A Hun by any other name

On the genetic trail of Europe’s enduring bête noire

The Epic of Gilgamesh ends with the intimation that immortality can only be achieved through everlasting fame, or as the case may be, infamy. Percy Shelley’s 19th-century poem Ozymandias reflects this truth, as the ancient king of kings bellows “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”, spared the foresight that his legacy would one day be enumerated in forgotten, decaying monuments. In ancient Greece, Ozymandias was the name for Ramesses the Great, the most powerful Pharaoh of Egypt’s New Kingdom. Today, despite his achievements, he is a vague and obscure name, dimly recalled.

Names and memories decay in history’s winds, as surely as works of stone blasted by desert sandstorms, but a select few can be powerful enough to evoke strong emotions after thousands of years if nurtured and revived. When in the mid-19th-century Europeans became involved in geopolitical machinations in Central Asia and China, they resurrected a deep cultural memory and with it the fear of a violent menace from the east in the form of the Huns, nomadic warriors who had been defeated 1,400 years earlier, decades before Rome fell.

The specter of these pitiless barbarians swooping in on horseback had haunted the ancients, their horror recorded in histories that filtered down to modern Europeans. In these classical texts, the Huns were the epitome of brutal and alien savages whose raison d’etre was total victory on the battlefield, punctuated by gluttonous orgies of flesh, food and drink. They were the embodiment of the European cultural imagination’s bête noire, the austere and erudite Roman aristocrat contrasting sharply with the brutish barbarian guzzling mare’s milk and gnawing on a hunk of raw meat while in the saddle.

And yet despite this reputation and their enduring impact on the collective memory of Europeans, the Huns were an active menacing presence in Europe for less than a century, their reign of terror exploding with a scalding burst and then dissipating over the centuries like a dense morning fog burning off. Their wide-ranging raids that ravaged the continent were checked by a signal defeat in 451 AD at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains near modern Troyes, France, and hopes for a lasting empire expired with Attila’s death in 453 AD. Without a charismatic leader, and with their aura of invincibility deflated by a Roman victory, the Hun Empire was soon torn apart by rebellions. Nomad empires run hot and burn out fast; upon defeat, fierce clans easily united in victory swiftly turn fractious, repudiating leaders who can’t deliver a triumph.

The Huns left their stamp on Western cultural memory because they were the first mounted archers to bring the full force of steppe nomadic military skill to the very heart of the ancient world, with Atilla invading Italy itself. They perfected a martial way of life pioneered by the Scythians and Sarmatians, Iranian-speaking peoples who fought and defeated (before being defeated by) the Greeks and Romans. But it was the Huns who took the ethos of the predatory nomad to its reductio ad absurdum. The Huns were wealthy in horse and sheep, but they understood true riches came from plundering the settled peoples, who dwarfed them in numbers, but were like lambs to slaughter in the face of well-armed, mobile hordes.

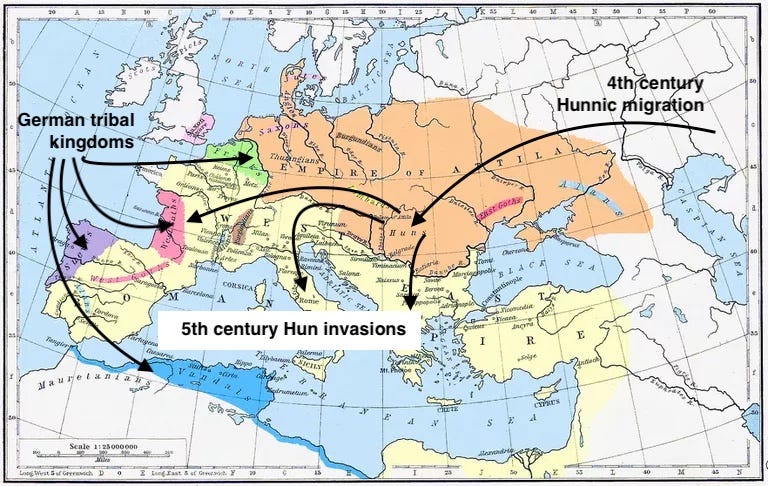

Though the Huns reached the borders of the Roman Empire only in 395 AD, their impact was already felt a generation earlier. It was they who caused the Völkerwanderung, the migration of peoples, that roiled the fifth-century Roman world and contributed to the old order’s collapse by century’s end. The Huns did not finish Rome, but they set in motion the forces that would eventually topple its dominion. It was the Huns who drove the Goths, Vandals and Alans west, all nations that would swoop down on Roman provinces like ravenous predatory birds. They were to dismember the Empire and feed upon its decaying carcass after its fall. They did not see the completion of the havoc they wrought, but the Huns were the boulder dropped in a placid lake whose inexorable sequence of destructive waves coursing out from Eurasia’s core would eventually slay their Roman rival.

We know the Huns introduced a new style of warfare and summoned a fearfully otherworldly aspect to European witnesses because their victims recalled vividly their frenzied terror. The 6th-century historian Jordanes, a Roman of Gothic descent, writes of the Huns’ entrance upon the Pontic steppe two centuries earlier:

…by the terror of their features they inspired great fear…They made their foes flee in horror because their swarthy aspect was fearful, and they had, if I may call it so, a sort of shapeless lump, not a head, with pin-holes rather than eyes. Their hardihood is evident in their wild appearance…they grow old beardless and their young men are without comeliness, because a face furrowed by the sword spoils by its scars the natural beauty of a beard. They are short in stature, quick in bodily movement, alert horsemen, broad-shouldered, ready in the use of bow and arrow, and have firm-set necks which are ever erect in pride. Though they live in the form of men, they have the cruelty of wild beasts.

Even the Goths, a highly militarized people, found the Huns to be inexplicably cruel, without pity or conventional human fellow-feeling. The late Roman elites were already Christian, so Attila to them was the “scourge of God,” and the Huns were seen as forces of nature, instruments of an angry God, fated to mete out punishment to the wicked who had sinned against the Almighty. The Huns became bogeymen to scare children, and their very name could strike fear in the hearts of their enemies.

But readily lost in their mythic import and their singular cultural influence is that the arrival of the Huns to the civilized world foreshadowed what was to come; they were the first chapter in a longer, darker saga. The structural forces of Eurasian warfare were evolving and mutating as Rome entered its late period, fatefully complacent thanks to its track record of repelling earlier barbarians, from the Germanic Cimbri and Alemanni to the Iranian Sarmatians. But the millennium after Atilla’s death in 453 AD would be defined by the ascendancy of mounted warriors from one end of the Eurasian supercontinent to the other. It saw the appearance of heavily armored knights in Europe and the rise of the samurai in the Japanese islands. But more importantly, these were the centuries when vast nomad hordes, Turks and Mongols, prowled the empty Eurasian heartland between the outposts of the civilized world. Waves of these nomads repeatedly conquered and transformed the venerable empire and city-states that ringed the heartland’s periphery. Even after the Huns faded from history, the specter of the nomad did not disappear. The Magyars stormed across Europe, the Turks came to rule Iran and India, and finally, the Mongols burst onto the scene like a thermonuclear bomb, rolling west to the Mediterranean and sweeping east to the Pacific in a series of unparalleled conquests that came to encompass the whole continent. The Huns as a people faded, but the Huns as an idea haunted Eurasia for a millennium.

The First Nomads of the Eastern Steppe

The story of these fearsome warriors of the steppe that wreaked so much havoc between the 5th and 15th centuries AD actually begins in the Far East long before Atilla, more than 2,000 years ago. Attila's empire was actually one of those rarities, a sequel that topped the original, the New Testament to the Old. Scholars have now assembled a mass of circumstantial evidence pointing to the fact that the Huns that bedeviled the Romans were actually descended from the Xiongnu Confederacy that had harried and menaced Han-dynasty China six centuries prior.