medical examiner immediately recognized Ötzi’s complement of tools as Neolithic. Later forensic analysis showed that he had died high in those mountains around 3300 BC (a significant stroke of luck for science, the elevation contributing to his incredibly well-preserved state), apparently at the hands of violent assailants. He was first struck by arrows, after which he seems to have fallen, allowing those tracking him to catch up. Finally, he futilely attempted to fend off his attackers in hand to hand combat, in the end succumbing to his wounds. Initially, anthropologists focused on his bones, teeth and even the remnants of food in his gut.

But eventually genetic science advanced far enough, from more effective extraction to efficient typing and sequencing, for us to delve into his DNA. Scientists accomplished the sequencing of his whole genome two decades after his discovery, some 5,300 years after he died. One of the first Neolithic Europeans whose genetic results we could examine, Ötzi confounded scientists’ expectations; he did not cluster genetically with any northern Italian populations (nearest whose home regions he had died), or even any peninsular Italians generally, but rather with island Sardinians. The import of this unexpected result was still hard to parse in 2012, but today we benefit from a vastly more intimate understanding of Europe’s past 10 millennia of demographic turnover. The reason Ötzi hews genetically closest to modern Sardinians is that among all European populations, Sardinians retain the greatest proportion of Neolithic-farmer derived ancestry, an input that ultimately derives from agriculturalist populations expanding en masse out of Anatolia. To a first approximation, modern Europeans can be conceptualized as a mixture in various ratios of three populations, 1.) indigenous foragers we label Western Hunter Gatherers (WHG) who were already present in Europe as the last Ice Age was ending 11,700 years ago) 2.) Anatolian farmers who arrived in Europe by first crossing the Aegean to Greece around 7000 BC, and 3.) nomadic herders who after 3000 BC pushed in from the Pontic steppe to the North European plain south of the Baltic.

Ötzi is genetically different from almost all modern Europeans in that he harbors not a trace of steppe-herder ancestry. The reason is simple: aside from a few early pioneers based in the pastures of the lower Danube, steppe pastoralists did not begin to penetrate Europe until after 3000 BC, a few crucial centuries after the Iceman’s lifetime. Instead, Ötzi’s genome is solely a combination of Anatolian agriculturalist and WHG. Over the 2010’s, geneticists sequenced copious samples from all three populations, in the process settling a number of long-standing open questions.